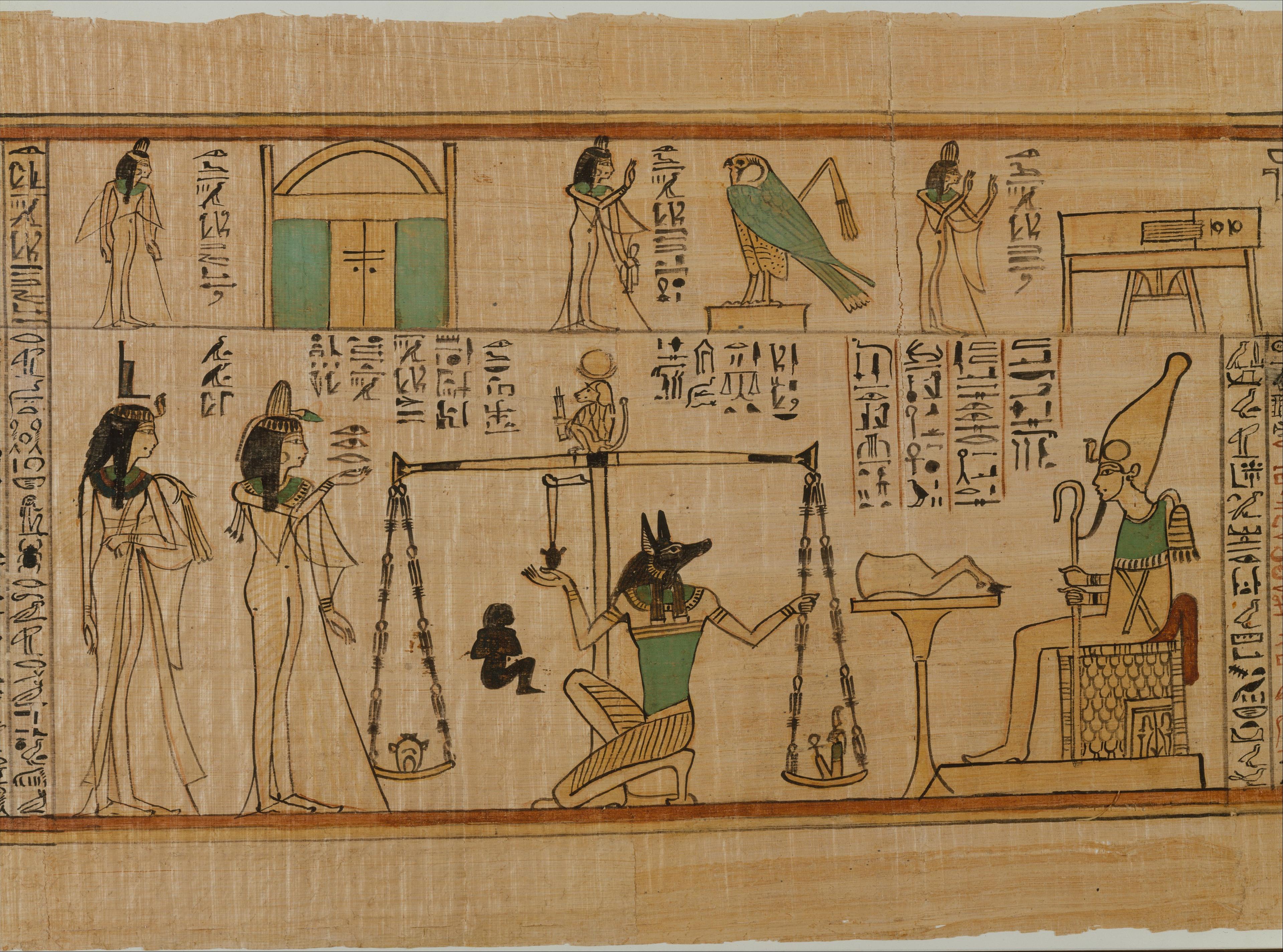

Since ancient egypt the heart has been tied to love. Ancient Egyptians believed that the heart was the center of all amorous feelings. They also believed it was the seat of the soul, and that it would be weighed at the time of one’s death. (It needed to be light as a feather to enter the afterlife.)

Nauny, a Chantress of the god Amun-Re (a woman who chanted the...

For Ancient Romans, the association between the heart and love was a given. (We also have them to thank for the placement of wedding rings, as Romans believed a vein in one's fourth finger was connected to the heart.)

