Ancient cultures throughout the world constructed pearl origin stories that centered on the divine. Ancient Chinese scholars believed pearls originated in the brain of a dragon. In Indian mythology, they were formed in celestial water droplets. Middle Eastern philosophers believed they formed from from the tears of gods. The Byzantines spoke of pearls as possessing their own source of light, a miraculous remnant of the lighting bolt that was thought to have penetrated the oyster’s shell during creation.

This style, popular in ancient Rome, were known as “crotalia” (from the...

Byzantine bracelet (one of a pair), made in Constantinople, 500-700, Metropolitan Museum...

Those mythical creation stories imbued pearls with perceived supernatural powers. And early humans coveted pearls not for their monetary value, but for the gem’s abilities. Pearls were thought to bring vitality to the wearer, and they had mood ring status — it was believed that the pearl clouded when the wearer was sick and would lose all luster when the owner died.

Even as pearls became economically significant, they retained their mythical status.

Romans depicted the martial bond between Cupid and Psyche as a strand...

Head of Venus, c. 100, The J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu, California

Roman emperors adored pearls — the more, the better. The emperor Caligula wore shoes encrusted with pearls and decorated his favorite horse with a pearl necklace. Pearls were an important component to Roman pagan religion and were often dedicated to Venus, the goddess of love and beauty, who according to mythology, emerged from a shell. When Emperor Alexander Severus received a gift of two pearls intended for the Empress, he hung them instead on a statue of Venus. Julius Caesar enacted sumptuary laws that forbade wearing pearls if a citizen was below a certain rank.

According to Pliny (Historia Naturalis) “a pearl worn by a woman is as good as a [herald] walking in front of her."

Detail from The Banquet of Cleopatra, 1653 by Jacob Jordaens. Hermitage Museum,...

Figurine of Capitoline Aphrodite with pearl earrings, Late Hellenistic or Roman Imperial...

In one of the most legendary ancient pearl stories, Cleopatra bet Marc Antony that she could consume the value of an entire country in a single meal. After a sumptuous dinner, Marc Antony was certain he had won. The food had been opulent, but certainly not worth the value of an entire country. Then Cleopatra asked for dessert to be served, and a glass of vinegar was brought to her. She removed a pearl from one of her earrings and dropped it into the vinegar. The pearl dissolved into a slush that Cleopatra drank. That single pearl was worth 30 million sesterces (more than $14 million dollars). The other pearl was cut in half to hang from the statue of Venus in the Pantheon.

Eleonora di Toledo, 16th century. Member of the Spanish royal family during...

Detail from Portrait of a Lady in Allegorical Guise by Pierre Mignard,...

Fast forward to 1492, when King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain commissioned Christopher Columbus to find a direct route to India — the source of spices, gems, fabrics and pearls. Columbus, as we know, never reached India, but on his third trip to the Americas in 1498, he stumbled upon the pearl fisheries of Central America. He returned to Spain with 50 ounces of pearls.

Portrait of a Lady, probably Camilla Martelli de’Medici by Alessandro Allori, c....

Eleonora (‘Dianora’) di Don Garzia di Toledo di Pietro de’Medici by Alessandro...

The knowledge (and exploitation) of those New World fisheries set off a pearl rush that historians would call the Pearl Age.

Monarchs throughout Europe filled their treasuries with vast quantities of pearls. However, no one was quite as obsessed as Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603). She had three thousand pearled gowns, pearled wigs, and of course, pearl jewelry.

Even the ermine is wearing pearls in this portrait of pearl-bedecked Queen...

Pearls in A Collector’s Cabinet by Johann Georg Hinz, 1664

In an effort to satisfy the European appetite for pearls, Spanish conquistadors hunted for pearl fisheries which they found on the islands off Venezuela in the Gulf of Panama and along Baja California. New World colonization was tied to pearl fisheries’ exploitation. Enslaved native pearl divers were forced to dive deep in dangerous waters. Thousands of enslaved divers were killed by shark attacks, hemorrhages and dysentery. To replace the divers killed, the Spanish raided neighboring villages to kidnap new slaves.

The mythological Tarquin preparing to rape Lucretia. Her broken pearl necklace foreshadows...

During the Pearl Age, pearls took on a dual meaning. They were seen as pure and godly, but the overwhelming pearl lust made them also a symbol of vanity and decadence. Paired with the fact that their mysterious aquatic origins gave them an erotic air — the pearl was irresistible.

Pearl earring topped with a gold cross that Charles I wore to...

Charles I wearing his pearl earring. His authoritarian rule partially caused the...

