How does one even begin to cut what is known as the hardest substance in the world? It’s taken thousands of years to answer that question. Before we examine, the types of diamond cuts, let’s look at the most famous diamond ever cut.

The Archduchess Christina of Austria by Martin van Meytens, 1765. Schönbrunn Palace.

Maria Josepha of Austria, 18th century. Hampel Auctions Archive.

Weighing more than 3,000 carats, the Cullinan Diamond is the largest gem-quality rough diamond ever found. It was discovered at the Cullinan mine in South Africa in 1905. It was put on exhibition in London and was visited by thousands of lookers, but no buyers. So the Transvaal Prime Minister (a region of South Africa, during a period when it was under direct British rule) suggested that the Colony buy it and give it to then King Edward VII. The King accepted it “for myself and my successors” and decreed that it be preserved as part of the Crown Jewels.

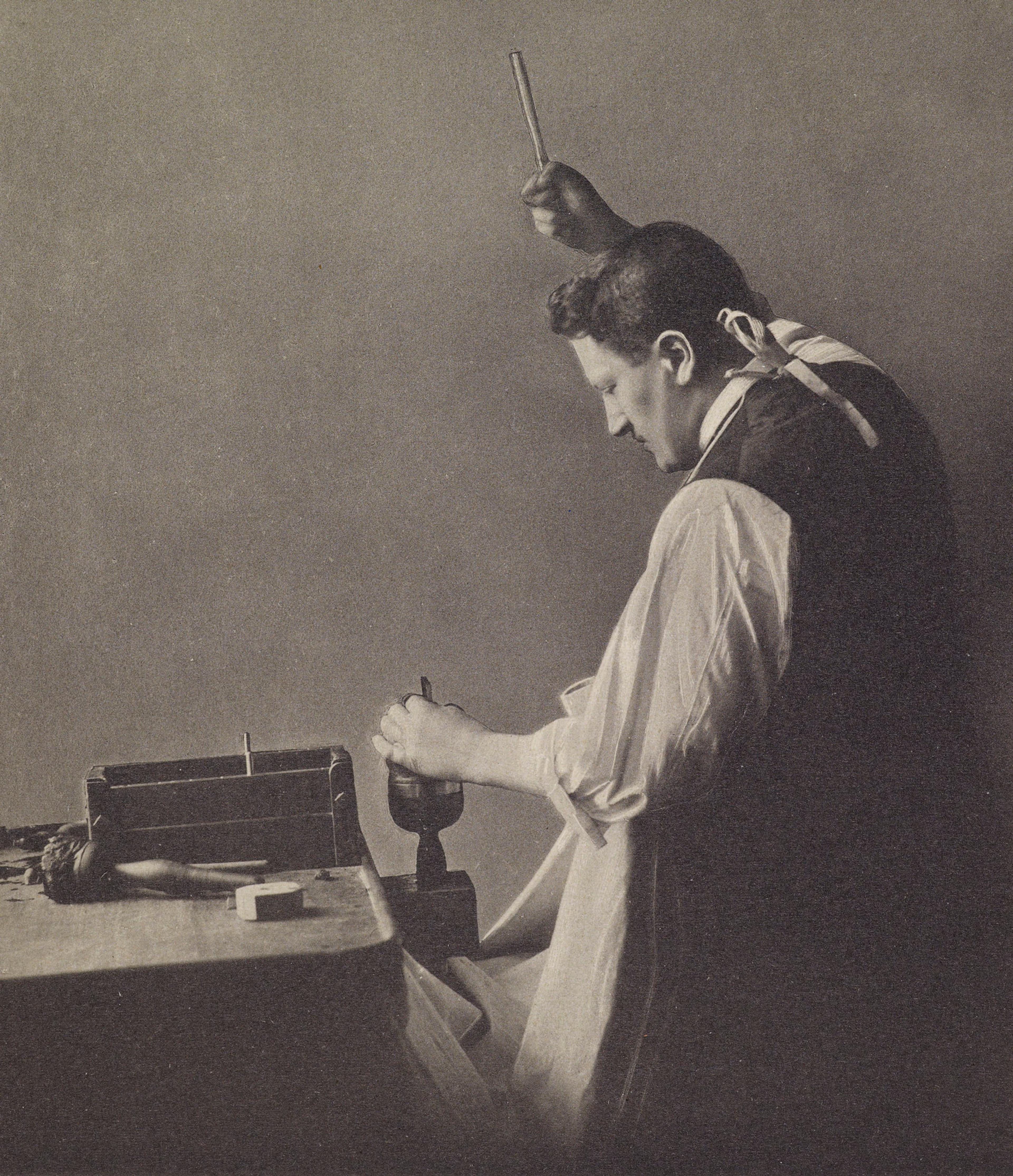

Mr Joseph Asscher preparing for the initial blow on the Cullinan Diamond,...