However love-centric the heart might have been for the Ancients, our story of the double-clefted icon doesn't pick up until the Middle Ages.

An early depiction of the heart = love. Here the heart is...

Thought to be the earliest image of the heart icon. From the...

The heart symbol was born in the 14th century.

those first hearts were little more than decorative doodles — likely cribbed from nature — on the edges of Medieval manuscripts. Medieval Europe, with a mostly illiterate population, was all about symbols, and during the 13th and 14th centuries, this random shape began to signify love. That Medieval association of the heart shape = love has remained connected ever since.

Courtly love in medieval Europe was virtuous love that emphasized nobility and...

The crown made for the wedding of Anne of Bohemia and Richard...

In part to escape the drudgery of daily life, (anyone know the feeling?) medieval fantasy life centered around love. And not just any love — chivalric love. The greatest knight wasn’t just a warrior, he was kind, courteous and devoted to his lady. This was the era that birthed the story of King Arthur and Knights of the Round Table.

Medieval heart brooch with three loops for (now-lost) pendants. The reverse is...

A wolf-tooth set in a heart-shaped bezel. The ring is inscribed with...

it is also the era of Geoffrey Chaucer (and when we begin inching toward Valentine’s Day). In 1382, after five years of negotiations, Anne of Bohemia married Richard II of England. In honor of their marriage, Chaucer wrote a love poem titled “The Parliament of Fowls.” And in it, he mentions Valentine’s Day.

“For this was on Saint Valentine’s Day when every bird comes there to choose his match” — Parliament of Fowls, Chaucer, 1382

Chaucer wasn’t the only poet who associated Valentine’s Day with love. French poet Oton de Grandson composed “Saint Valentine's Dream.” All this talk of hearts and love contributed to a sudden proliferation of hearts — on books (even heart-shaped books!), on tapestries, and, of course, heart-shaped jewelry.

Reverse of a gold brooch, inscribed in Medieval French "Ours and always...

