Jewelry crafted from human hair has existed at least since the Middle Ages, when English knights and other men might receive lockets containing wreaths or hearts woven from their lover’s — ummm — pubic hair. (What can we say? History is weird.)

Band of lace made from human (head) hair, made as a love...

However, most of the hair jewelry that exists today comes from the Victorian era, and the Victorians were a little more modest about where the hair came from. In addition to their well-known modesty, they were a sentimental bunch, and they were obsessed with hair (on the head).

The Seven Sutherland Sisters were a sister act singing group. They performed...

Victorian women traditionally grew out their hair for their entire lives. Young girls wore it loose, and a mark of womanhood was pinning it up. Friends might exchange locks before embarking on long trips, and schoolgirls collected snips of hair for scrapbooks.

“Diana, wilt thou give me a lock of thy jet-black tresses in parting to treasure forevermore?” —Anne Shirley, in Anne of Green Gables, 1908

Queen Victoria's bracelet with lockets for each child: pink for Princess Victoria,...

Interior of one of the lockets on Queen Victoria's bracelet.

Hair jewelry was perfect for commemorating special moments like the birth of a baby or an engagement. Three days after the birth of their first child, Victoria, Prince Albert presented Queen Victoria with a bracelet adorned with a single pink enamel locket. A locket was added for each subsequent birth, each one containing a lock of the baby's hair and inscribed with the name and date of birth.

Bracelet of flat plaited hair with serpent clasp, amethyst drop and gold...

"Portrait of Three Girls" (1839) by Johann Nejebse, National Museum in Warsaw....

Life in the 19th century wasn’t all Grand Tour jaunts around Europe, scrapbooking parties and celebrations. Thanks to war, epidemics (diphtheria, typhus and cholera), poor sanitary conditions, inadequate nutrition, and lack of medical care, death was a constant companion for Victorians. The average lifespan was only 50 years old, and that was if you made it to adulthood. Infant and childhood mortality was extremely high. All those factors were compounded in the United States, where casualties from the Civil War (about 750,000 men) add to the death toll. This created an atmosphere where nearly every person had a personal experience with loss.

A locket belonging to Queen Victoria, set with central oval onyx, black...

The locket opens to reveal hair on one side and photograph of...

One of the cornerstones of the social framework to deal with all that death was a prescribed mourning attire. When Queen Victoria’s beloved husband Albert died in 1861, she wore jewels with his hair, but also only black clothes for the remaining 40 years of her life. England followed her lead and people telegraphed their own grief by wearing dark clothes and subdued jewelry, but usually not for four decades. If a close family member died, you’d go into “deep mourning” for a year and a half, where you'd wear only black clothing (symbolizing spiritual darkness) with no decoration, lace, velvet, or shiny materials. Eventually you’d move onto “half-mourning,” where you could wear grey, mauve, or white. You’d be able to sneak some jewelry back into rotation, but only black-colored pieces made of jet, gutta percha, Vulcanite, and a few other exceptions.

“Hair is at once the most delicate and lasting of our materials and survives us, like love. It is so light, so gentle, so escaping from the idea of death, that, with a lock of hair belonging to a child or friend, we may almost look up to heaven... I have a piece of thee here.” — Godey's Lady Book magazine, 1860