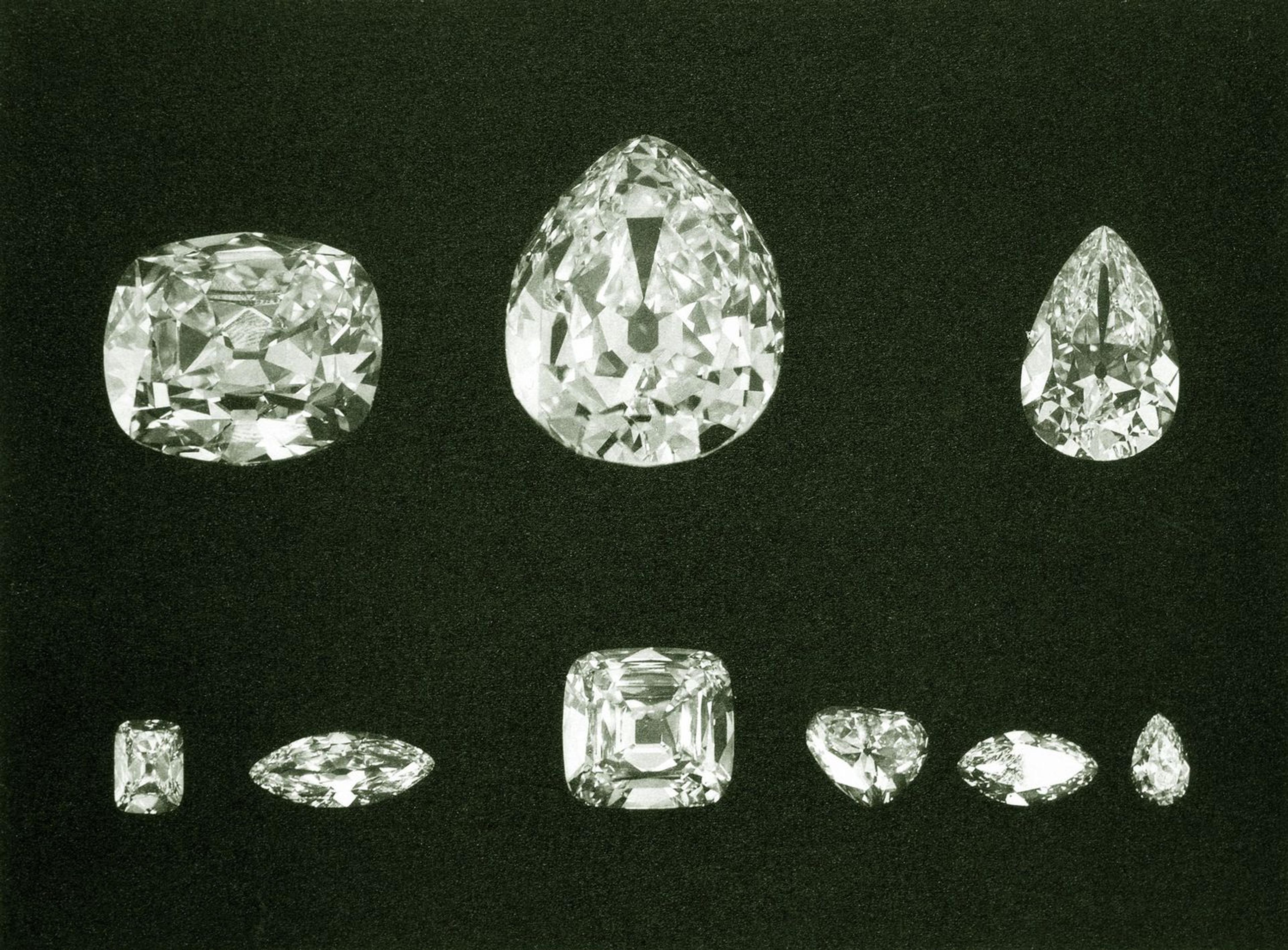

The 9 large diamonds cleaved from the Cullinan Diamond. The largest, Cullinan...

