Container jewelry— tiny vessels meant to house some other token — had been around long before what we know as lockets. The first “lockets” might hold medicinal herbs, religious relics, prayers or perfumes. This early Egyptian example of the style probably contained substances believed to be magical.

Hathor-headed crystal pendant, c. 743-712 BC.

Jewelry is the most convenient way to keep what’s important on you at all times. During the Black Plague, tiny perforated pomanders — aka lockets — held ambergris or other scented materials that people believed (hoped!) would keep them safe from disease. Since it was believed that one could contract the disease by breathing in contaminated air, doctors advised their patients to carry nice-smelling things with them to dispel the odor of the plague.

One of the earliest known examples of a sentimental locket belonged to Queen Elizabeth I. The ring, dated 1575, included a miniature portrait of herself and her mother Anne Boleyn in it. She’s said to have never taken it off.

Elizabeth I’s Chequer Ring.

The locket as we know it rose to popularity in the 1800s.

The earliest ones contained locks of a loved one’s hair, sometimes plain, sometimes woven into elaborate designs. These weren’t necessarily mourning pieces — many were purely sentimental. In a time before photography, a lock of hair may be all you had to remind you of your beloved when separated.

A heartbreaking practice was for parents to leave orphans with a locket when dropping them off at orphanages. Remember the broken half of a locket in “Annie”? That was based in truth.

A charter for the Foundling Hospital, a children’s home in London during the 1700s, stipulated that parents who came to drop off children children should “affix on each child some particular writing, or other distinguishing mark or token.” The token might be a message, or a small item like a ribbon, brooch or a locket. These tokens would help identify the child if the mother was ever able to return. So for centuries, lockets have used as signifiers of hope, heritage and remembrance.

Still from Annie, 1982.

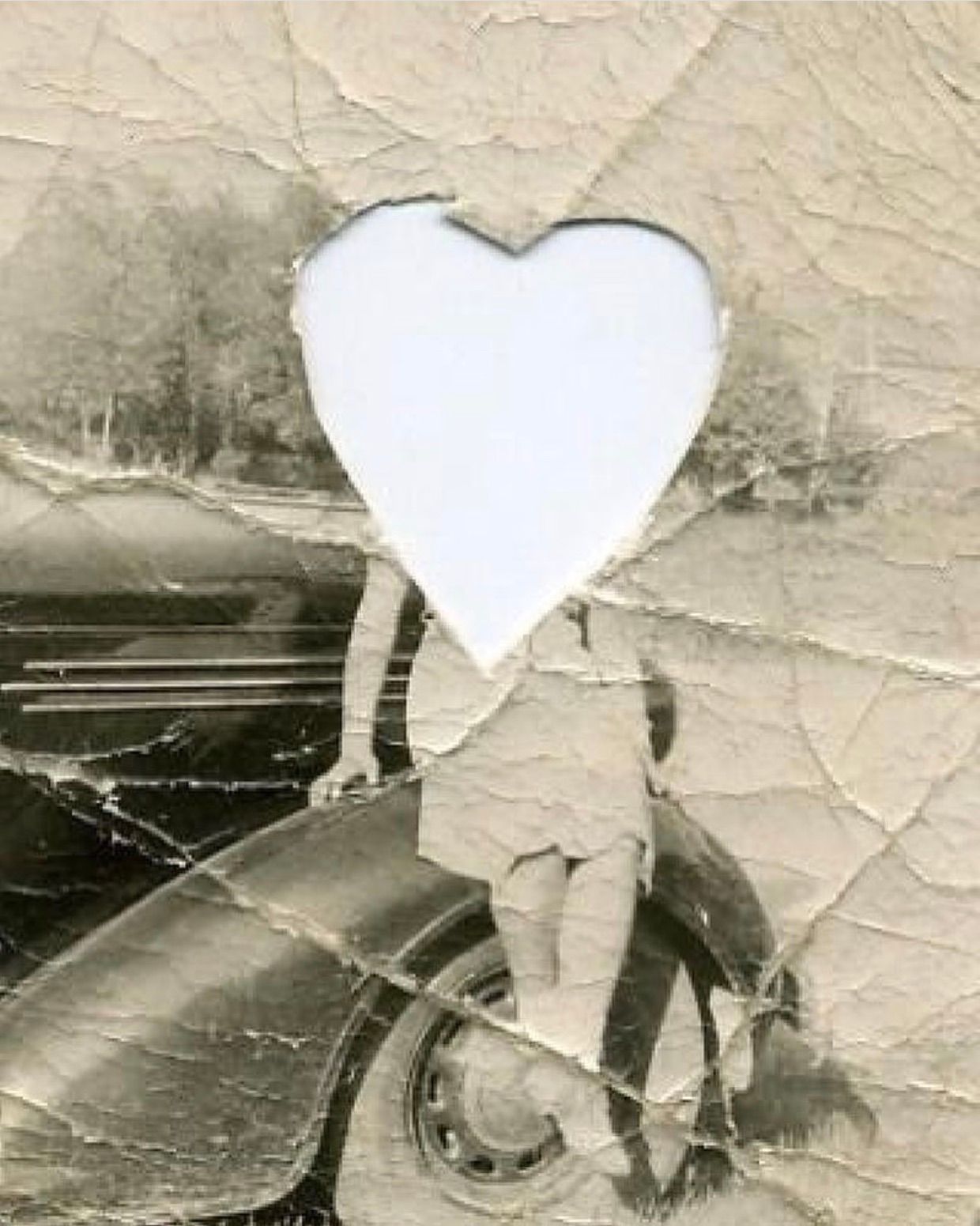

The invention of photography changed the world, and lockets evolved with the new technology. Shortly after the first photographic images were developed, everyone wanted a portrait. Ambrotypes came first — these were images printed on glass. Next up were tintypes, on tiny pieces of iron, which could be cut out and put inside a pocket, a little leather-bound book made for the purpose, or a locket. It helped that tintype cameras were relatively portable — enterprising photographers during the late 19th century would set up shop at county fairs and on boardwalks, offering cheap portraits while the customer waited. Photography was for everyone.

1860s Tintypes and albumen silver prints in brass, glass and shell enclosures....

In the US, lockets gained popularity during the Civil War, when soldiers gave them to their sweethearts as a memento in case they didn’t return home. The Industrial Revolution allowed people from most social classes to buy mass produced lockets, which became the perfect receptacles for photographs. The practice of soldiers gifting lockets to their loved ones continued through World War I & II. The tradition was so common that lockets were even sold at post offices.

To this day, the desire to keep loved ones close to our heart endures.