Since prehistoric times, when shells, stones and bones were used as personal decoration, jewelry has been more than just a mark of status or rank. It was also worn as protection from the dangers of life.

The pendant rings that hang from these hollow gold earrings are thought...

Pleasant scents held a more mythical significance than they do today. In many ancient cultures it was believed that burning incense was a way to connect directly with the gods. So the earliest aromatic jewelry would have packed a double punch: it was an amulet to please the gods AND protect the wearer.

Ancient South Arabian incense burner, possibly 5th - 4th centuries BC. In...

In ancient Egypt, people wore scents in unguent cones, which were like...

The ancient world was scent-obsessed. Bonfires of aromatic woods and flowers lit the streets of Athens. Perfume-drenched doves were released at parties to flutter over guests. In Roman storerooms, burning incense did double duty: perfuming the goods and repelling rodents. In ancient Egypt, Hebrew wives threw mint on their hard dirt floors.

An evocative depiction of the decadence of scent in the Roman era....

The first known aromatic jewelry were the necklaces of Ancient Egypt fashioned from beads of skhab - made from an ancient recipe for a scented paste made from ambergris, rose water, saffron, cloves, musk and nutmeg. They are said to retain their scent for years. The necklace is still worn today in parts of the world, and there are strict rules surrounding their wear, since they are known to be such a powerful aphrodisiac. They are worn only by married women, and only when they are with their husband. If the husband is away, the necklace has be kept in a chest. Unmarried women are not even permitted to touch it.

Skhab necklace Ambergris mixed with spices, metal, plastic 20th century Tunisia, Africa,...

Photograph of woman wearing skhab necklace, c. 1890

Fast forward to the Middle Ages, a time that's infamous for poor personal hygiene. It's true that St. Francis of Assisi regarded dirtiness as a mark of holines, and some people took pride in their body odor. France's Louis XIII (1601 -1643) once boasted, "I take after my father, I smell of armpits." However, for most people, smelling good was as important then as it is now. And when the Crusaders returned from the East with a multitude of exotic scented items, the European populace welcomed them with open arms. Nutmeg, cinnamon, pepper, and cloves were some of the most important and valuable trade items in the world - at one point an ounce of nutmeg was worth an ounce of gold. And the richest people in Europe needed a way to conspicuously show off their new scented treasures.

German pomander, 16th century, gilt silver. In the collection of the Metropolitan...

This pomander is said to have belonged to Mary, Queen of Scots...

