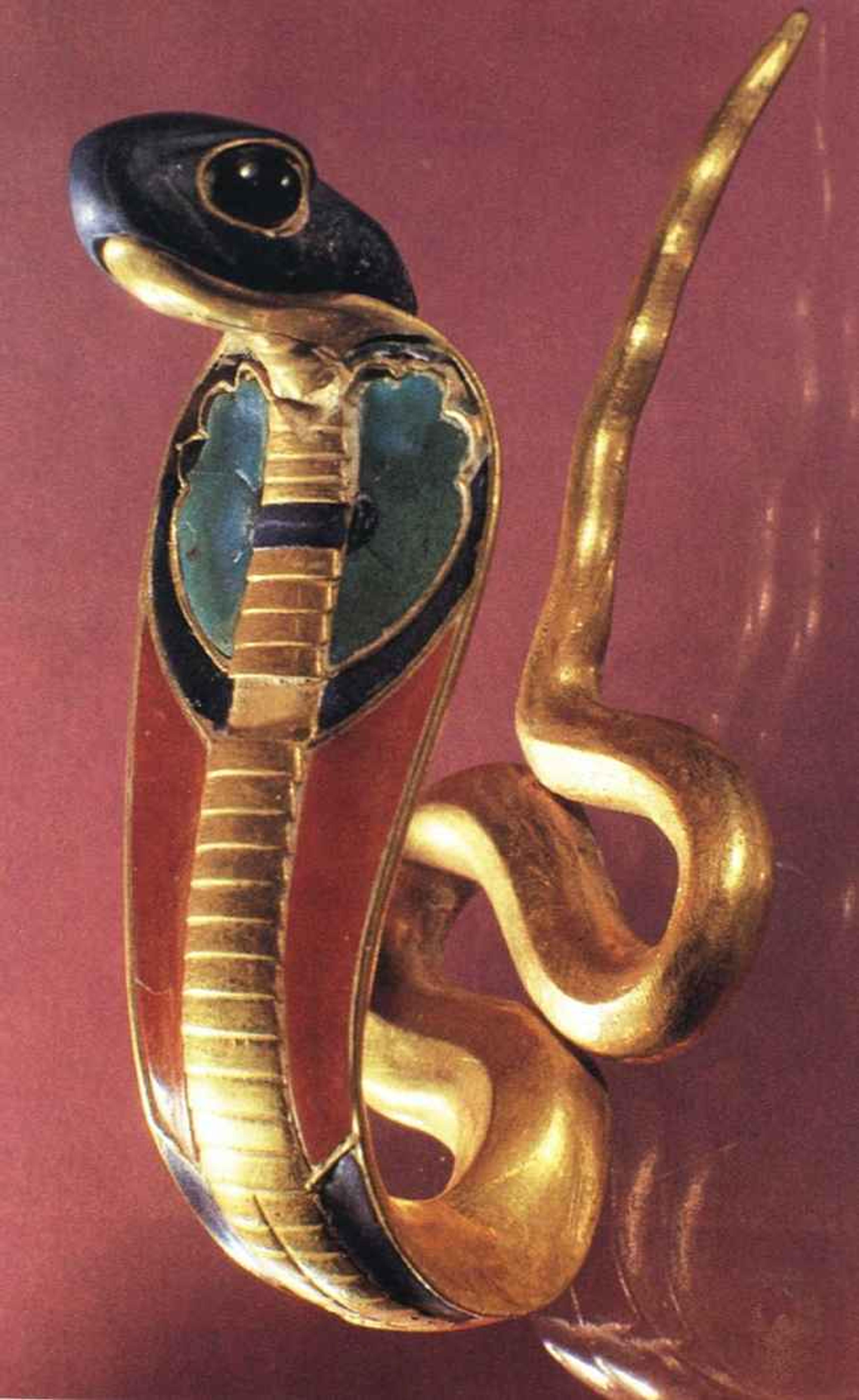

Ancient Greeks believed that spirits - in the form of snakes - guarded every structure, both man-made and natural. Egyptian Pharaohs wore headdresses with rearing cobras as a badge of divinity tasked with destroying enemies. Known as the Uraeus, they represented the serpent goddess Wadjet, one of the earliest Egyptian deities. She was the patroness of the Nile Delta and the protector of all of Lower Egypt. This cobra-crown served as identification of royalty, and signalled that Wadjet's power of defense was with the wearer.

