Although we might overlook the presence of birds in our daily lives, they are much revered in the art lexicon. The earliest prehistoric paintings include birds. Ancient Egyptians believed all life emerged from an egg and that the Sun God Ra was born from the primordial egg. The Romans developed a practice called augury, a religion that interprets omens from bird behavior. The word auspice has a Latin root that means “one who looks at birds.” (See the section on Eagle below for the role the Eagle played in Ancient Rome.)

Earring with bird, Etruscan, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Earrings with pendants of birds, Greek, 4th century B.C., Metropolitan Museum of...

In a superstitious Medieval world, it was believed that birds had miraculous curative powers. For example, the plover, after breathing the breath of a sick person, was thought to carry the sickness into the heavens, and away from the individual.

Gold disc pendant with cloisonné triskele of bird heads, 7th century. The...

Silver brooch, with a gold backing and pavé-set with turquoises, in the...

In early Medieval art, an image of a small bird often depicted the mother-child relationship. In later works of art (both religious and secular), that bird is almost always a goldfinch. By the Renaissance, the goldfinch had become something of a common household pet. It would be tied to a string and given to a child.

Victorian fascination with ornithology grew throughout the 19th century as books like John James Audubon's Birds of America became best sellers and spurned hobbies like bird watching and maintaining aviaries. That there could be a sentimental meaning attached to each bird heightened the collective interest in the subject. That secret language of birds was reflected in Victorian jewelry: everything from bird brooches to bird earrings was in fashion.