Ok, so now this giant rough diamond is in possession of King Edward VII. He then chooses Joseph Asscher & Co. of Amsterdam to cleave and then polish the rough stone. Joseph Asscher is the best cutter of this period. Ever heard of the Asscher cut? It’s basically a square emerald named for this guy. He’s the best, but even he needs to spend WEEKS studying the stone and planning how to cut it.

Based on the positioning of the stone’s inclusions, it’s decided to initially cut it into three parts. Asscher spent four days making an 1/2” deep hole incision at the hole’s weakest point in order to “cleave” the diamond. Cleaving is risky business. If the stone is hit incorrectly, it can shatter. The large rough Culliman was cleaved into nine major diamonds and 96 small brilliant diamonds. Once the stressful job of cleaving was done, Asscher & Co. spent eight months on additional cleaving, faceting (also called bruting) and finally polishing.

The Imperial State Crown made for the coronation of King George VI...

Queen Mary (Elizabeth II's grandmother) wearing the 1,005 carats of Cullinan diamonds....

And while the Cullinan’s size is remarkable, the process of cutting is the same for all stones. Today, diamond cutters utilize technology to know exactly where to cut to get the most brilliance from the stone. But even modern stones can take up to a full day to cut. And the antique stones? They are truly tiny works of art with every millimeter examined and touched by someone’s hand long ago.

Before we delve in, keep in mind that the history of diamond cutting, like much of jewelry history, is a little murky. As cutting technology developed, diamonds were often recut in the latest fashion. And sometimes newer diamonds were placed into older settings. All of that can make it challenging to date stones.

Roman diamond ring from the 3rd or 4th century. The natural uncut...

Rough octahedral diamonds in an 11th to 13th century ring from Pakistan...

For all their technological achievements, Romans weren’t able to figure out how to cut a diamond. And for them, that was part of its charm. The Romans loved diamonds for their hardness, not for their sparkle. The stone was believed to protect the wear from mishap and that protective power would diminish if the stone was in any state other than its natural one. So they polished the stone, so that the sharp angles were rounded off to create what is known as a cabochon. And it was set in its natural octahedral (or point-cut) form.

Ring with seven table-cut diamonds, 17th century. Benjamin Zucker Family Collection.

Elizabeth of Austria, Queen of France, wearing table-cut diamonds that are foiled...

Point Cut to Table Cut

With the fall of the Roman empire and the all-important Roman trade routes that had brought Indian diamonds to Europe, diamonds virtually disappeared from Western jewelry. Then in the 14th century, when Venetian merchants once again began trading with the East, diamonds began to trickle back into Europe.

The 40-45 carat point-cut diamond hanging from the bowknot was known as...

A large table-cut diamond worn on the third finger of the right...

The diamonds in Europe came from India. The best stones, the perfect octahedrons, were saved for the Indian market. The “reject” stones were exported to Europe. In an effort to improve the stones, cutters used diamond powder to polish off the top of the stones. In the process, they became aware of the impact that a table facet had on improving the stone’s ability to return light. Another way to improve a second-rate stone was to back it with foil or paint the back of the stone with a black substance (usually carbon black mixed with resin) before setting it. (This is why in old Renaissance portraits, the diamond is depicted as a black stone.)

Portrait of Mary of Burgundy, 1458-1482, sold at Sotheby's in 2018.

Ring of Mary of Burgundy, gold set with hog-back diamonds in the...

The table cut was made by simply polishing off the apex of the octahedron to create a single facet that looked like flat table.

It was around the mid-1600s that the hardness of the diamond came to represent constancy in love. As much as folks like to point the blame for diamond engagements on De Beers, the tradition started hundred of years ago.