Mummy Mask wearing snake bracelets, A.D. 60-70, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Lucrezia Borgia; Portrait of a Roman woman wearing snake jewelry, ca 1862-1866,...

In nearly every corner of the ancient world, snakes were protectors.

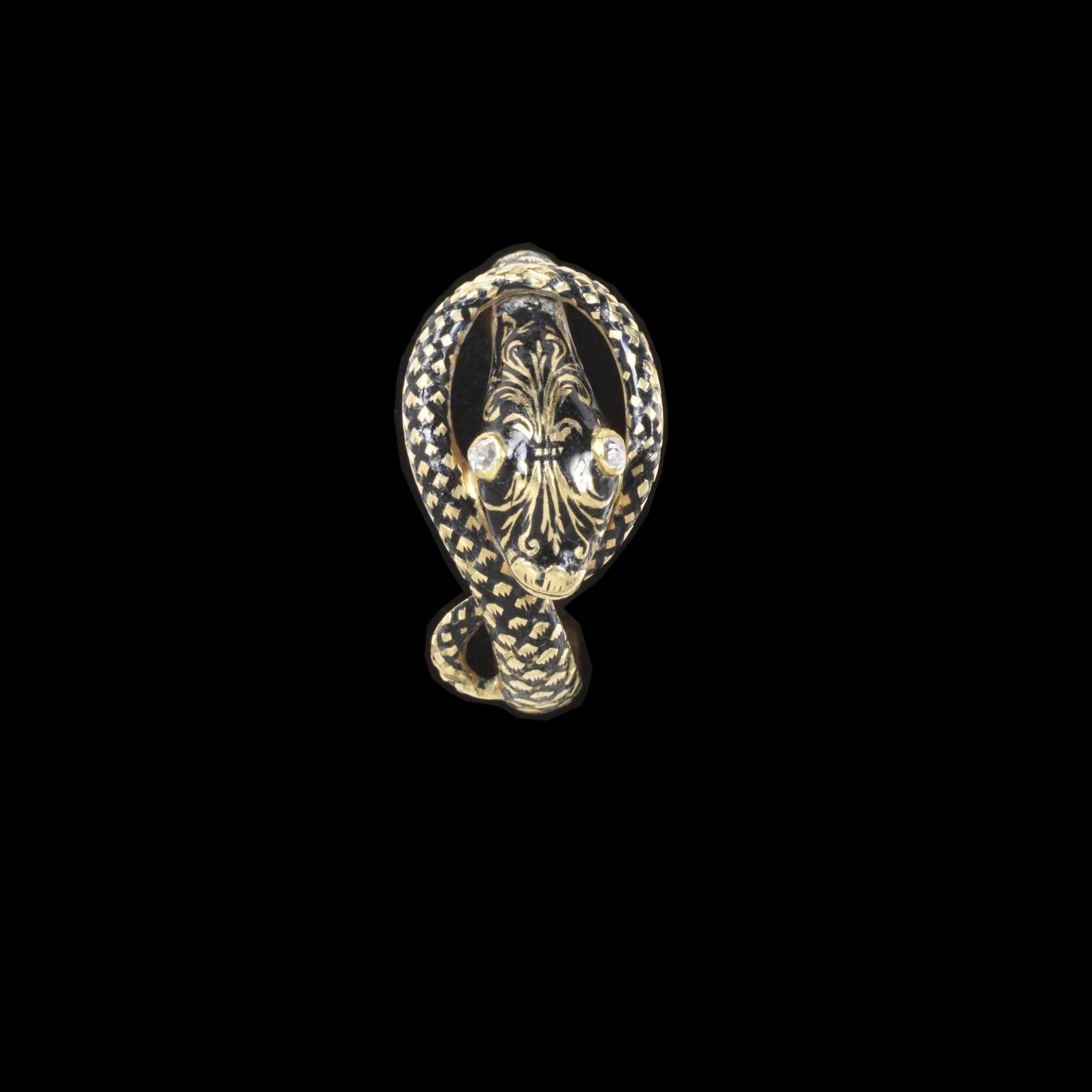

Golden Uraeus of Senusret II, ca. 1897 BCE - 1878 BCE. Prior...

Mask of Tutankhamun's mummy featuring a Uraeus. The cobra (Wadjet) with the...