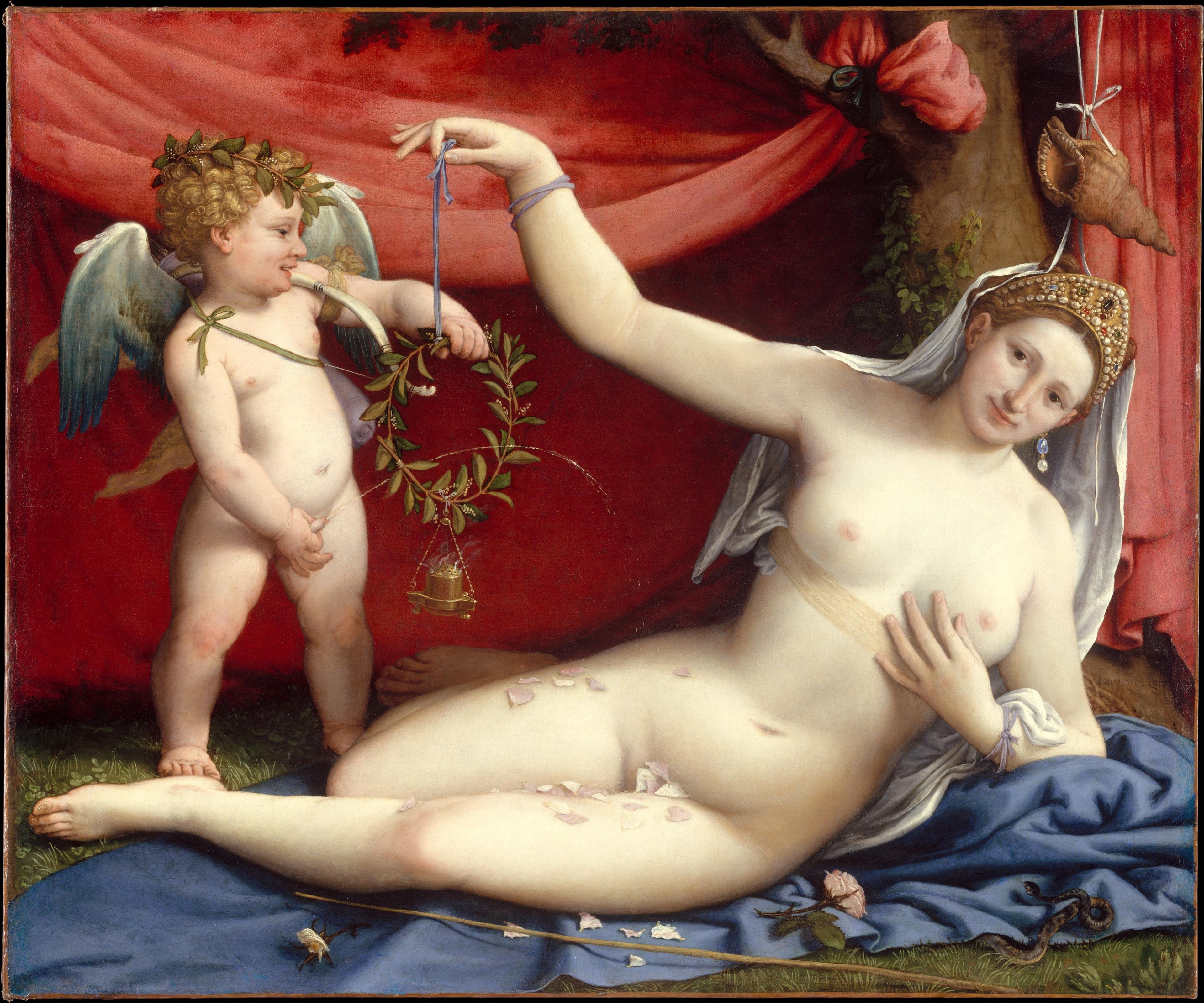

A painting to celebrate a Renaissance marriage depicts a naughty Cupid peeing...

Catholics didn't leave the heart to the Protestants. During the Counter-reformation, they...

during the renaissance,Cupid, that mischievous son of Venus, supplanted the heart as the love symbol of the day. However, our favorite symbol never completely disappeared. It would appear now and again (particularly in Catholic iconography), but Cupid definitely pushed the heart shape to the margins.

Martin Luther's seal — a.k.a. the Lutheran rose — with its red...

Then, in the 16th century, Martin Luther revived the heart, by incorporating it into his personal seal. With his nod of approval, the heart was one of the few icons acceptable in Protestant and Calvinist circles. Now, the heart icon could equal religious as well as amorous love.

Silver heart-shaped brooch, inscribed, "Love" on the reverse. In the late 1800s,...

When the heart's tail curves to the right, it's known as a...

While Martin Luther was fighting for the heart symbol in Germany, in 16th century Scotland, a silver open heart-shaped brooch had become a common betrothal gift. Then, after the couple married and had a child, the brooch would be pinned to the baby's clothes to ward off witches or even worse, some evil fairies who might steal the baby and switch it out (this was known as a changeling. Yikes!)