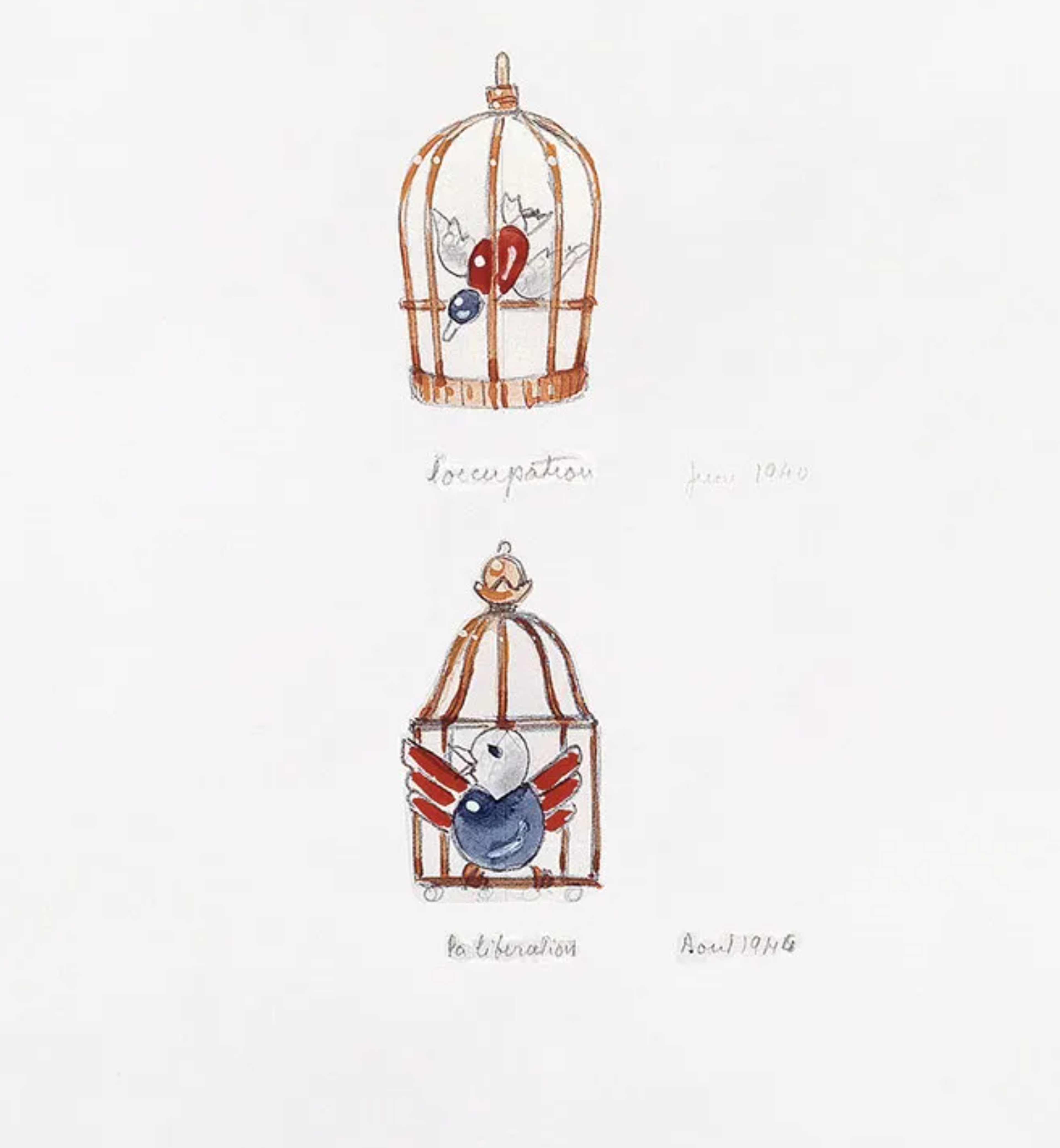

Cartier design of the caged and freed birds made during and after...

Van Cleef & Arpels bird of paradise brooch, 1942. The gems are...

During World War II, bird motifs symbolized hope in occupied France. For some jewelers, they also became signs of resistance. After Cartier made a caged bird brooch, in the colors of the French flag, designer Jeanne Toussaint was questioned by the Gestapo. They thought the brooch, displayed in the store's window, was too provocative. She convinced them that it was an old Cartier design. (It wasn't.)

After the war, Cartier produced a brooch of a bird singing in a cage with its door wide open. They named it L'Oiseau libéré. Birds continued to be a symbol of post-war freedom and jewelers crafted large elaborate pieces to emphasize a return to glamour. Let's journey into the world of birds and their symbolism. (We'll end with a jeweled ornament that incorporates a feather and has a starring role in Bridgerton.)

The 83-carat peacock brooch designed by Cartier in 1948.