Snakes were big in ancient Greece, too. They were sacred to Asclepius, the divine healer. In Greek mythology, when Zeus' wife Hera heard that her husband's mistress was pregnant, she flew into a jealous rage and sent two serpents to kill baby Hercules in his crib. Even as an infant, Hercules was unusually strong and he strangled the snakes before they could kill him. A knot with two interlocking loops was called a Hercules (Herakles) knot. The knot was a symbol of fertility, healing and love. Combined with the snake, it made a powerful amulet.

Hellenistic snake bracelet with a Hercules knot, 3rd century BC - 2nd...

Fresco: Young Heracles Strangles the Snakes, 60—79 CE. Pompeii, Archaeological Park, House...

In Ancient Rome, snake bracelets were worn with the serpent facing down, toward the wrist.

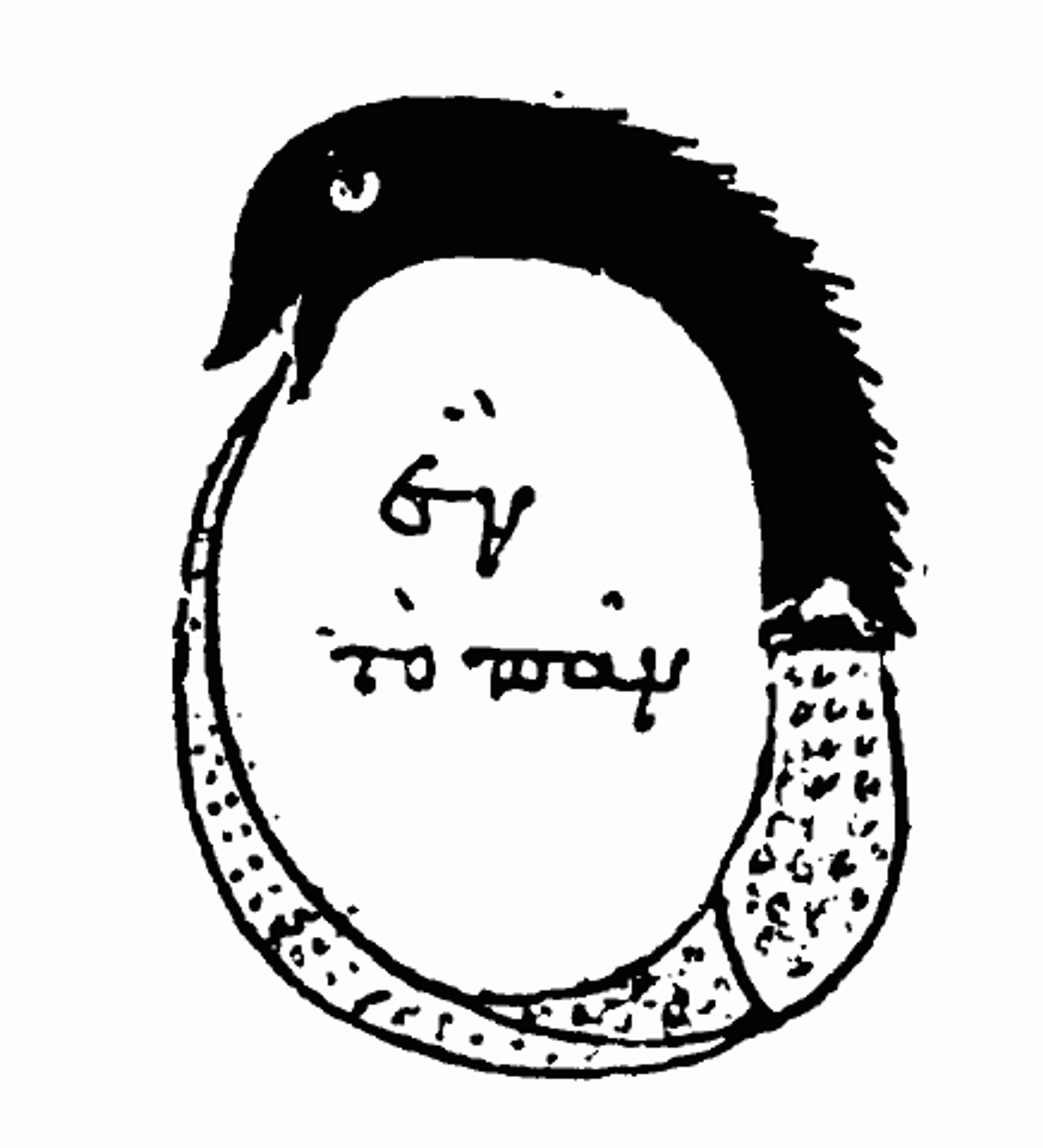

A recurring serpent motif throughout the past millennia is the ouroboros. The word means "tail-devourer" in Greek, and the image of a snake (or dragon) consuming its own tail represented the cyclical nature of life, and/or infinity. But the symbol is even older than the Greeks - the oldest known depiction of an ouroboros is engraved on King Tutankhamun's tomb. Eventually the symbol migrated around the world; during the Medieval period, the snake-eating-her-own tail became an emblem of alchemy, thanks to Cleopatra the (female!) alchemist. Her text - probably dating to the 3rd century in Alexandria - included this famous illustration with the words ἓν τὸ πᾶν ("The All is One").

Ouroboros illustration from the Chrysopoeia of Cleopatra

Detail, the second gilded shrine of Tutankhamun

The snake is the theriomorphic form of countless deities including Zeus, Apollo, Persephone, Hades, Isis, Kali and Shiva.