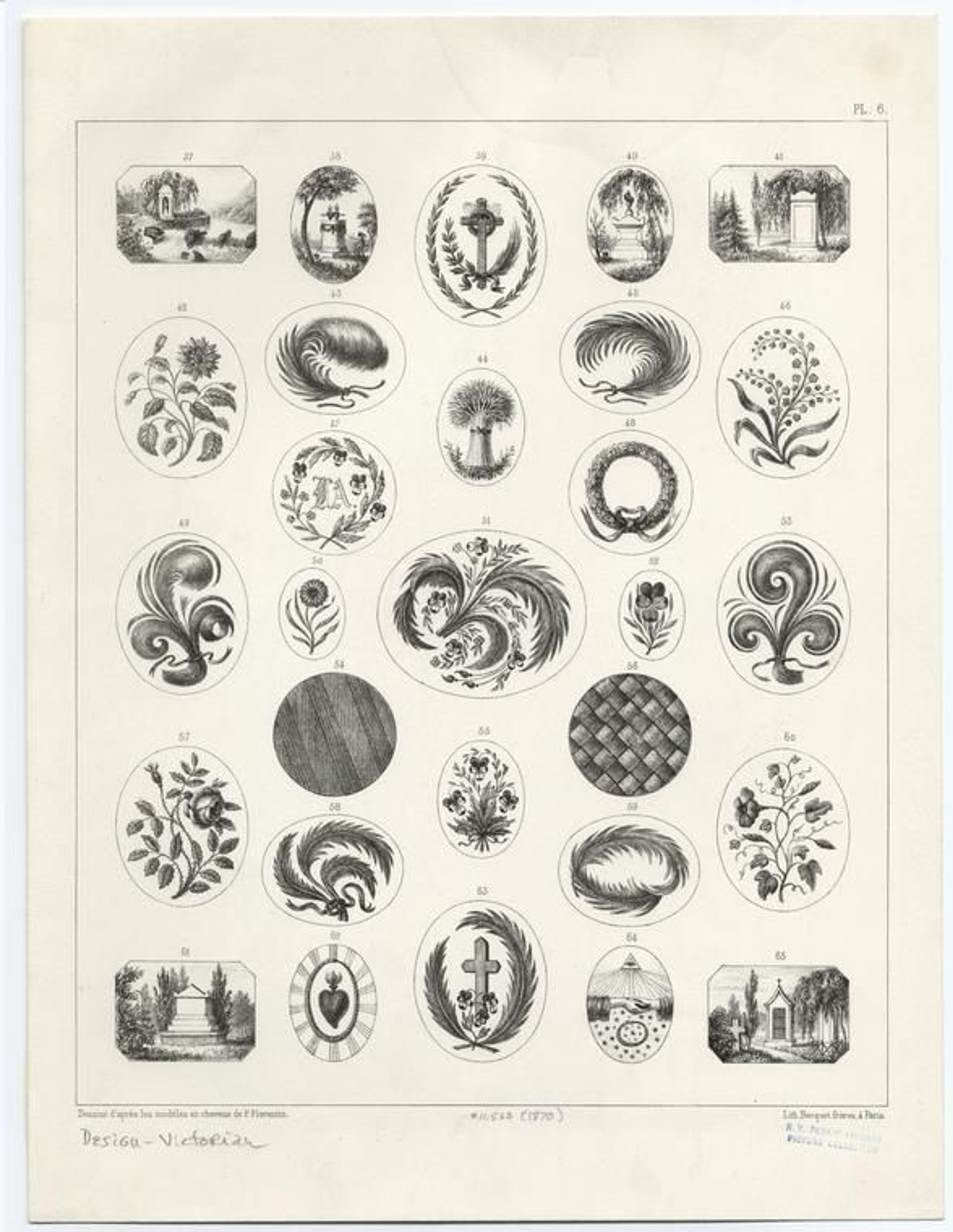

Victorian design ideas for hairwork, some to be painted onto ivory and...