The Pearl Age ended in the 17th century due to wars, changing tastes and lack of supply.

The Pearl Age wasn’t going to last forever. During the Thirty Years War (a Protestant uprising, dating from 1618-1648, against Catholic oppression), the Civil Wars in England and peasant uprisings throughout Europe, the unrest and ensuing military spending siphoned much of Europe's pearl-buying dollars. For those who could still afford the bling, there was both faux pearls and new gemstone cutting methods which made other stones more appealing. The final nail in the coffin for the Pearl Age was the depletion of many of the world's pearl banks, which had been fished to exhaustion.

France's Empress Eugénie who shared Queen Victoria's passion for pearls. By Franz...

However, the pearl wasn’t down for the count. In the mid-1800s, new sources were discovered around Australia and South Pacific islands. Freshwater Scottish pearls had been known of since the 12th century, but had become inconsequential (and largely forgotten) by the 19th. Then in 1860, a German dealer traveling through Scotland found pearls in the possession of the local people. He bought all he could find and set off a storm of pearl fishing.

The sapphire clasps on the double-strand pearl necklace look to be the...

In her will, Queen Victoria left the diamond and pearl brooch to...

Victorians embraced pearls, which felt less ostentatious than colored gemstones and so appealed to the British upperclass for daytime wear. They were also “allowed” to be worn in mourning: Victorians believed that pearls represented tears. Queen Victoria had been a pearl fan even prior to the death of her beloved husband Prince Albert. She had been the recipient of pearl jewelry gifts designed by Albert, and she gave her daughters a single pearl at their birth and then added additional pearls at each birthday.

In 1861, when the Queen went into mourning, she fully embraced the tear symbolism of pearls and wore long strands for the rest of her life.

Maria Fyodorovna, born Princess Dagmar of Denmark, wife of Russian tsar Alexander...

Queen Alexandra (wife of Prince Albert and sister of Maria Fyodorovna) was...

In the 16th century, Venetian glass blowers developed a technique for creating iridescent glass. Then they adapted that technique to craft glass pearls by filling tiny iridescent bubbles with wax. That was the best anyone could do until the 17th century, when Monsieur Jacquin, a Parisian rosary maker, was watching his housekeeper scale a fish over a bowl of water and noticed how the fish scales dissolved in the water and created an iridescent liquid. He combined the fish scale liquid with varnish to create a lacquer. He named his invention “essence d’orient” and used it to coat the inside of a glass bead. The bead was then filled with wax and sold as a faux pearl.

His technique set off a flurry of experimentation and years of research yielded a formula that used the scales of 2,000 fish to produce just one liter of concentrated essence. Many faux pearl producers today still use Jacquin’s “essence d’orient” — either inside the bead, or they repeatedly dip the beads in the essence until a thick iridescent layer builds up.

Oyster shell with embedded pearl given to Queen Elizabeth II by the...

A chain of 177 Saxon pearls from the 18th century. They were...

Pearls are formed when a small parasite dies inside its shell (not a grain of sand). To soothe the irritation, the mussel or oyster secretes a substance called nacre to cover the parasite. Nacre is the same substance that coats the inside of a shell and gives it that iridescent color. (Fun fact: Nacre is today used as a biomaterial for bone implants). Pearls get larger the longer they remain in the shell — if you cut a natural pearl open, you can count the growth rings inside.