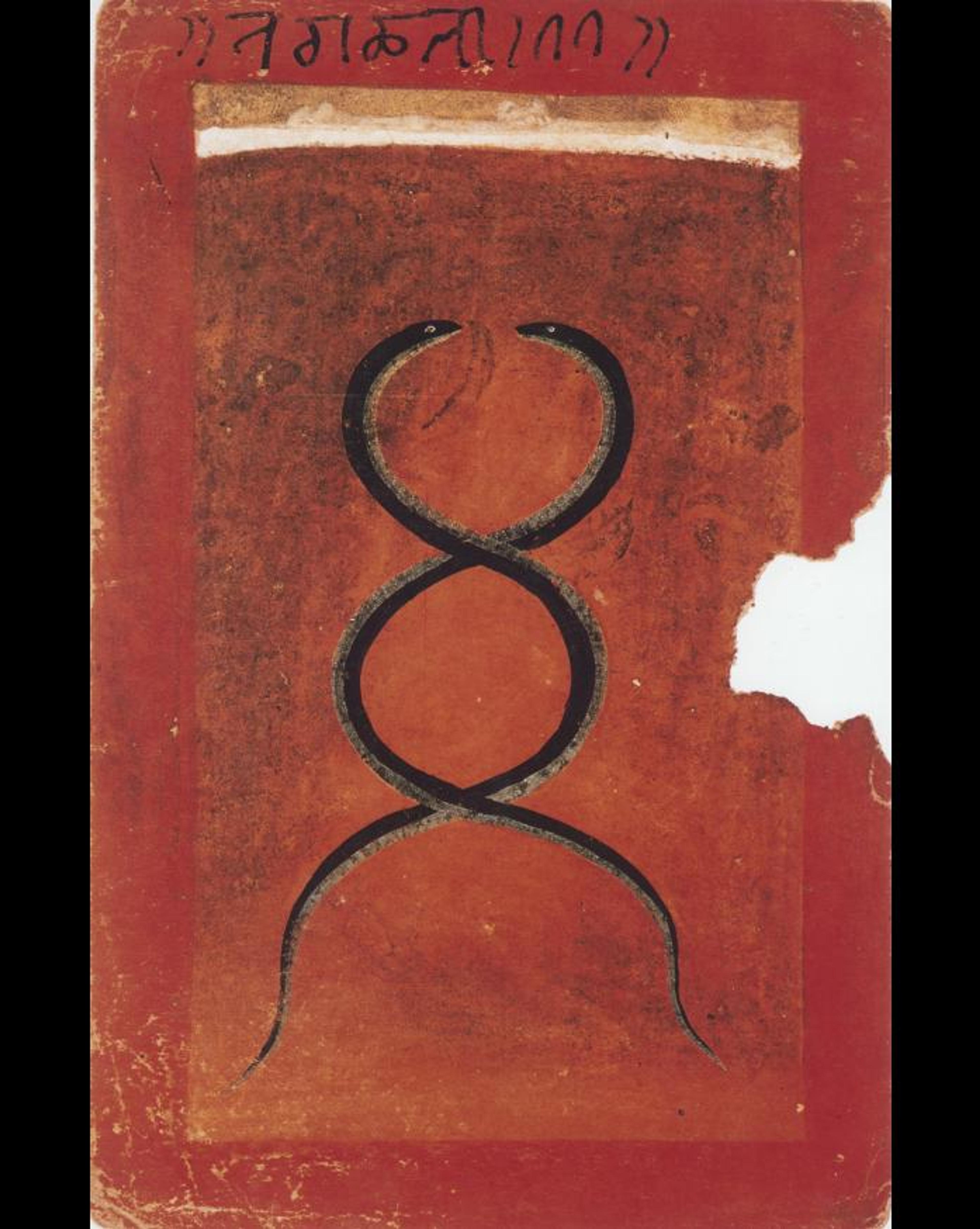

In the Tantric traditions of India, the feminine cosmic energy of the kundalini lies asleep like a coiled serpent at the base of the spine. Awakened through the process of yogic meditation, this serpent rises through the body, opening the energy centers or chakras to create an ecstatic, transcendent experience.

L’Envoûteuse (The Sorceress), Georges Merle (1883), Birmingham Museum of Art

A pair of intertwined serpents in the form of a yantra, or...

