A cameo is a stone (or other hard material like a shell or even glass), which has been carved away to produce an image in relief.

Sardonyx (a type of agate) cameo portrait of the Emperor Augustus, ca...

Three-layered sardonyx cameo engraved with a portrait of Augustus wearing the aegis...

The upper layer is cut away in raised relief while the lower one is revealed as a blank ground. Ancient cameos were often made from semi-precious gemstones. Any stone with a flat plane where two contrasting colors meet could be used for cameo work. These are called “hard stone” cameos.

Less expensive versions of the hard stone cameo are made of shells or glass. (The opposite of a cameo is an intaglio, where the design is carved below the surface. These were often used as wax seals.)

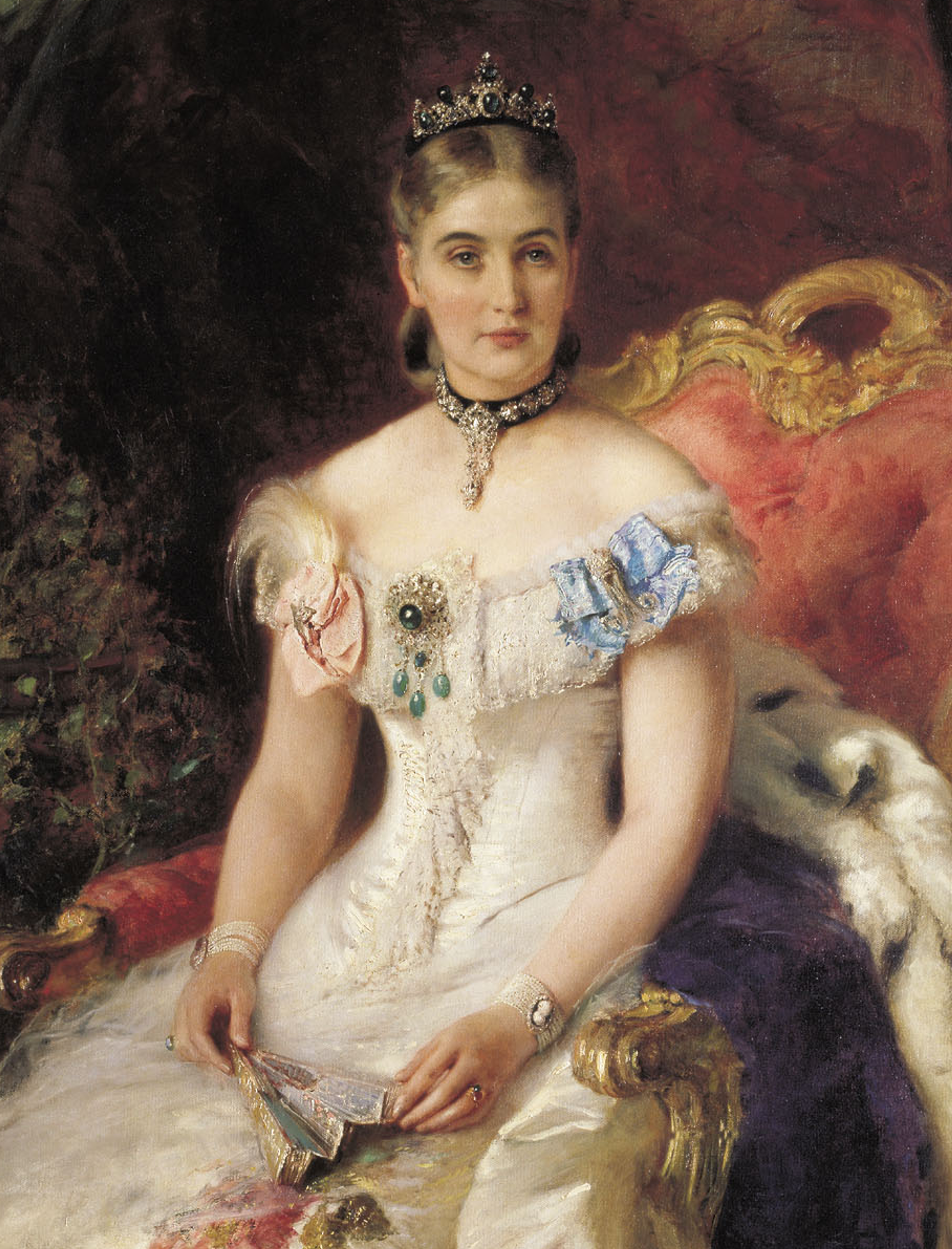

Portrait of Countess V. A. Volkonskaya by Konstantin Makovsky, 1884. Art Museum...