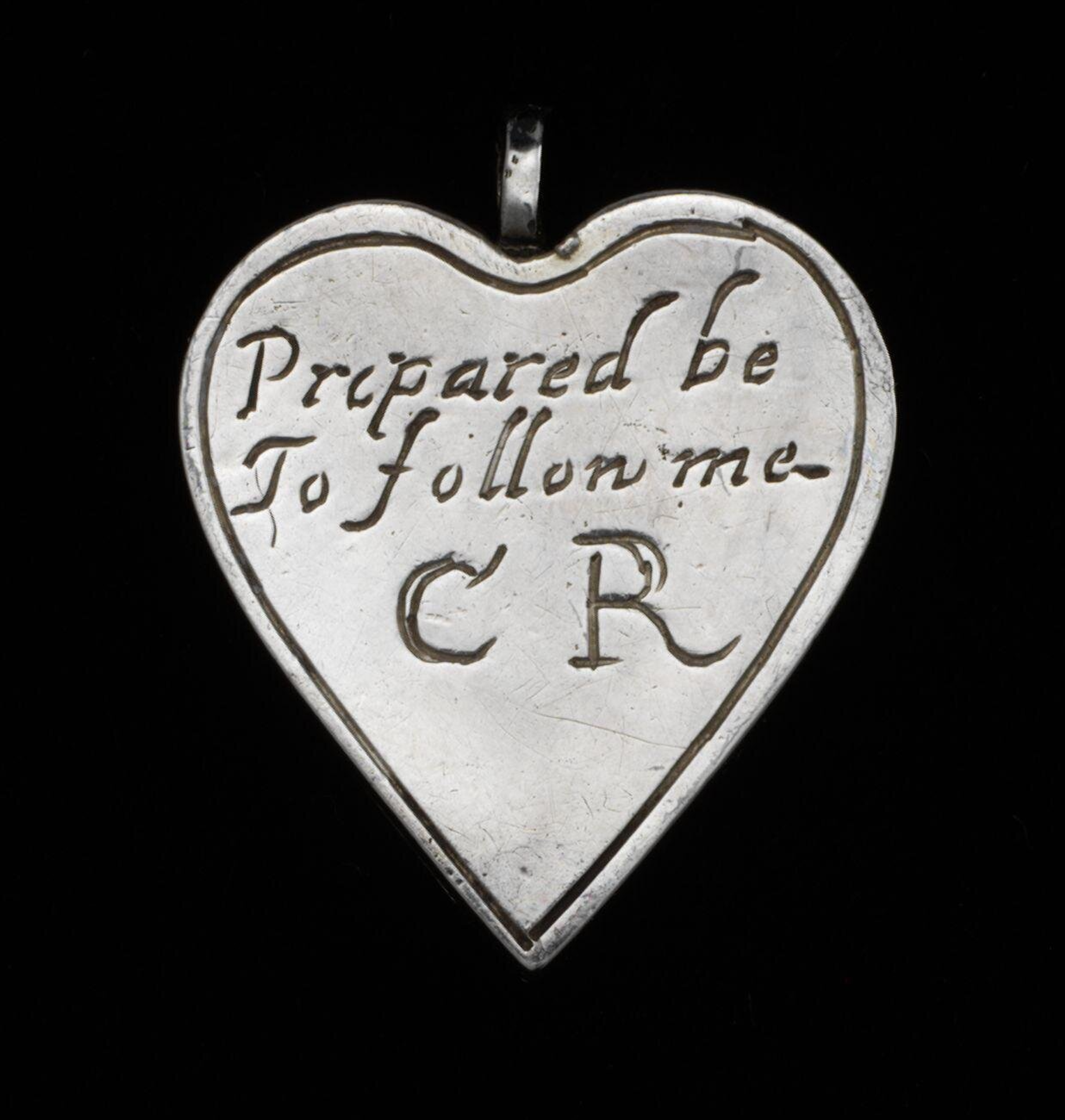

A loyal heart. Following the execution of Charles I in 1649, commemorative...

Reverse of the heart in support of Charles I, 1649. Victoria &...

In 1741, the London Foundling Hospital was established to care for the...

By the 18th century, the heart had become the established symbol for all kinds of love. And every form of the heart was popular: asymmetrical witches hearts, blazing hearts, twin hearts (love intertwined), hearts with crowns (loyalty), stout hearts, narrow hearts, hearts surrounded by pearls (you are beautiful), hearts with arrows (love conquers all).

A "secret picture" of Queen Victoria painted as a gift for husband...

A heart-shaped locket containing Prince Albert's hair when he was a child...

And in the 19th century, jewelry loving Queen Victoria kept the heart trend front-and-center. She loved jewelry with some sentimentality and the heart fit that bill perfectly. She had numerous heart-shaped jewels including a charm bracelet with enameled heart lockets, each containing the hair of one of her children. Heart jewelry was a constant for the Queen. She wore during both the happy periods of her life and during mourning.

Queen Victoria’s royal stamp of approval made the heart one of the most popular motifs of the Victorian age.

Onyx heart with the name of Queen Victoria's daughter Alice (who died...

Reverse of the locket, which holds a lock of Alice's hair. The...