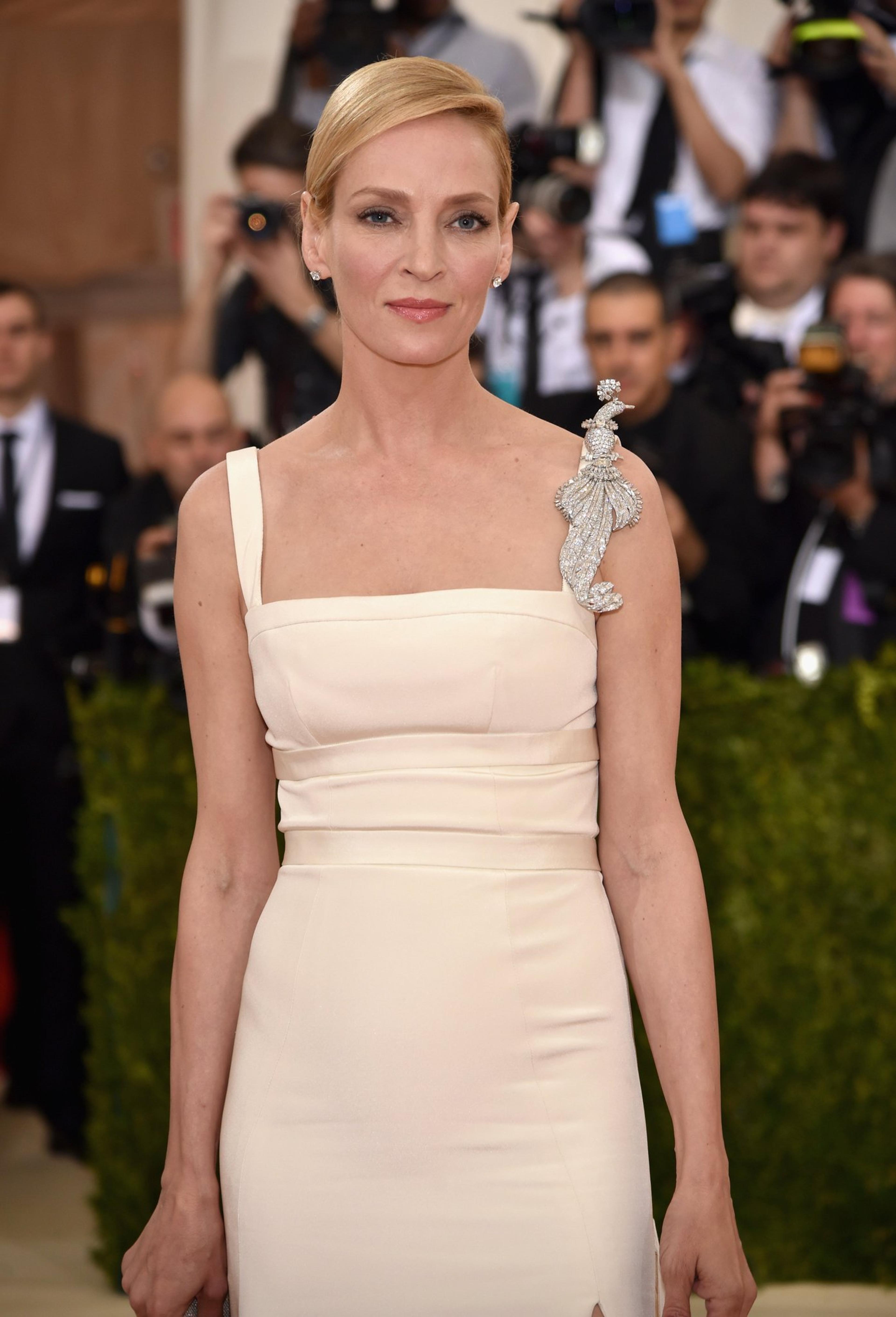

Uma Thurman wearing the Cartier bird brooch to the 2016 Met Gala....

The Owl by Valentine Cameron, 1863.

Owl head brooch, made by Castellani, 1860. Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The owl has been associated with wisdom since ancient Greece. It was the emblem for Athena, the goddess of foresight and knowledge. It was also considered a symbol of wealth and was used as a motif on coins. The Plains Indians wore owl feathers to ward off evil spirits.

Not everyone embraced this admittedly strange looking bird. In many cultures, the hooting of an owl was considered an ill omen. In ancient Egypt, it was used as a symbol of death: It was believed that the bird would protect the spirits as they passed from one world to another. In superstitious medieval Europe, the nocturnal habits of an owl were enough to have it branded as a witch.

Owl brooch, 1965. The Victoria and Albert Museum.