Fanny Holman Hunt by William Holman Hunt, 1866.

Cameo carving became hugely popular in Ancient Greece, following the late 4th century B.C. reign of Alexander the Great. The sardonyx, a favorite stone for carvers, came from India. Alexander’s conquests opened up trade with India, which made it easier for carvers to get the stone, and made cameos more proliferate.

In Ancient Rome, cameos were worn as a sign of wealth and taste, but also to profess a devotion to a god or political entity.

Wearing a cameo pendant. Portrait of a Young Woman, 1540-1545. Hans Holbein...

During the uber religious medieval era, cameos were used to express spiritual devotion. Many were used to adorned venerated devotional objects in monasteries and churches. Although cameos were much-appreciated, the craft of carving was hardly practiced.

The pendant on her necklace is a cameo copy of the ancient...

The Suicide of Lucretius by Paolo Veronese, c. 1583. Kunsthistorisches Museum.

Renaissance fascination with all things from ancient Greece and Rome turned many into passionate collectors. Lorenzo de’ Medici was one of many ancient cameo collectors. The art of carving was revived. Both new and old cameos were placed in spectacular gold settings.

As with other collectibles, rarity, not age, often determines value. So Renaissance cameos are actually more valuable than Roman ones, because so many cameos were produced in ancient Rome.

Detail of Princess Borghese by Robert Lefebvre, 1806. Versailles.

Detail from Caroline Murat, later Queen of Naples, and Her Daughter by...

In the 1750s, excavations of the ancient Italian cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii captivated the world. The sites became must-sees stops on the “Grand Tour.” Travelers could purchase ancient cameos or newer creations from the cameo carving shops.

When purchasing new cameos, many tourists gravitated toward “lava cameos.” These were cameos carved from volcanic breccia. A volcanic cameo pinned on one’s blouse was proof of a person’s well-traveled status.

