Nicknamed “pinch” in the industry, pinchbeck was the most popular imitation gold in the 18th and early 19th century. The formula was developed by Christopher Pinchbeck, a London-based watchmaker who lived from about 1670 to 1732.

Print of Christopher Pinchbeck by John Faber Jr, c.1720-1750.

The true gold color of pinchbeck was achieved by combining copper and zinc — much less zinc than the combo of the same metals that is used to create brass. There is also some dispute about whether a gold wash was applied to the earliest examples, but Pinchbeck was notoriously secretive of his exact formula.

Pinchbeck’s biggest draw? It didn’t tarnish and fade like other gold alternatives at the time.

This new alloy was suited for those who couldn’t afford gold, or who didn’t want to risk taking their finest gems with them while traveling. Holdups at stagecoaches were a common occurrence. Rich people sometimes referred to their pinchbeck as “travelling jewelries.” To a person in the mid-1800s — rich woman or highway robber — pinchbeck jewelry was indistinguishable from solid gold jewelry. Jewelers of the day treated both materials with the utmost care and skill, and combined both with fine gemstones to create the most fashionable styles available.

Still from Sofia Coppola’s 2006 movie “Marie Antoinette.”

William Powell Frith’s 1860 painting “Claude Duvall” depicting a famous French highwayman...

Pinchbeck and his descendants continued to make watches, clocks, jewelry, buckles — you name it — out of the alloy until the 1830s. Pinchbeck’s son, Christopher Jr., even made an astronomical clock for George III that’s in Buckingham palace to this day. Astronomical and musical clocks were kind of the Pinchbeck family’s thing.

A clock made by Christopher Pinchbeck, from the Royal Collection Trust.

Imitators came about, inevitably: some even tried to pass off their knock-off pinchbeck pieces as real gold, giving the alloy a bad name. At one point, “pinchbeck” became a synonym for “counterfeit,“ or “fake.”

By the mid 19th century, pinchbeck faded out of popularity. A newly patented technology, “rolled gold,” became one of the gold alternatives du jour. It’s still used today — you might know it as “gold fill.” This jewelry undergoes a mechanical bonding process that melts a thicker layer of gold on top of the base metal (silver or brass). By law, jewelry must contain 5% gold by weight to be categorized as “gold filled.” Here's the most confusing part: a gold filled jewelry piece will still sometimes be stamped with a karat number, but this is only for the coating. Gold fill is more durable than vermeil or gold plate — even with daily wear it can last 10 to 30 years, although the layer of gold will eventually wear off and the base metal underneath will be exposed. We use antique rolled gold chains as a component in our Charm Base Necklaces.