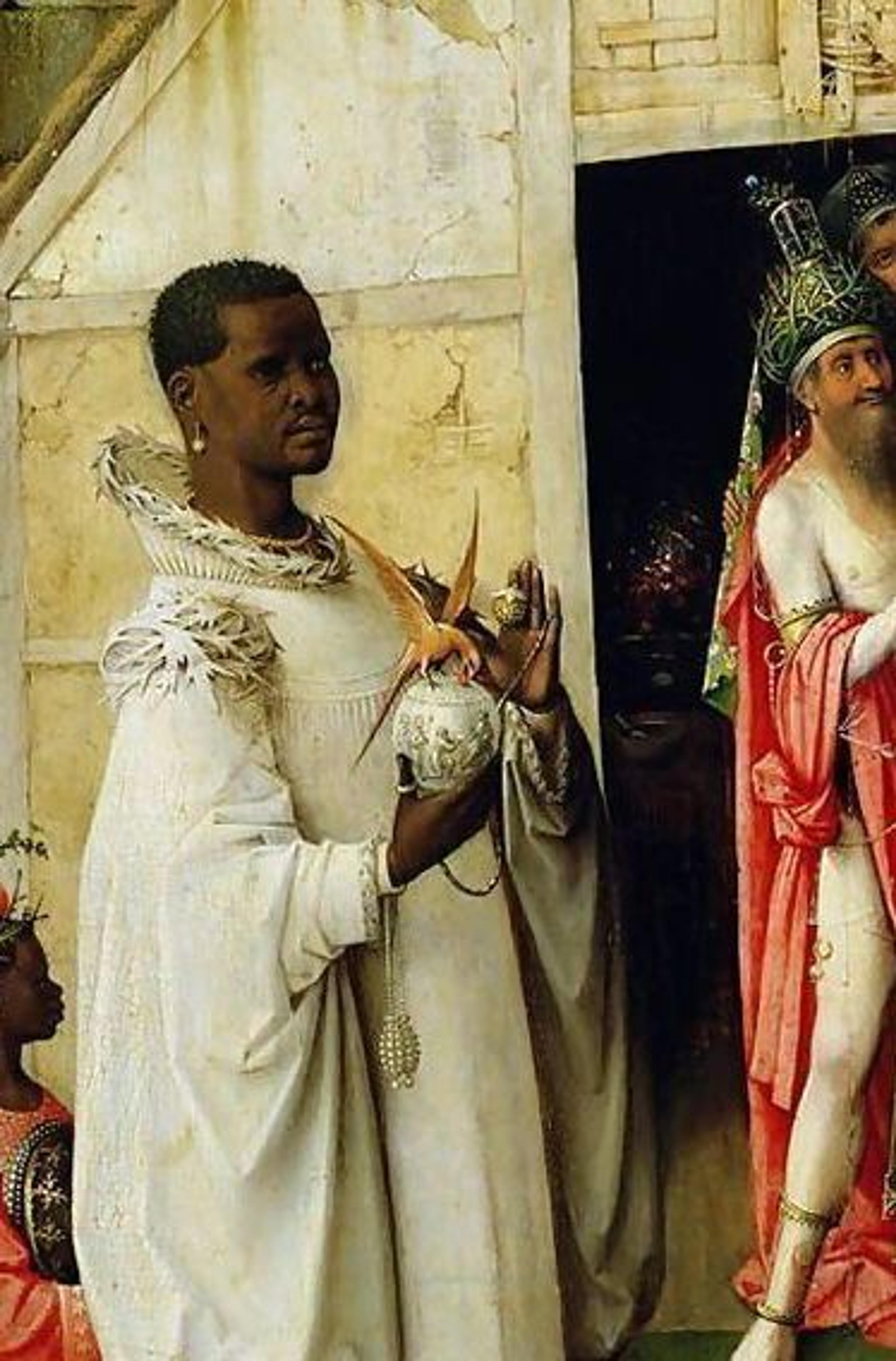

Enter the pomander. In 1174, Emperor Frederick Barbarossa received a gift of "golden apples" filled with musk from King Baldwin of Jerusalem. The word is derived from the French pomme d'ambre: apple of ambergris. Ambergris, sometimes called the treasure of the sea or floating gold, is a solid, waxy substance that originates in the intestines of sperm whales. Found off the coasts of Japan, China and Greenland, ambergris acts as a scent stabilizer and adds a musky character to perfumes. People became obsessed with it.

Fortune's Favorite by Lawrence Alma, 1895 (Showing off possibly amber or ambergris...