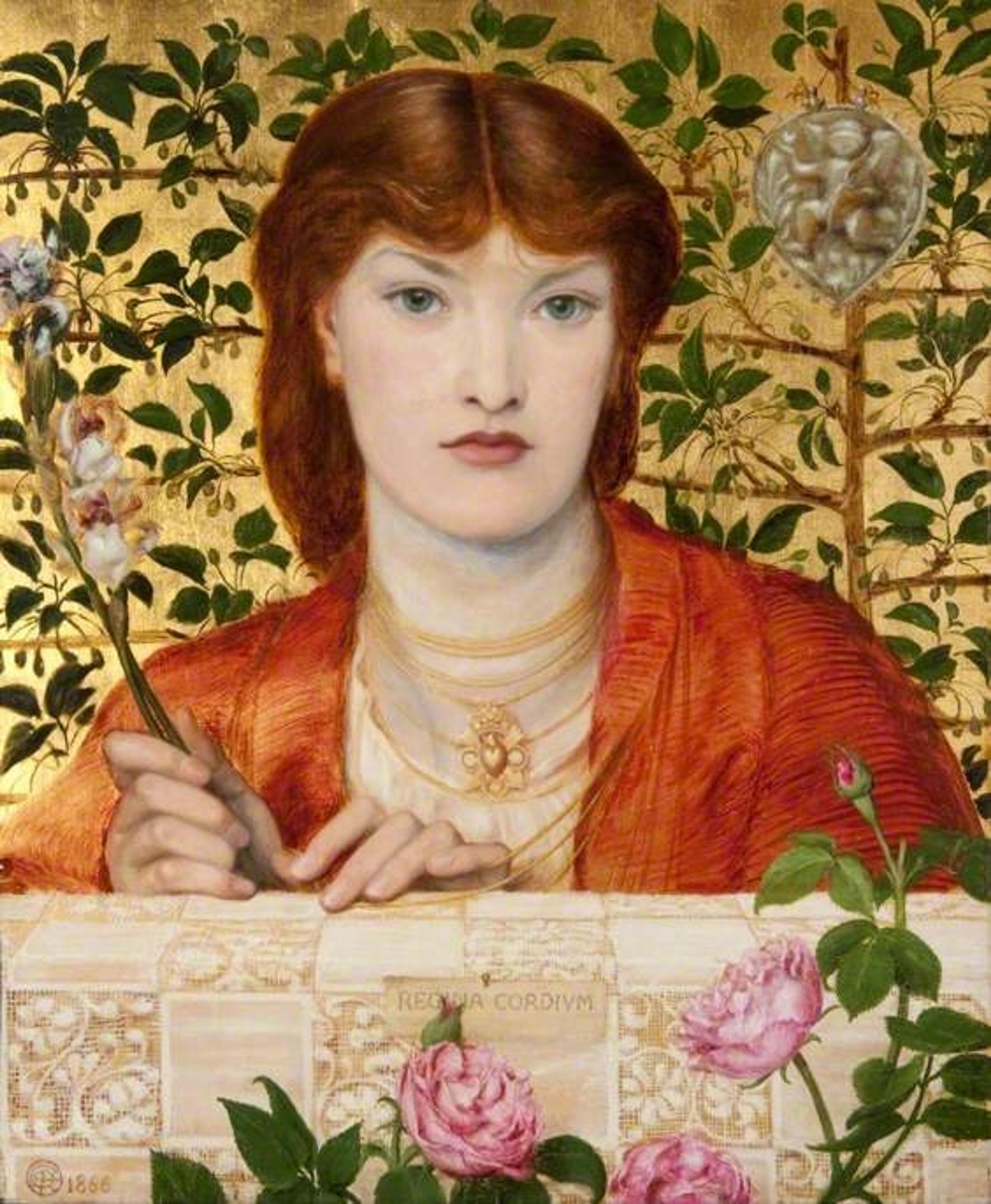

The same heart-shaped necklace in two Rossetti portraits. Monna Pomona by Dante...

Regina Cordium by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, 1866. The Glasgow Museum.

Arts and Crafts artists may have eschewed Victorian industrialism but they certainly embraced the heart motif. After all, they were into all things medieval, and that certainly included the heart. Basically, everyone in the 19th century — no matter their political views or status — was into the heart-shape. And our obsession with the heart continues to this day.

This paste-set heart brooch was given to Jane Morris (wife of William...

A portrait of Dante Gabriel Rossetti's mistress, Fanny Cornforth. Fanny is wearing...

let’s circle back to Chaucer’s Valentine’s day. The holiday, with all its emphasis on the heart-shape, had been a well-established since the 17th century. In Britain, the gift-giving frenzy could last as long as a week — making it an upper class holiday. But by the 18th century, handmade cards, sealed with wax, and left on a lady’s doorstep was a thing everyone could get into. And they did.

The earliestmass-produced Valentine’s was the brainchild of a female entrepreneur, Esther Howland of Worcester Massachusetts who, in 1847, designed her own cards and then supervised a team of girls who executed their construction. (She earned as much as $100,000 in a single year!) The availability of mass-produced cards crushed the hand-made versions. Even though, the mass-produced took over, when you send a Valentine, you are following a centuries long tradition. One that began with the feast of St. Valentine in 5 A.D. — not a Hallmark (established 1910) holiday at all.

An Esther Howland Valentine's card. "Affection" ca. 1870.