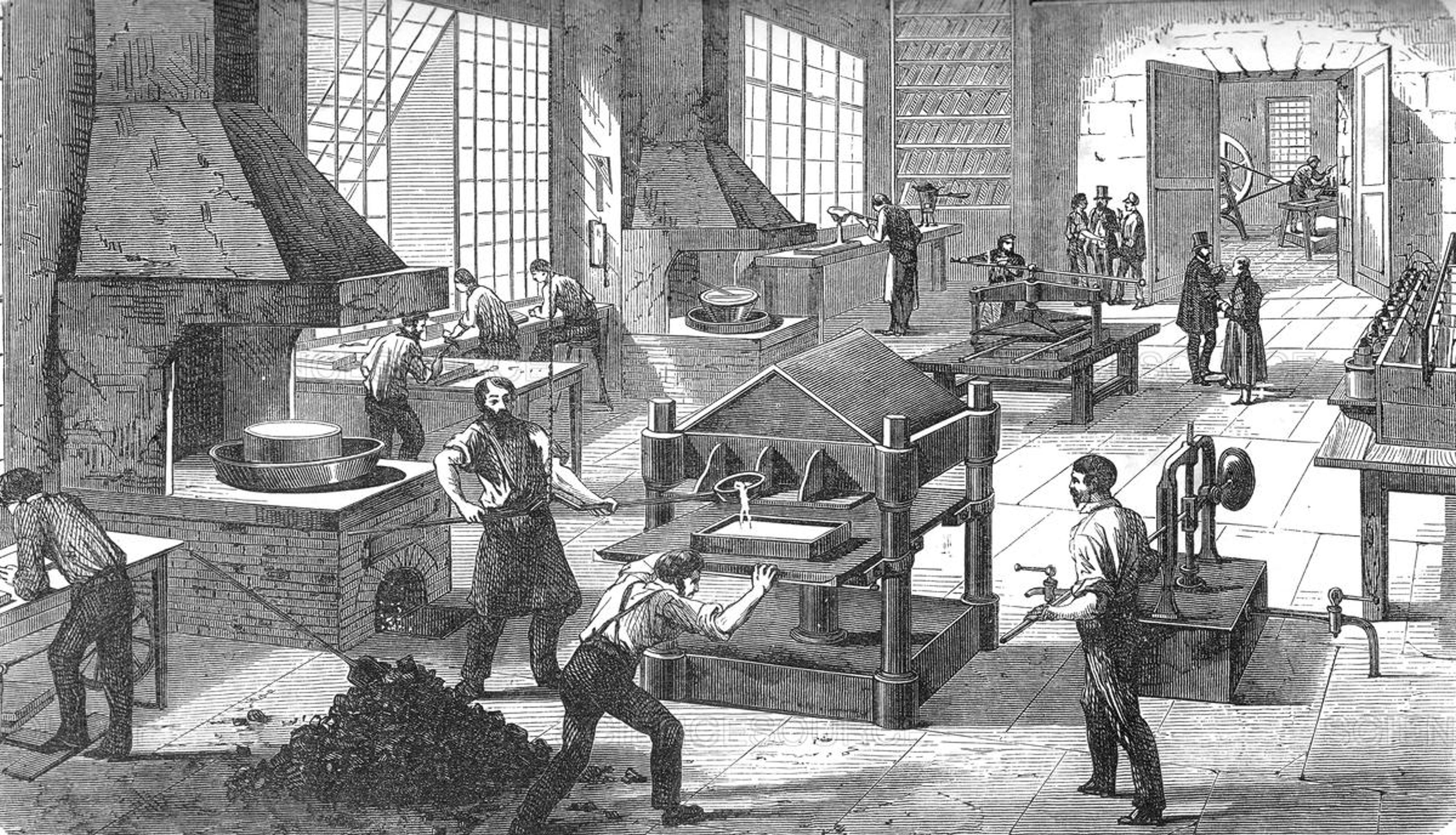

Gold plating, patented in 1840, was — and continues to be — another popular gold alternative. The process involves electrochemically depositing a layer of gold on a base metal, usually brass. The layer of gold is ultra-thin, thinner than “rolled gold” — the gold content is usually less than 1%.

A print of Luigi Valentino Brugnatelli, the Italian inventor credited to inventing...

Illustration of an Electroplating factory, 19th century.

And in 1854, 9 carat gold was legalized. Up until then, the UK assay offices only considered the purer 18k and 22k to be “gold,” and these would be stamped with an official hallmark. 9 carat gold has much less gold than the higher-numbered karats (37.5% pure gold, to be exact) and more other metals mixed in: zinc, copper, silver, etc.

Less gold = less expensive!

Another affordable alternative to gold? “Gold vermeil.” In the UK, it’s called silver gilt or gilded/gilt silver. It sounds fancier than “gold plate,” but it’s not so different. The gold layer is just a little thicker than gold plating, and the base layer is sterling silver, not brass. In time, the thin layer of gold can wear off.

Last of the confusing not-quite-solid-gold types: during the Edwardian era, “9ct front and back” showed up, usually in lockets. A layer of solid, heavy gold was applied to the front and back, but the inside parts — the glass frames, hinges, and interior parts — were brass, sometimes gold-plated, sometimes not. The benefit? Using this method allowed heavy engraving which would not be possible on rolled gold or gold plating. Yet you could still cheap out a little on the interior locket parts that you wouldn't normally see, or that would be covered by a photograph. Jewelry marked “9ct B & F,” “9ct Back & Front,” or just “Gold Back & Front,” was only produced over a short period of time, between about 1900 to about 1915.

Out of all of the gold alternatives, pinchbeck remains our favorite for its durability, historical quirkiness, and beauty. And luckily for us, while solid gold jewelry from the 18th and 19th century has been melted down and disassembled for the parts, pinchbeck has been quietly left alone. Now we get to collect it.

Detail: Viktor Bobrov, “Esther,” 1888.