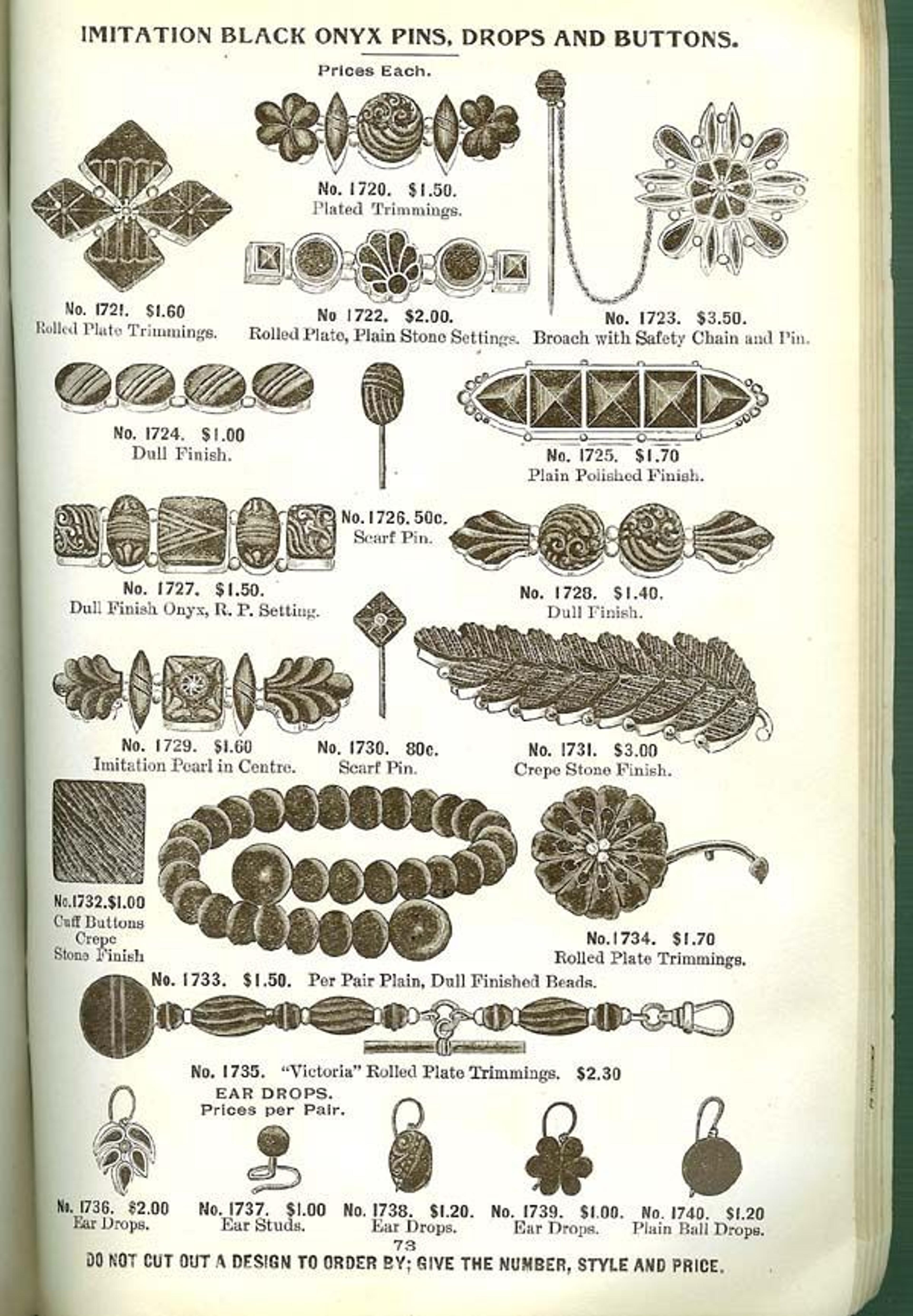

Mail-order catalog page with a selection of black mourning jewelry and their...

Mourning became big business for those supplying the bereaved. Not everyone could afford to commission a beautiful, one-of-a-kind hair jewel from scratch, so jewelers created lines of less expensive, customizable pieces with one-size-fits-all grieving slogans like Not Lost but Gone Before, Prepare to Follow and In Memory Of. You could choose an in-stock blank mourning piece with an empty locket to stash your loved one's hair, and then have the jeweler engrave the sad death details within a designated blank space. You could even purchase mourning jewelry via mail-order-catalog, a new invention in the late 19th century. The demand for intricately woven hair jewelry was so intense that in the U.K., entire towns worked to fulfill the need. In New York City, many hair jewelry workshops and retailers set up shop on Broadway. While commissioning hair jewelry was certainly easier than making it, many bereaved customers wanted absolute proof that the jewelry was definitely made with their loved one's hair.