So when Mary of Burgundy became engaged to Maximillian I of Austria in 1477, it made sense that he sent her a diamond ring as a sign of his sincerity. It was one of the first examples of a diamond engagement. The hog-back diamonds that made up Mary’s ring are elongated table cuts — a precursor to the modern baguette.

Rose cut diamond ring, sold at Christie Auction in 2018 for $4,375.

Wearing a diamond aigrette, choker and floral stomacher, Queen Charlotte, 1761. The...

Rose Cut

The rose cut is the first true instance of diamond cutting where the cuts are used to create facets. The way that the stone’s facets radiate from a small table — was thought to resemble a closed rose bud. The earliest rose cuts had only 6-facets, but by the 18th century, a rose cut diamond had 24 facets. For centuries, the diamond had beloved for its hardness. Suddenly, the stone was appreciated for its sparkle.

The 16th century invention of a spinning wheel known as a scaife made this possible. Diamond dust was spread on the wheel and the diamond was fixed onto an arm (known as the tang) that could be raised and lowered onto the rapidly spinning wheel. Until 1933, the diamond was soldered onto the arm with a mixture of tin and lead and had to be removed each time a new facet was started. Although the process is now mechanized, the basic tools: a diamond-dusted wheel and arm have not changed in hundreds of years.

In 1811, Napoleon presented his second wife, Empress Marie Louise, with a...

The main portion of the necklace is made from brilliant cut diamonds...

Brilliant Cut

Whereas the 17th century is thought to be the age of the pearl, the 18th century is the age of the diamond. Improvements in candles (less smoky and brighter burning thanks to whale oil) meant that grand events could take place at night. This led to a distinction between informal daytime jewelry and evening jewelry. Those evening parties triggered competitive dressing. Whereas for centuries, it was the stone’s hardness that was prized, suddenly consumers were all about the sparkle. Looking to capitalize on that twinkle, cutters begin to experiment with additional faceting.