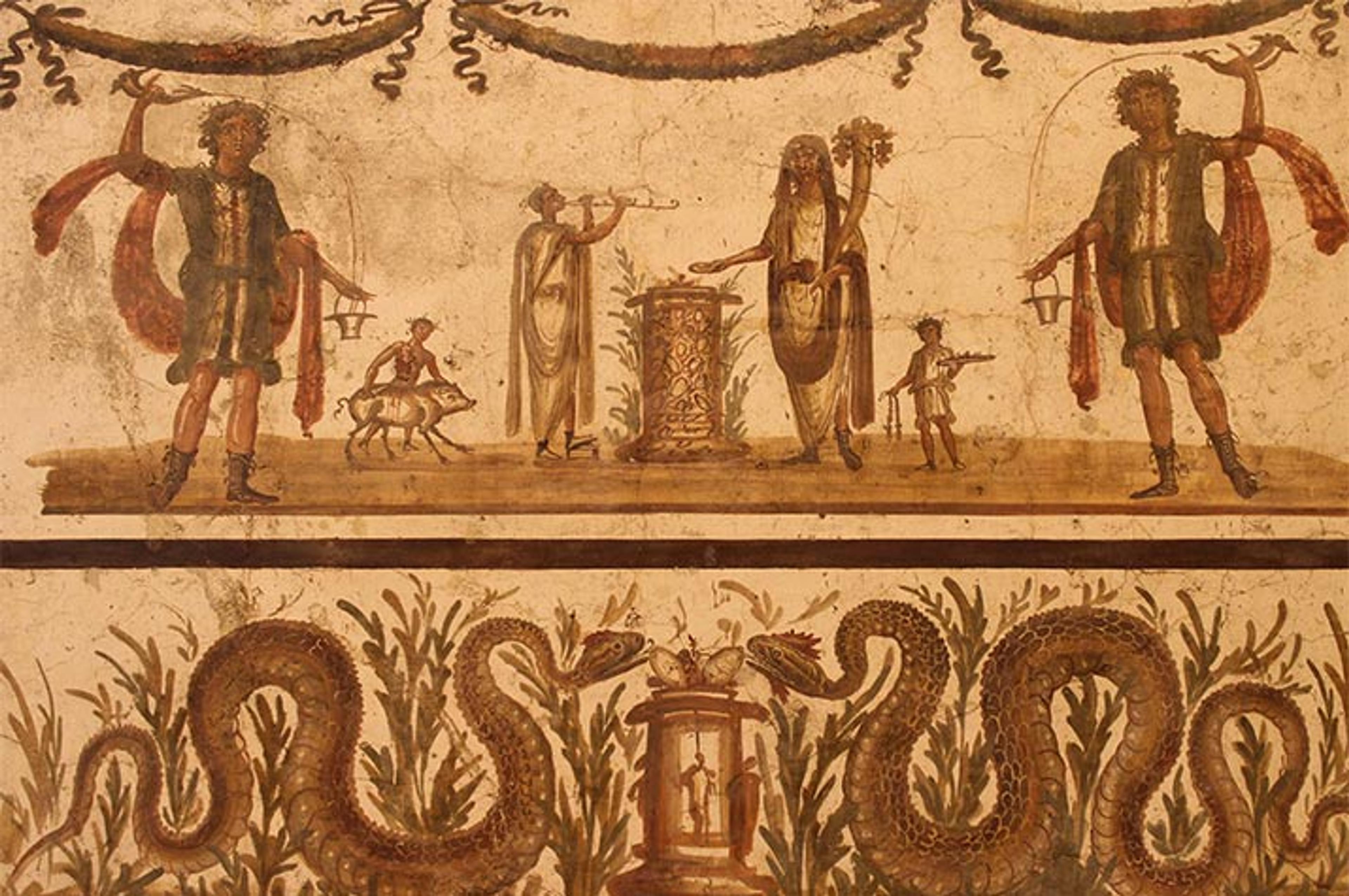

By the High Middle Ages (around 1000 A.D.), as Christianity spread through Western Europe, the serpent lost all nuance and became almost entirely associated with evil, the devil, and sexuality. But as the scientific reasoning of the Enlightenment took hold, witchcraft, magic and sorcery lost most of their power. And in the 1750s, excavations of the ancient Italian cities of Herculaneum and Pompeii captivated the world. Pompeii was filled with snakes - serpents decorated everything from household shrines to public temples. The demand for Greek and Roman inspired objects took Europe by storm, and suddenly snake jewelry was fashionable again.

Snakes as guardians appear in a lararium (household shrine). In these niches,...

Gold snake bracelet found at Pompeii, British Museum

By the 19th century, snake jewelry, already en vogue, received an even larger boost on the trend-o-meter. Queen Victoria was only eighteen when her uncle died in 1837, making her Queen. At her first council meeting, she wore a snake bracelet, hoping to channel the wisdom of the serpent. Then, to mark their engagement in 1839, Prince Albert gave Queen Victoria a ring shaped like a serpent set with small rubies, diamonds and an emerald (her birthstone). With that, the ultimate trendsetter of the 19th century sealed the fate of serpent jewelry.

There was a snake jewel for everyone. The aristocracy commissioned their serpent bracelets and rings from celebrated jewelers. Queen Victoria's daughter-in-law, Princess Alexandra, was rarely seen without some piece of snake jewelry. And working-class girls could imitate the look with a simple industrially manufactured snake ring in not-so-precious metals. The Ouroboros, with its naturally circular shape, was perfectly suited to be worn as bracelets, rings, and necklaces. And let's be honest, the pervy yet sexually repressed Victorians probably secretly loved the fact that a snake is an obvious phallic symbol.