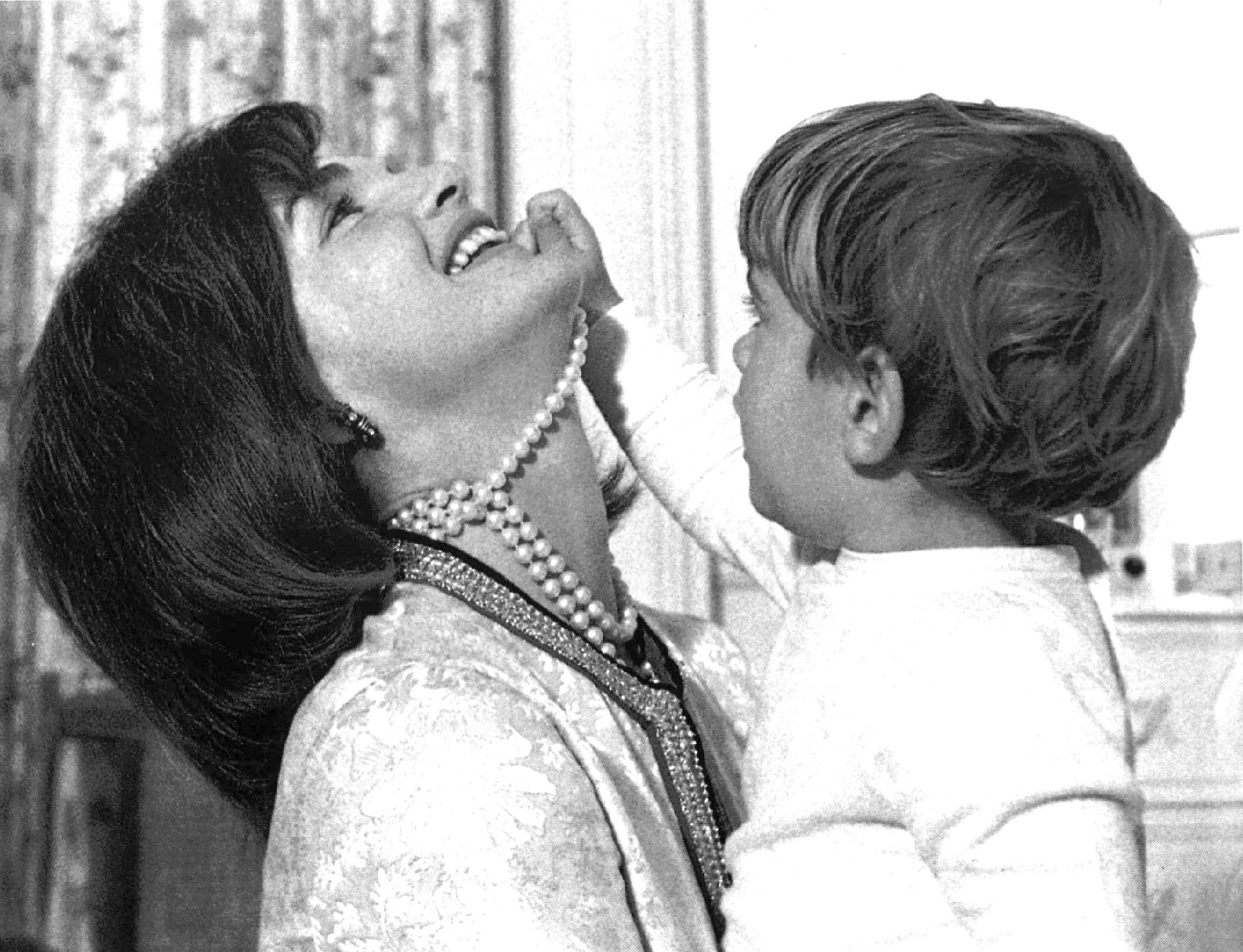

Wearing her faux pearls: First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy and John F. Kennedy...

There is one name in the world of cultured pearls: Mikimoto Kōkichi. Born in 1858, the son of a noodle-seller, he was fascinated by the local pearl divers (and even more so by the prices the pearls brought at the local market where the ground pearls were snapped up by Chinese buyers for medicinal uses.) He first started by selling the seed pearls that came from his area, but as supply seemed to be drying up, he began to experiment with pearl production. It would take him twelve years to hit on the method that is still used today. Making cultured pearls involves forcing a piece of polished shell into the oyster's reproductive organs.

Maud Allan in Vision of Salomé, c. 1908

An Elegant Beauty by William Clarke Wontner, 1920.

Throughout the 20th century, pearls adapted to the changing fashions. During the both the Art Nouveau and Arts and Crafts movements, jewelers used imperfectly shaped pearls to convey a natural, organic aesthetic. Then, in the Roaring Twenties, long pearl necklaces (known as pearl sautoirs) dangled down past the waist. Even during the Great Depression Hollywood films depicted stars like Mary Pickford in pearls. Post-World War II, pearls were critical to the over-the-top feminine look of the 1950s. Celebrities as with styles as different as Audrey Hepburn, Marilyn Monroe, and Jackie Kennedy were famous for their pearls. (Both Jackie Kennedy and Marilyn Monroe sported faux pearls.)

These days, the fashion for pearls have returned to the more gender-neutral status of the past. While female movie stars, Queen Elizabeth II and U.S. First Ladies (of all political persuasions) are photographed sporting pearl jewelry, they have competition from the gents. Harry Styles sported a Charles I-style drop pearl earring at the 2019 Met Gala and Atlanta Braves outfielder Joc Pederson wore a pearl necklace during the World Series. When the Braves won, his pearls were put on display at the Baseball Hall of Fame Museum in Cooperstown, New York.