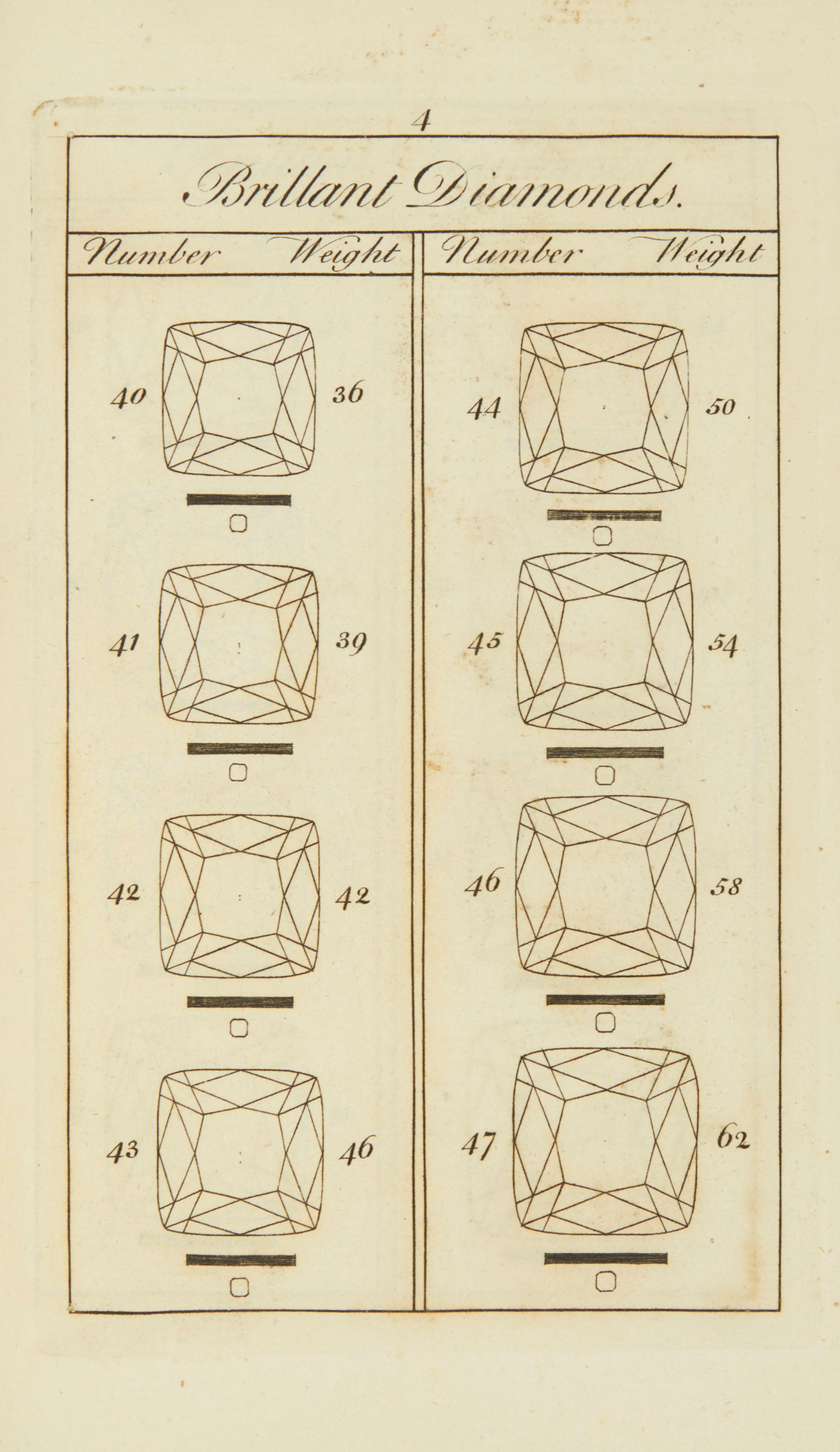

A page from David Jeffries's A Treatise on Diamonds and Pearls, 1751....

The 140-carat Regent Diamond, cut in England from 1704-1706 in the new...

In the lore of the brilliant cut, two names come up: A Italian cardinal in the French court, Jules Mazarin and another Italian named Vincenzo Peruzzi. The only reason we’re mentioning it is if you see either of those names: a Mazarin cut or a Peruzzi cut, just know that we're talking about brilliants.

The first brilliant cut diamonds (sometimes known as Mazarins) had 17 facets. They were soon followed by a 33-faceted brilliant known as the triple-cut or Peruzzi brilliants. When we think of diamonds today, it’s the sparkly brilliant cut diamond that we picture.

Unlike the flat-bottomed rose cut, the brilliant has a faceted lower element known as the pavilion which maximizes the ability of the diamond to refract light, and so ushered in open-back settings to highlight its “fire.”

Old Mine cut diamonds with enameled "coach covers," c. 1882-85. The Metropolitan...

The diamond stars in Empress Elisabeth's hair were made by the Austrian...

Old Mine Cut

For nearly two thousand years, the only known source for diamonds were the mines at Golconda in India. By 1725, the supply was nearly exhausted. Part of the appeal of a brilliant cut was that it could be used on older table or point cut diamonds that had missing corners. The cutters rounded off all the corners and created a cushion cut — which now know as Old Mine cuts because they were thought to come from the old mines in India. But as a new supply of diamonds from mines in Brazil hit the market in the 1730s, the newer stones were also cut into cushion shaped brilliants.

The large diamond is an 8.25ct European cut. The aigrette was made...

Old European Cut

A European cut stone is one that is almost perfectly round. In the late 19th century, a couple of technological innovations impacted diamond cuts. The first was a steam-driven bruting machine. Bruting is the process of creating a rough outline of the diamond after the cleaving but before the final faceting and polishing. One of the inventors, Henry D. Morse was also a diamond cutter and he used his invention to create round, symmetrical stones.

A second innovation, a power-driven circular saw made it possible to cut a round diamond, but retain the excess to be cut for smaller stones. Previously, the excess of a diamond was simply ground down into diamond dust.

These innovations coincided with the 1867 discovery of diamonds in South Africa. Suddenly, there were more diamonds available and the new perfectly rounded stone became a fast favorite.

The innovations in diamond cutting certainly didn't stop in the 19th century. Today diamond cutting is a technological endeavor where machines can calculate the best cut and create identical “products” on a mass-market scale. Because it’s so common to recut antique stones into more sparkly modern shapes, the artistry of cutters, who may have spent weeks or months working to bring out the best of an individual stone, is increasingly rare. All of which makes antique cut diamonds more precious.