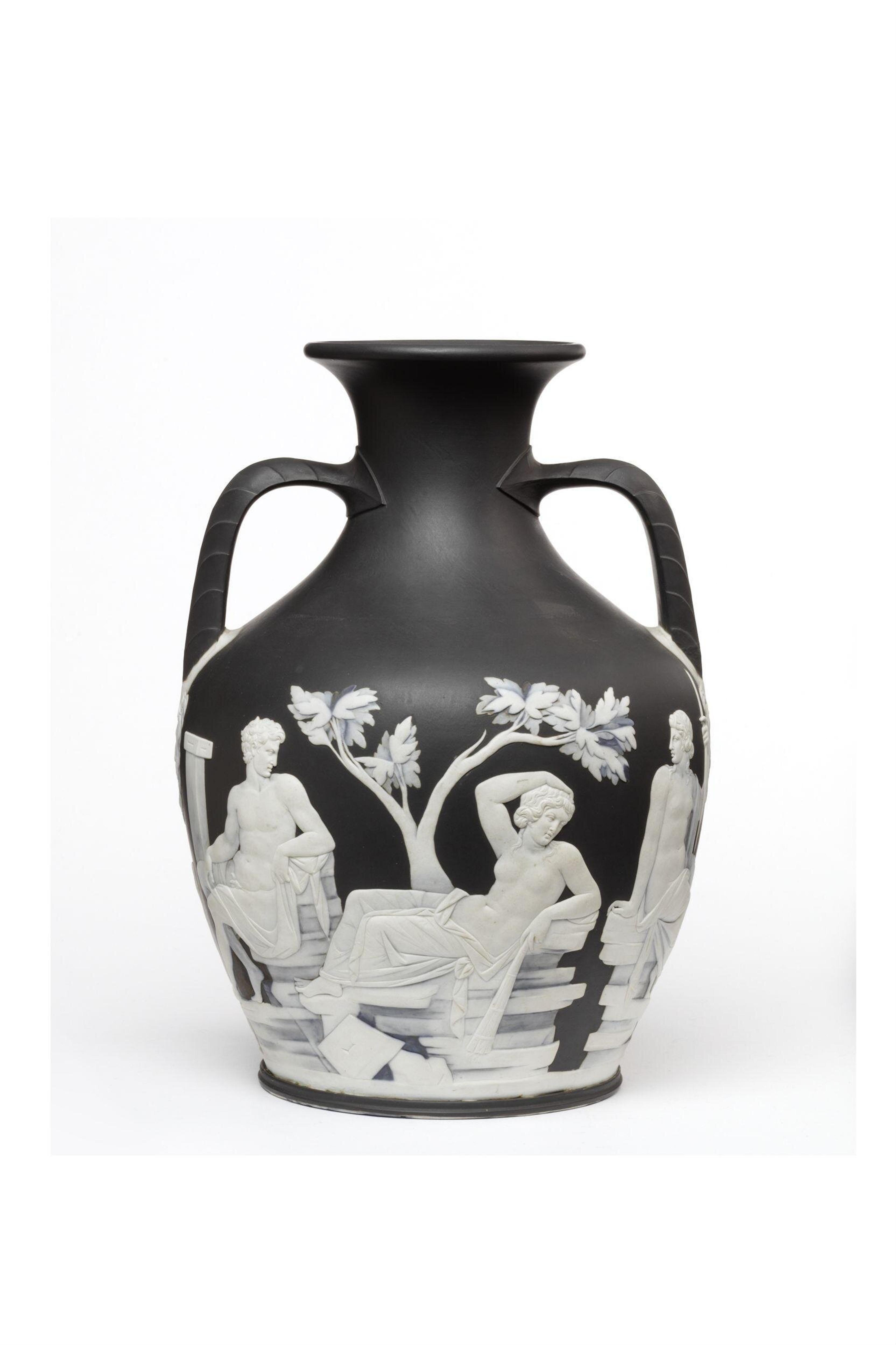

In 1845, the vase was (purposefully) shattered by drunk man. It was...

Josiah Wedgwood’s Portland Vase, c. 1840-60. He made many editions of the...

However, if you had money and connections, you wanted the real (Roman) thing. The best known antiquities collector was Sir William Hamilton (1730-1803), who used his position as British diplomat in Naples to acquire antiques and sell them in Britain. He brought (literally) boatloads of ancient relics back. Many of them ended up with his biggest customer: The British Museum. (And yes, the whole business seems more than a little shady. The British Museum has been widely criticized for failing to repatriate artifacts).

In the middle of her belt, the Duchess wears a Wedgwood ceramic...

Wearing the same cameo. Madame d'Aguesseau de Fresnes, Élisabeth Louise Vigée Le...

Amongst those relics brought to Britain was a glass cameo vase, later known as the Portland Vase (named for one of its owners: The Duchess of Portland). The vase was produced in Alexandria in A.D. 40. It had been uncovered in Rome during Renaissance era archeological excavations. There have been only fifteen complete objects made from Roman cameo glass that have survived. So the vase was a big deal.

When it arrived in Britain, Potter Josiah Wedgwood became completely captivated. He even managed to borrow it, in hopes he might be able to create a reproduction. And after four years and thousands of trials, in 1790, he succeeded in creating an exact replica of the Portland Vase. The Wedgwood version was crafted in, what would be his signature stone wear, Jasperware. Wedgwood put his replica on display in London and he sold viewing tickets. He created such frenzy for the Vase that people had to be turned away. It was the beginning of the Wedgwood cameos.

Official mistress of King Louis XV in 1745, Marquise de Pompadour wears...

Joséphine de Beauharnais, 1808 by Andrea Appiani/Wikimedia Commons.

In France, even the French Revolution couldn’t squelch passion for the cameo. Napoleon and Josephine seized on the cameo’s Roman past as a way to align themselves with the ancient world. Josephine eschewed the frills of the Rococo era in favor of an antique style of dressing. Even Napoleon’s coronation crown was decorated with cameos.

Created for the coronation of Napoleon I, 1804. Louvre Museum.

Portrait de l'Impératrice Joséphine (1763-1814) by François Gérard, 1807. Château de Malmaison.

“A lady of fashion wears cameos on her belt, cameos in her necklace, a cameo on each of her bracelets, a cameo in her diadem.” —Journal des Dames, 1806

The jugate heads in this cameo are of Prince Albert and Queen...

Queen Victoria wearing the “Royal Order of Victoria and Albert” on her...

In Britain, the cameo revival first occurred during King George III’s reign in the mid 18th century. His granddaughter’s (Queen Victoria!) enthusiasm for cameos created such a demand that they would become mass produced by the second half of the 19th century. Those mass-produced cameos were made of shell and could be made in a matter of days (versus the months it might take to carve a hard stone cameo). While earlier cameos usually depicted allegorical, mythological or historical images, cameos during the Victorian era usually depicted a female profile. (Most cameos depicted right-facing profiles, so today, left-facing are more valuable.)