The First Council of Queen Victoria, Sir David Wilkie, 1838

The cousins: Queen Victoria and Victoire, Duchesse de Nemours, 1852 by Franz...

Portrait of Alexandra, Queen Consort of the United Kingdom, Isaak Snowman, ca...

Grand Duchess Elena Pavlovna of Russia with her daughter, St. Petersburg, 1830,...

Twin snakes - two serpents knotted/entwined - became an especially popular motif in jewelry; the sentimental Victorians wore it to symbolize eternal love and endless devotion. This wasn't their invention, though - they were borrowing yet again from Classical culture. In Greek mythology, the caduceus is the symbol of Hermes. The god is often depicted holding a staff topped with two entwined snakes. The myth surrounding this symbol says that Hermes encountered two snakes wound around one another engaged in combat. The god separated the dueling snakes and established an accord between them - it follows that the symbol of entwined snakes came to represent not only the messenger of the gods, but also peace and unity.

Perhaps the lasting popularity of the snake was that it could symbolize so many things. What other symbol could claim to embody both love and death, sexuality and danger, healing and fertility? It was perfect for the death-fueled atmosphere of the 19th century when snake-themed mourning jewelry abounded. And for the romantics who loved the slightly sexy serpent as a symbol for endless love.

Wearing a snake bracelet, Emma of Waldeck and Pyrmont (Queen consort of...

Snake mourning ring, 1846, Victoria and Albert Museum

By the 20th century, all the major jewelry houses like Cartier, Bulgari and Boucheron had serpents in their collections.