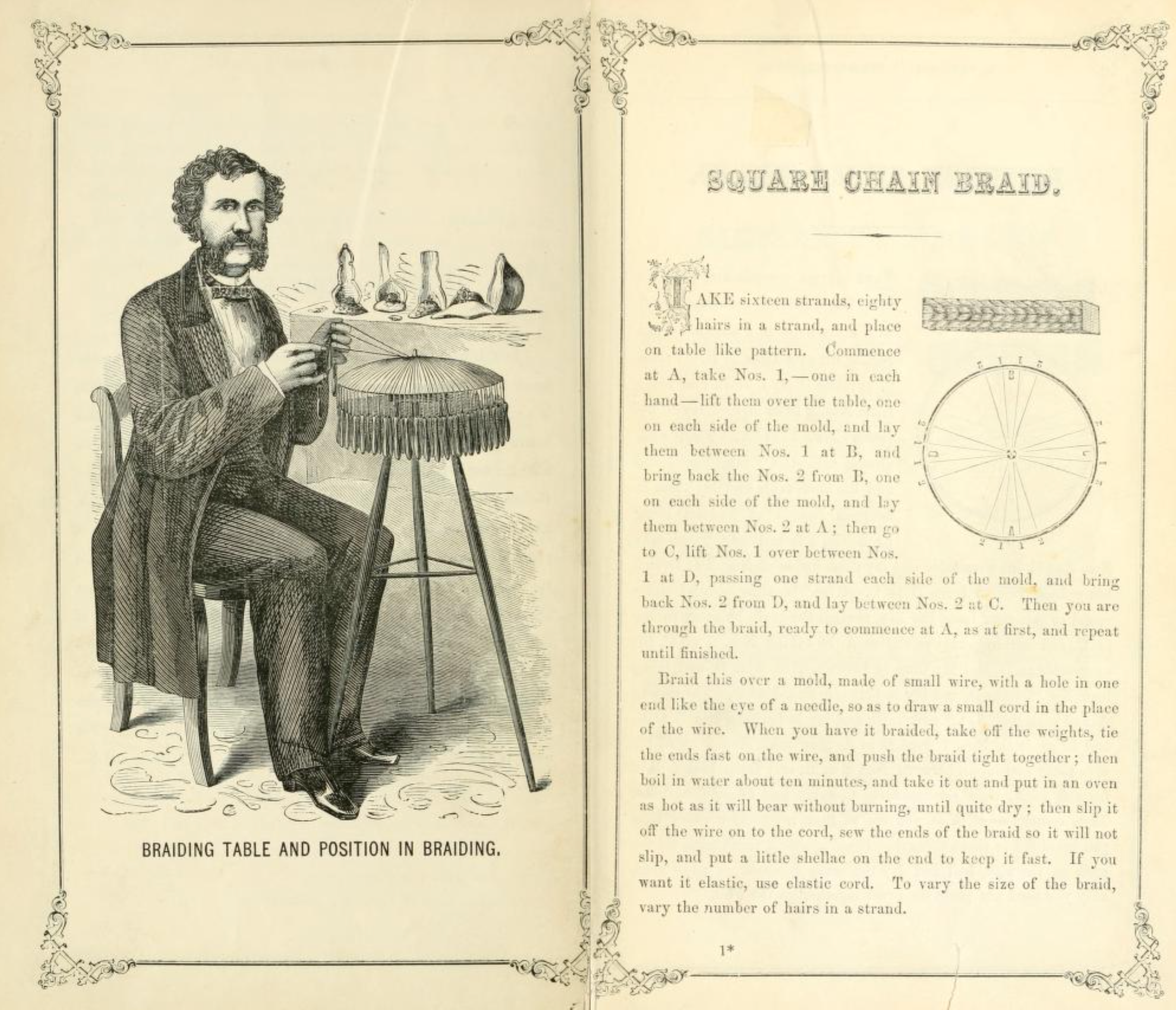

Self-instruction in the art of hair work by Mark Campbell, 1867.