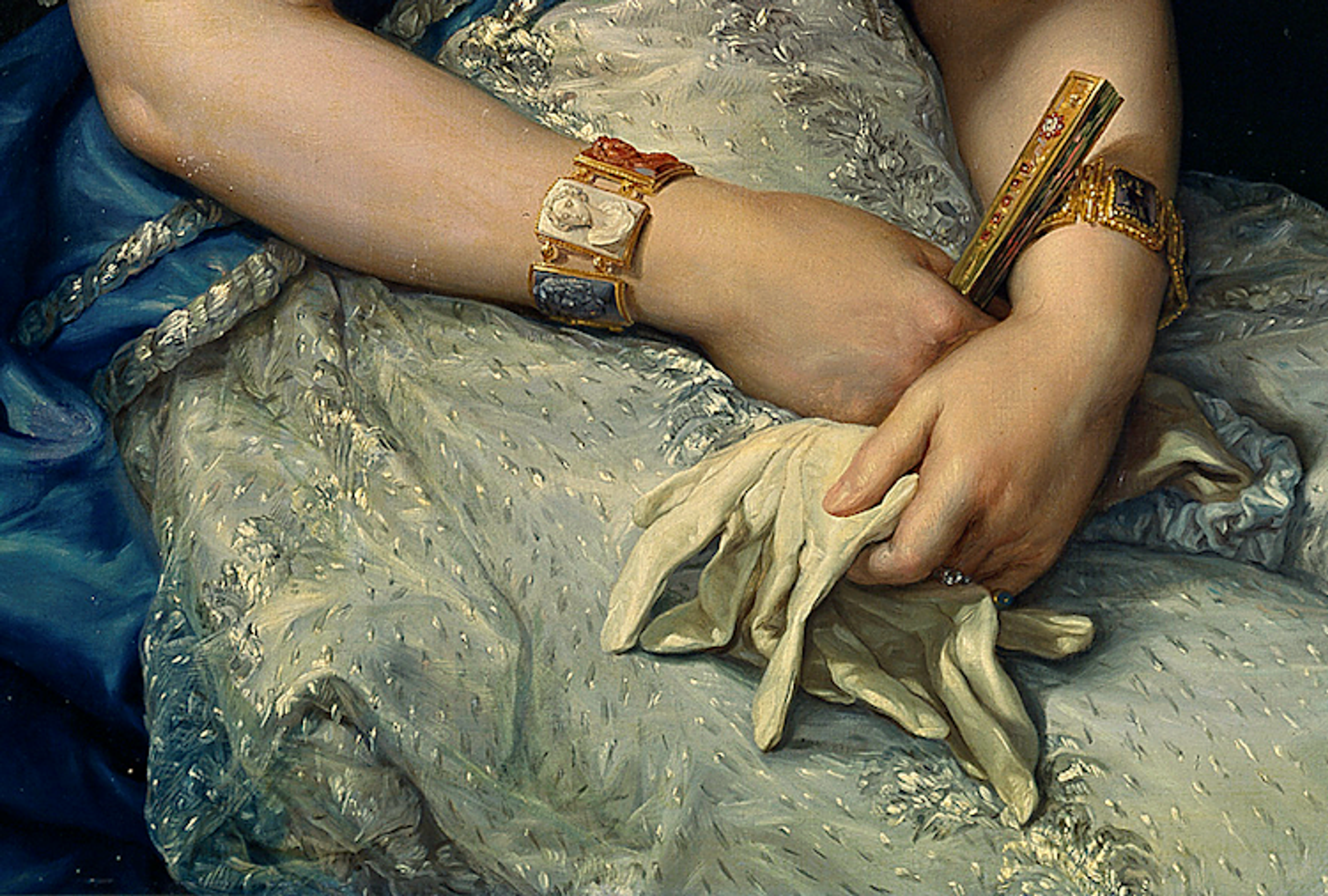

Mrs. Stuart is wearing a bracelet of six cameo links, each surrounded...

Cameo bracelets on wrists of Maria Antonia who was the youngest daughter...

After World War II, inexpensive cameo jewelry made out of synthetic materials such as celluloid and bakelite became popular. Cameos were also made out of natural materials like jet and amber. By the late 20th century, plastic and glass were used.

You can still pick up cameo souvenirs on your own Grand Tour from shell cameo carvers working in Torre del Greco, Italy. Located at the foot of Mt. Vesuvius, the area has an abundance of lava, coral and shell, making it the perfect spot for cameo design.

Cameo parure in a style known as “archaeological jewelry:” tiara, necklace and...

Necklace with cameo of Veronica’s Vail, c. 1870 by Castellani in the...