“Don't forget the serpent...it should be on every finger and all wrists...the serpent is the motif of the hours in jewelry...we cannot see enough of them.” --Diana Vreeland, Vogue editor, 1968

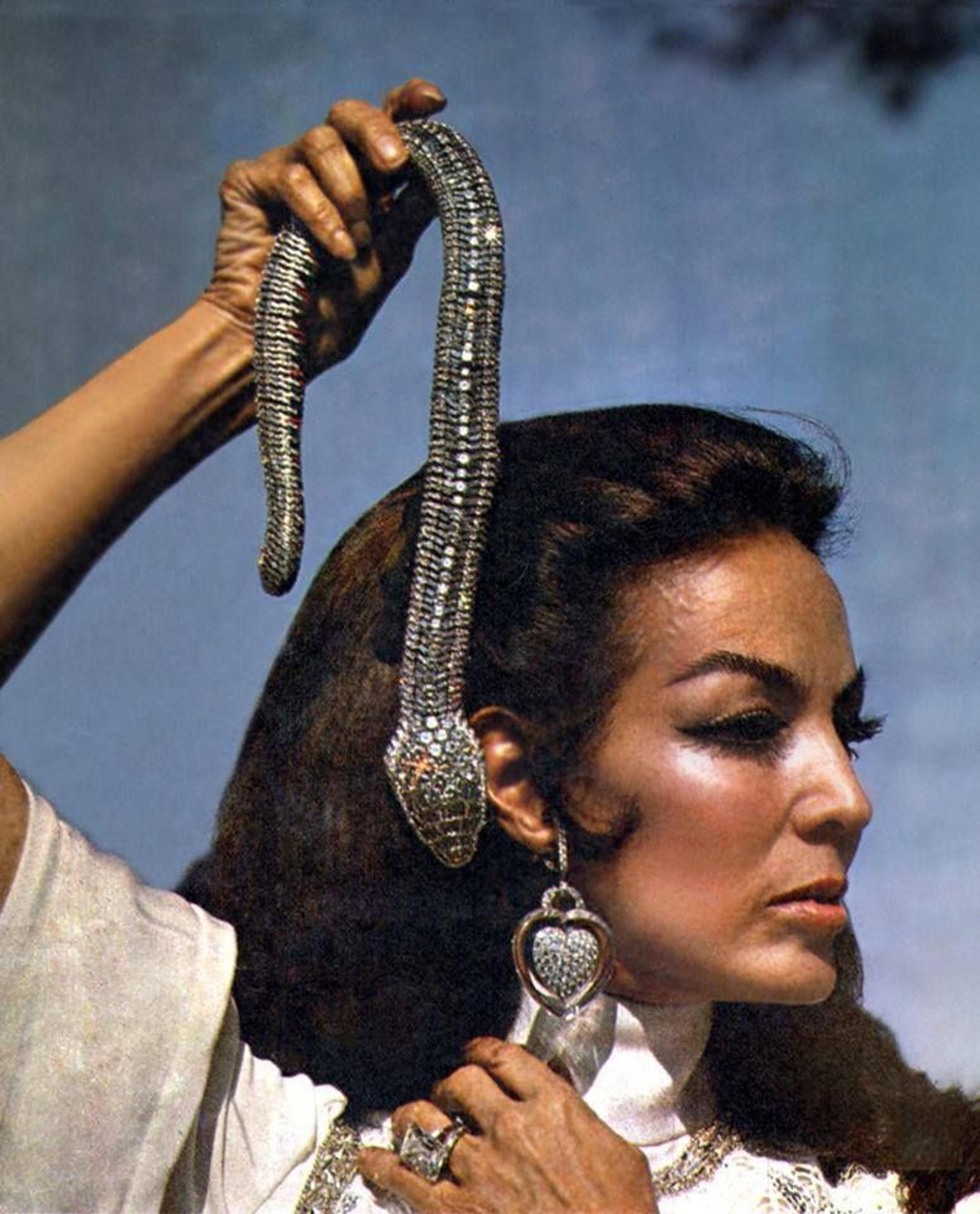

Mexican actress María Félix was arguably the greatest snake jewelry aficionado of the 20th century. In 1966, the actress was living in Paris with her third husband, Swiss businessman Alexander Berger. She already had quite the collection when she walked into the Cartier boutique in Paris and commissioned a snake necklace that could be draped around her neck like a real serpent. The fully articulated diamond-encrusted creature took two years to complete. María Félix was so pleased that she offered a champagne toast to all the Cartier craftsmen who worked on it and even commissioned a crocodile version a couple of years later. Both the snake and crocodile are now in the Cartier Collection.