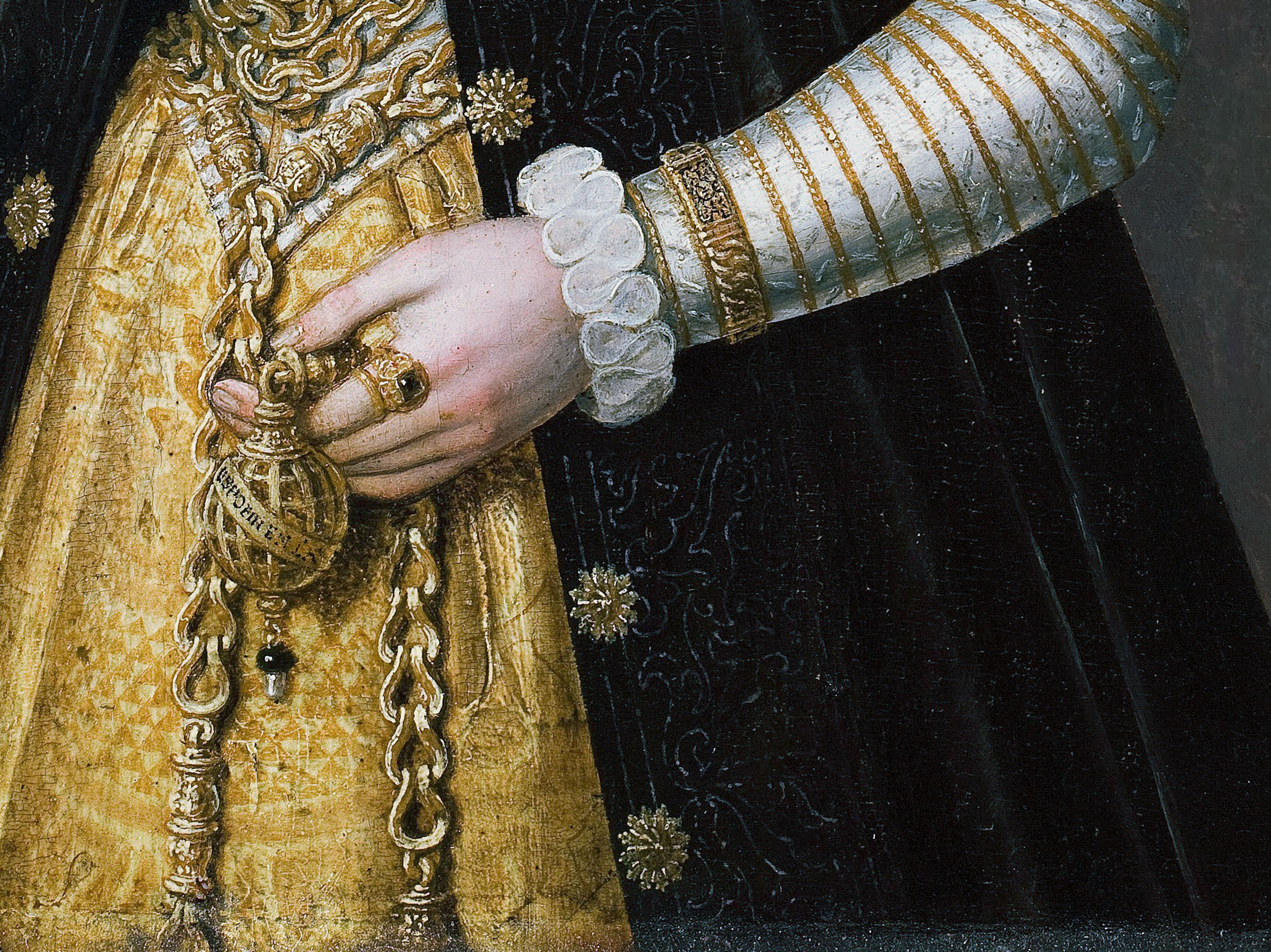

Made from silver or gold, the apple or orange-shaped pomander was conceived to protect the perfume and to distribute it. The cages opened with a hinge and perfume - sometimes multiple types - were placed inside. Large pomanders were hung from chains worn around the waist, and small ones the size of thimbles could be worn on bracelets, necklaces or less often, rings.

Pomander of partially gilded silver and niello, made in Italy, 1300-1400. From...

The pomander was seen as such a powerful amulet that even when empty, it was thought to guard both the wearer and those in close proximity from disease.

Portrait of the Infant Maria Anna, c. 1607, Juan Pantoja de la...

The Adoration of the Magi (detail of King Balthazar holding a pomander,...

Throughout the Middle Ages, the idea remained that disease spread through bad smells, stuffy air and rotting materials. The name for mosquito-born malaria actually means "bad air" in medieval Italian. Smelling good wasn't just a matter of vanity, it was a health concern. People perfumed themselves not so that they would necessarily smell pleasant to others, but so that they didn't have to smell their neighbors. Add in horse-filled streets and casual attitudes toward sewage; this meant bad smells were everywhere.

In plague-ridden Europe, it was believed that disease was transmitted through foul odors known as "miasma", a noxious form of poisoned air also known as "night air."

People figured if bad smells created illness, GOOD smells must repel it. Famously, plague doctors wore conical beak-like masks to protect themselves from contracting the disease. The beak could hold dried flowers (including roses and carnations), herbs (including lavender and peppermint), camphor, or a vinegar sponge, as well as juniper berry, ambergris, cloves, labdanum, myrrh, and storax. They believed the aromatic respirator prevented transmission of the bubonic plague, but more likely, it was their head-to-toe leather suits that created a barrier against disease-carrying fleas.

The first alcohol-based perfumes were developed in the late 14th century. This was a watershed moment for fragrance, making it easier to produce and thereby more accessible. That accessibility moved perfume out of the category of the sacred, and by the 18th century, into the realm of fashion. A tiny sponge would be drenched in an alcohol or vinegar-based fragrance and then housed in a portable smelling box known as a vinaigrette. The scents were sharp rather than sweet, and were used to stimulate and restore.

17th century scent case fitted with a squirt vinaigrette

A fainting woman is revived with smelling salts or other sharp scent....

In the late 18th century, ladies wore their vinaigrettes on their chatelaines. Think of a cross between a charm bracelet and Swiss Army knife, but worn on the belt. The concept derived from the keys that medieval castle-keepers worn on their belts. Since pockets and handbags weren't yet en vogue, this was the way to keep the essentials close at hand. In addition to the vinaigrette, a lady might wear scissors, thimbles, tape measurers and notepads on her belt. By the end of the 19th century, a lady's chatelaine frequently held a small flask of ammonia-based smelling salts (for the fainting spells brought on by all those tight corsets)

Chatelaine, 1863 – 1885, Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Downtown Abbey's Mrs. Hughes wearing a chatelaine.

In the 20th century smelling salts were out and liquid perfumes were in. But aromatic jewelry isn't going anywhere. From Cartier to Tiffany's, every major jewelry house has developed and marketed some aromatic jewelry. Vintage perfume jewelry - including Elsa Peretti's gorgeous sculptural vessels she designed for Tiffany & Co. - remains highly collectible.

Christian Dior. Poison wrist cuff flacon, 1986.

Halston (Ewan McGregor) and Elsa Peretti (Rebecca Dayan) discussing their perfume necklace...