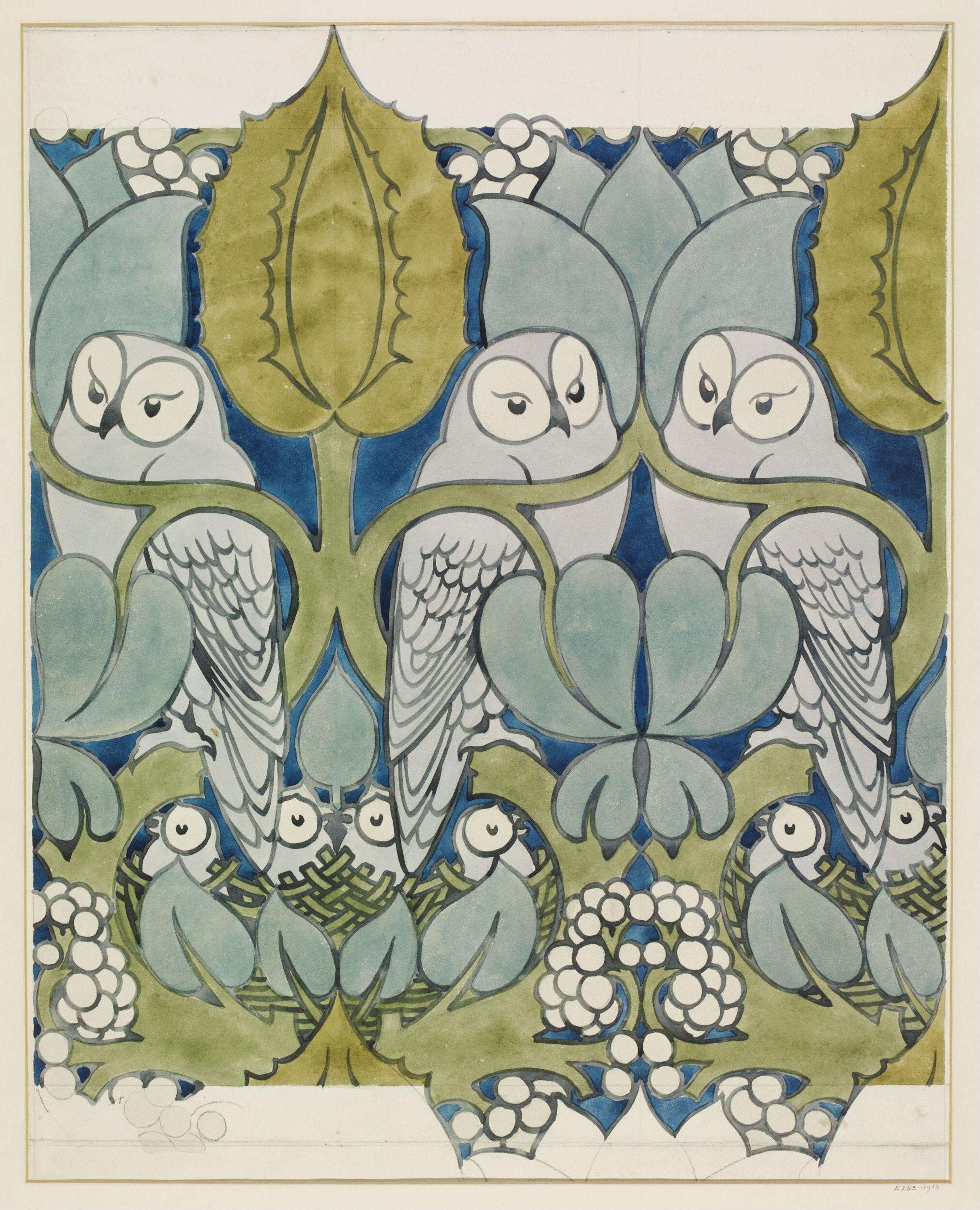

Design for 'The Owl' wallpaper and textile pattern by C.F.A. Voysey, 1897....

Thankfully, the Victorian obsession with ornithology rescued the owl from the satanic associations of the medieval mindset. British poet Edward Lear helped the owl's image when he awarded the bird a title role in his popular children's poem, The Owl and Pussy-Cat (1867), and Arts & Crafts designer seized the bird as the perfect design motif.

Rafaela Flores Calderón with gray parrot, Antonio Maria Esquivel, 1842. Museo...

Enameled gold parrot pendant, 1600-1650. The Victoria and Albert Museum.

Well known for its ability to imitate the human voice, parrots have historically symbolized eloquence. During the Medieval period, the bird was considered to be a symbol of purity. It was thought that the female parrot made her nest in the orient where it didn't rain so therefore it wasn't stained by mud. (Try to put aside the illogical reasoning).

The purity metaphor continued through the Renaissance, where the parrot was considered a herald of the Immaculate Conception (since the Virgin conceived by the Word).

Parrot in Françoise-Renée de Carbonnel de Canisy, Marquise d’Antin by Jean-Marc Nattier,...

The Countess of Kellie (Scotland) insisted on being painted with the parrot...

Their rarity and difficulty to obtain also made them a symbol of wealth. (There's an entire Wikipedia page devoted to 17th century portraits with parrots) The influx of parrots into 18th century Europe arrived on ships returning from Africa, the Americas and the East Indies. Caged birds were a common feature of the Victorian parlor and provided imaginative fodder for the poetry and novels of the period.

“A sort of cage-bird life, born in a cage, Accounting that to leap from perch to perch. Was act and joy enough for any bird.” — Elizabeth Barrett Browning, Aurora Leigh, (1865)

Three-year-old Archduchess María Teresa of Austria (niece of Marie Antoinette) with her...

Parrot pendant, Spanish, late 16th-early 17th century, Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Swallow amulet, 664-380 B.C. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Two photographs of Albert Edward, Prince of Wales in a silver swallow...

The swallow has long been associated with the return of spring. As such, they are birds of good luck, happiness and hope. They are the embodiment of a sailor's hope of seeing land again. (There is a rich history of sailors' swallow tattoos.)

In San Juan Capistrano, there is an annual Swallows Day parade every March to celebrate the bird's return to the Southern California town after their long-haul commute from Goya, Argentina (a 6,000 mile journey). In jewelry, a swallow often represents faithfulness and a wish for a loved one's return.

The Sovereign's Sceptre with dove. Made for the coronation of Charles, II...

A Saint-Esprit pendant. The dove, symbol of the Holy Spirit (Saint Esprit),...

In ancient Mesopotamia, doves were the symbols of Inanna-Ishtar, goddess of love, sexuality and war. The bird was associated with her Greek equivalent: Aphrodite and Roman: Venus. From there, the dove became a symbol of peace and love in Christianity, Judaism and Islam. In the sentimental Victorian age, doves were a particularly favorite motif. A dove holding an olive branch symbolized hope, friendship and peace.