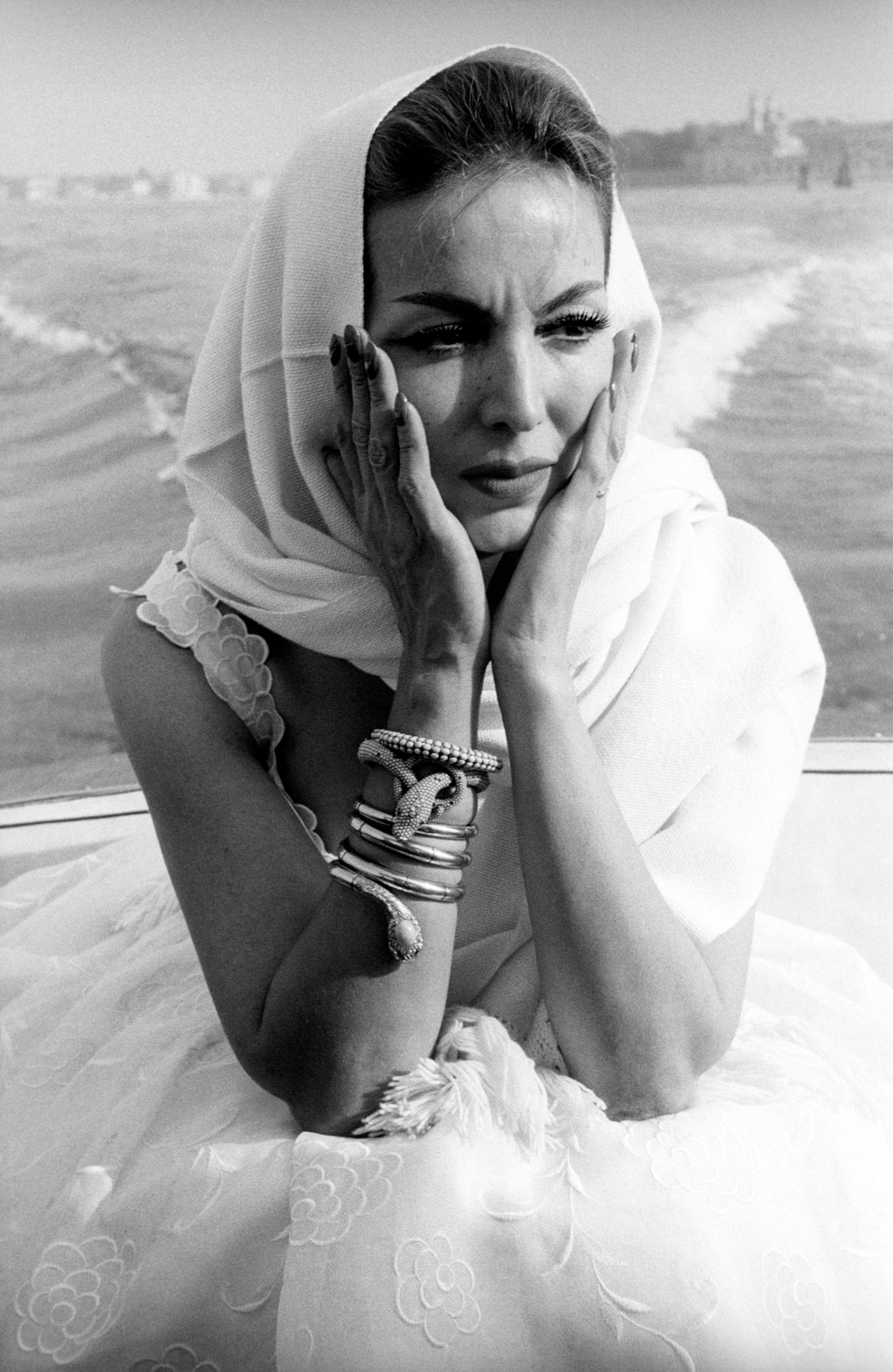

Mexican actress María Félix in Venice, 1959

María Félix holding her Cartier snake necklace with 2,473 diamond (178.21 carats)

In the modern world, the snake still reigns as a guardian, protector, and power symbol. The Zulu believe that every man is guarded by an ancestral spirit, an ihlozi, in the body of a snake. And in the Burkina Faso, pythons are revered as village guardians. Many in India welcome non-venomous snakes into their homes as harbingers of good fortune.