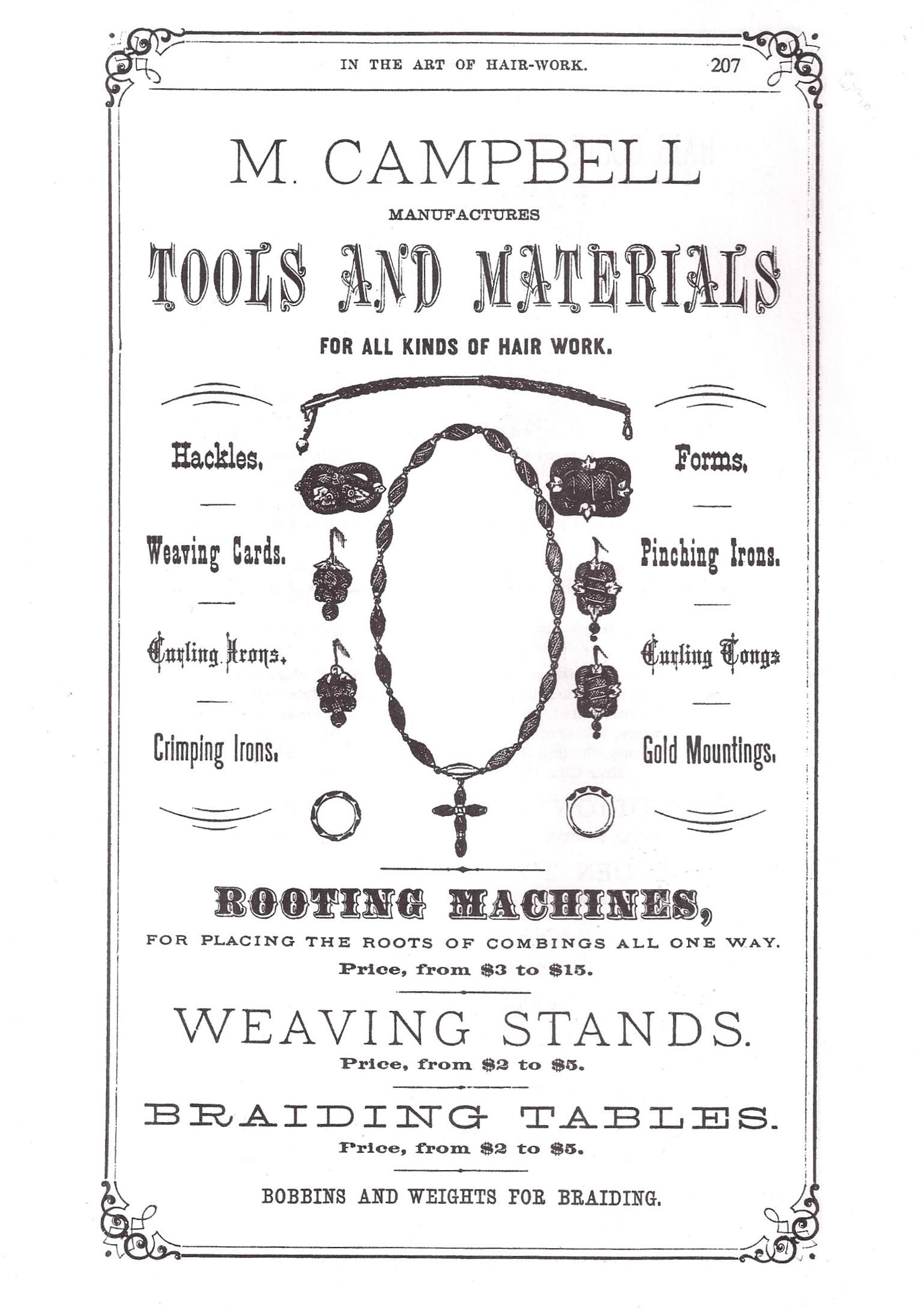

Accessories to help make your own hairwork at home.

This wasn't an idle concern; hair taken from a living person is more pliable than hair from a dead one. Some of the biggest scandals of the 19th century involved workshops swapping out hair, for either a stranger's or horsehair, which was easier to work with. One way around this worry was to DIY your own hair jewelry. Manuals like Mark Campbell's Self-Instructor in the Art of Hair Work gave precise tips on how to craft jewelry from hair and many industrious Victorians did just that in their own homes.

Queen Victoria's mourning locket for Alice, the first of her nine children...

Queen V and her family in mourning in 1879, two months after...

It’s important to remember that mourning/hair jewelry, like almost all jewelry, was a way to show off your wealth. Before Queen V made hair jewelry a hot trend for the masses, rich and important individuals set aside money in their wills so that memorial jewels could be distributed to family members and friends at the funeral. The more wealthy the deceased, the more opulent the jewels. These pieces denoted status as well as how well you were loved and remembered. Then, as today, famous people's hair (in or out of jewelry!) has been prized and rabidly collected — it feels very intimate to LITERALLY be able to hold a piece of someone. A scraggly few hairs belonging to George Washington, stored inside a brass and glass locket, recently sold at auction for about $40,000. In early September 1838, Grace Darling, the 23-year-old daughter of a lighthouse keeper, spotted a ship wreck from an upstairs window and was instrumental in rescuing nine people. She became an instant heroine, and was almost shorn bald for cutting off locks of her hair to send to admirers wanting a piece of her hair.

Mourning ring containing lock of Alexander Hamilton’s hair presented to Nathaniel Pendleton...