Roman mosaic depicting doves drinking from a bowl 2nd century AD. Capitoline...

Micromosaic brooch of two flying doves, 1860. The Victoria & Albert Museum.

In 1737, a Roman mosaic depicting doves drinking water was uncovered at Emperor Hadrian's Villa. The subject and the mosaic technique served as great inspiration to artists and designers. The dove was a particularly popular subject for micromosaics, a type of mosaic technique that uses tiny glass pieces, or tesserae, to create a design.

Dove on an olive branch by Sir Edward Burne-Jones, 1895. Metropolitan Museum...

Gold dove holding a white enameled envelope, 1850. The British Museum.

A Roman aquila, latin for eagle, was an ubiquitous symbol in ancient...

A French Imperial Eagle, carried by Napoleon's regiments. This one was damaged...

The eagle was the symbol of Zeus (or Jupiter, for the Romans). It still represents power and majesty. Its massive wing span commands attention. Some have said that eagles were the world's first logo: the Roman Empire was quite good at branding and they adopted the Eagle as a symbol of their military might. An image of the eagle appeared above the letters SPQR: Senatus Populusque Romanus (the senate and people of Rome).

In the chivalric Medieval period, the eagle became a recognizable symbol of power and pedigree. The first Holy Roman Emperor, Charlemagne incorporated the eagle into his coat of arms in 800.

The Crown of Empress Eugénie with eagle motifs, 1855. The Louvre.

Known as an "Eagle pendant," Chiriquí, 800-1519 A.D. Bird pendants like this...

The eagle was the personal symbol for Roman-obsessed Napoleon. And the United States took the eagle as its national symbol in 1782. It wasn't a generic eagle -- this was the North American bald eagle. The bird was sacred in some Native American culture, like the Lakota (who give an eagle feather as a symbol of honor) and the Choctaw (who consider the eagle to be a symbol of peace).

One of Queen Victoria's twelve wedding train-bearers wearing her turquoise eagle brooch...

Prince Albert designed this eagle brooch that was given to each of...

Prince Albert, who was always eager to bring a Germanic influence (like Christmas trees) to Britain, used the image of the German eagle as inspiration for the brooch designs that were made and gifted to Queen Victoria's train-bearers. When (at age 17) the couple's eldest daughter wed Prince Frederick of Prussia, Albert designed six golden bracelets, each with the image of the Prussian eagle with diamond encrusted wings. Prussia adopted the eagle as its symbol in 1871, and, later Adolf Hitler would co-opt the ferocious image of the eagle as a secondary symbol of the Nazis.

Brooch in the form of an eagle fighting a snake, 1860. The...

A brooch by Castellani of Rome, the leading firm making jewelry inspired...

If any bird can transcend pigeonholing as emblem of a megalomaniac, it must be the eagle. After all, it is a Biblical bird. In Exodus God says to Moses: ‘You yourselves have seen what I did to the Egyptians, and how I bore you on eagles’ wings and brought you to myself.' And in Isaiah: 'But they who wait for the LORD shall renew their strength; they shall mount up with wings like eagles; they shall run and not be weary; they shall walk and not faint.'

Grand Duchess Maria Feodorovna, Alexander Roslin, 1777. Hermitage Museum.

Socialite Evalyn Walsh McLean (her father discovered a gold mine) wearing an...

We end our look at the symbolism of birds with jewelry that incorporated actual bird feathers. The first aigrettes were worn in (modern-day) Turkey as turban embellishments during the Ottoman Empire (1281-1924). At the end of the 16th century, they were adapted as women's hair adornments. They cycled in and out of fashion from the 17th through to the 20th century.

Daughter-in-law of President Martin van Buren wearing ostrich feathers. The popularity of...

Depicting London society in 1813, Daphne Bridgerton wears an aigrette as she...

The word is French for egret, a large Egyptian white heron, the source of the majority of the feathers. Society ladies and their couturiers (like the great Worth) considered them essential to a complete evening look. Jewelers designed elaborate headdresses to accentuate the feathers. And when giant feathers fell out of fashion, they updated the look by crafted feathers from gemstones. It was the perfect look for the fashionable bobbed hair of the 1920s. But after World War II, all hair jewels seemed frivolous and (sadly for us!) the aigrette became a thing of the past.

Aigrette with diamonds, turquoise, an emerald and other colored stones, 1810. The...

Boucheron diamond and pearl aigrette tiara sold at auction by Maison Boule...