King Charles I ascended to the English throne in 1625 following the death of his father, King James I. He was a member of the Stuart family, whose dynasty would span the years between 1603-1714. (Fun fact: Princess Diana was a descendant of this royal clan.)

Engraving of Charles and his parents by Simon de Passe, 1612.

Portrait of King Charles 1 in his Robes of State by Van...

The ceiling painting at Whitehall Palace was commissioned by Charles to celebrate the idea of “divine right.”

“The Apotheosis of James I” by Rubens, 1633.

Like the entire Stuart dynasty before him, Charles believed in the divine right of kings. In simple terms, he was personally chosen by God to rule, so opposing him was a sin. As you can imagine, a lot of his subjects took issue with this.

Charles I and Henrietta Maria Holding a Laurel Wreath, 1632, by Van...

It didn't help that Charles married Henrietta Maria — a Catholic French princess — the same year he was crowned. This union offended his Protestant subjects, who didn't trust that the new king would keep his Catholic ideologies separate from politics.

During his reign, Charles reacted to political opposition by dissolving Parliament a number of times. After all, in his eyes it was his divine right. In 1629 Charles decided to rule completely without Parliament.

Parliament in the time of King Charles I. At this point, Parliament...

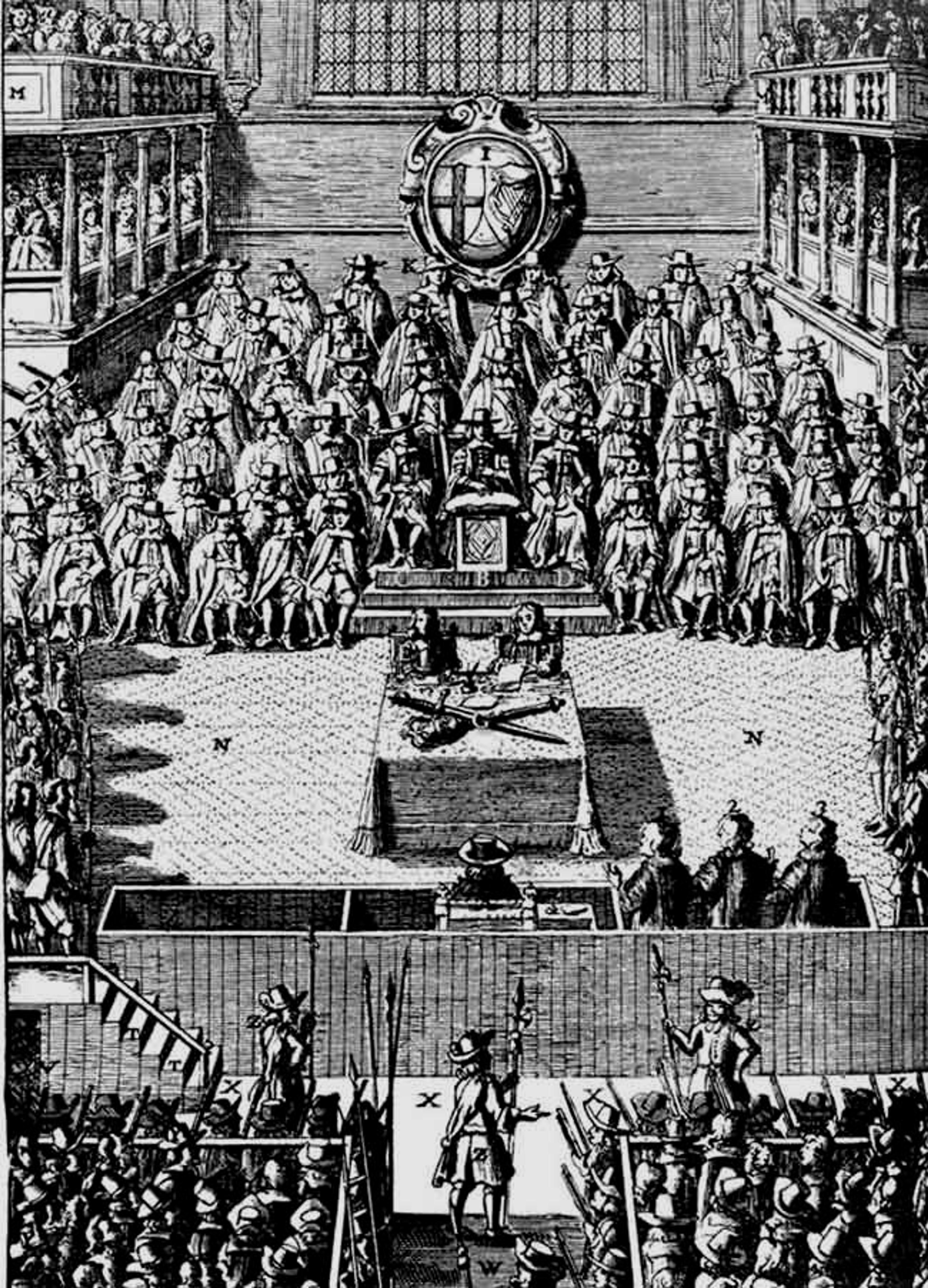

The Execution of Charles I.

The country was headed toward civil war, which finally broke out in 1642. After a bitter series of battles against the Parliamentarians and two more civil wars, the Royalist army was ultimately defeated and Charles was imprisoned. He was tried in court and beheaded for treason. His death shocked and fractured the nation.

Stuart crystal pendant c. 1650-1660, set with a watercolor portrait on vellum....

Ring, 1685-1705, in the collection of the V&A Museum. “CR” stands for...

Next up in power? Oliver Cromwell. Royalists endured serious oppression at his hands — many were exiled or worse. During these times showing support for the monarch was dangerous, so Stuart supporters found ways to show allegiance to the Stuarts through ciphered writing, literature, cultural resistance, underground networks, and jewelry.

All jeweled portraits would be set under flat-topped faceted rock crystal — ergo Stuart crystal.

Ring with face of Charles I, 17th c. painting, 18th c. setting....

An antique Stuart crystal ring in 18k. Inscribed W. Mc 1738. Via...

Though originally aligned with support of the monarchy, over time the style became more personal in nature. Later 17th century examples might not be related to Charles I at all. Different subject matter made of hair, gold cyphers, and colorful foil appeared under flat “Stuart crystal” with all sorts of other themes to celebrate a specific event. In general, a skull or skeleton + initials of the deceased = mourning jewelry.

The Charles I jewels were the first examples of mourning jewelry made to memorialize a specific individual. Before Stuart Crystal, Memento Mori jewelry had been popular. These skull / bones / gravedigger / skeleton themed pieces served to remind the wearer that death lurks around the corner, but in a more impersonal, universal way.

Gold Stuart crystal mourning slide, England, late 17th century. Image courtesy of...

High carat gold Stuart crystal mourning ring, c. 1680, from the EWJ...

Cupids, hearts and floral garlands usually signified the jewel was made for a betrothal or wedding. Portraits of aristocrats were popular, too.

Stuart crystal betrothal or wedding ring with hair, cupids and cypher, c....

Stuart crystal slide with hair, “EG” cypher and weird looking cupids holding...

Around 1730, the Stuart crystal style faded out in popularity. But the tradition of commemorating an individual's death — using hair, initials, painted portraits, inscribed names and dates — got more and more popular in the next centuries. The coming Industrial Revolution made it easier for most people, no matter what financial situation, to customize a piece of mourning jewelry to remember their loved ones.