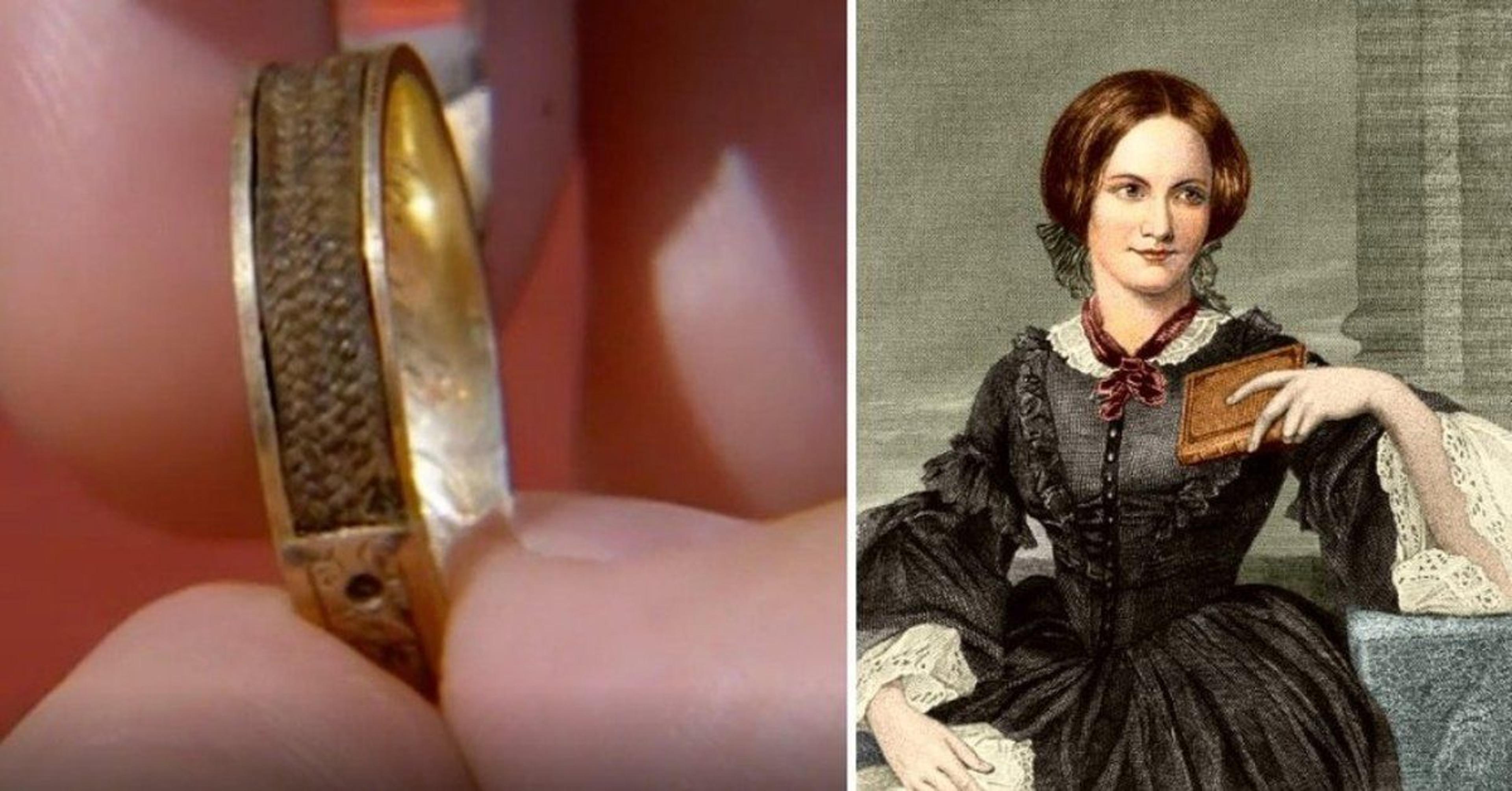

A ring set with Charlotte Bronte's hair was recently identified on Antiques...

Not all hair jewelry from the 19th century was made to be mourning jewelry. Friendship jewelry incorporating hair was still a thing, and it was often exchanged between lovers or pals who were about to be separated for a period of time, like when a sailor went off on a long sea voyage. Memory was still the main theme. When we are trying to identify whether a piece of Victorian hair jewelry is a mourning piece or a friendship/love token, we look for clues. Is black enamel involved? (Or white, indicating the deceased was unmarried.) Classic giveaway that we're seeing a memorial piece. Any classic symbols of grieving like an urn, weeping willow, woman crying at a grave, lily of the valley? Or best tell of all: are there engraved details of the memorialized person's death? A birth/death date? Age?

In contrast, friendship pieces with hair often have a more upbeat feel and incorporate symbols of affection: turquoise, hearts, clasped hands. The forget-me-not flower can go both ways. These aren't surefire ways to tell the intent of hair jewelry, but they help us make an educated guess.

With the death of Britain’s most famous mourner, Queen Victoria, in 1901, hair jewelry gradually began to fall out of fashion. It was a little fussy for the Edwardian age, but the real death knell came during the first World War. Not only were individuals were encouraged to give their money and time to the war effort rather than crafting memorial jewelry, but photography became widely available. For those who wanted a tangible reminder of a loved one, a photo locket was the gift of choice. When the United States entered World War I, in 1917, the demand for photo locket necklaces shot up. They were even available at post offices where they could be shipped to a number of war fronts.