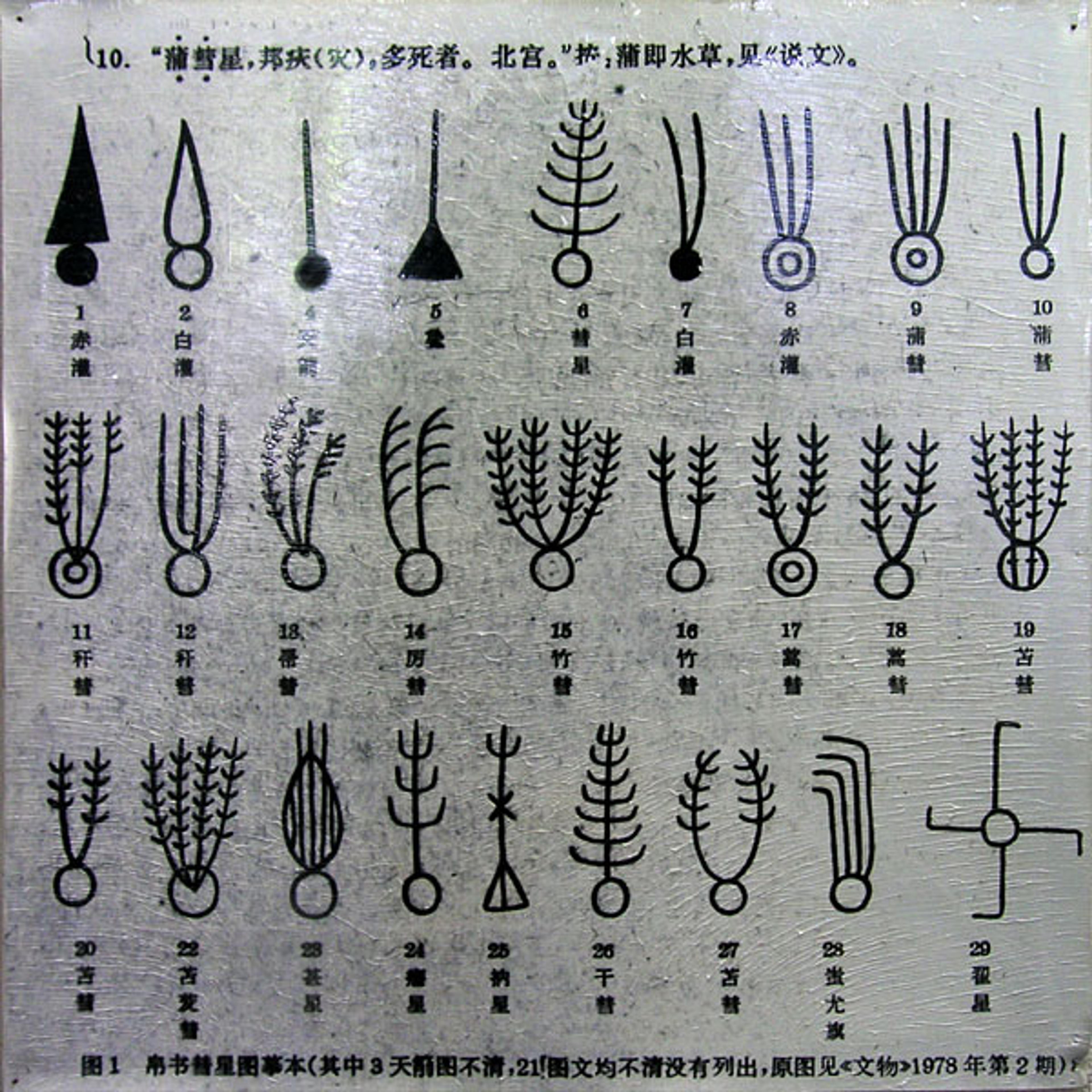

Long before telescopes, people were observing and theorizing about the bright figures streaking across the sky (actually, they're giant chunks of ice.) Chinese records of comets are the most extensive and accurate in existence, stretching back across three millennia.

This set of comet illustrations is from the western Han period in...

The Western world was a little late to the game, but we eventually got fantastical European depictions of Halley's Comet in paintings, woodcuts, and tapestries. The scariest (and mot famous, perhaps) is here, in the Bayeux tapestry from the 11th century. At the time, people considered the "long-haired star" a bad omen for the battle of Hastings — check out the crowd fearfully gazing at the sky.

Bayeux tapestry from the 11th century.

Halley's comet was pretty much universally seen as a sign of doom for the next few centuries. Its 1222 appearance is sometimes credited with inspiring Genghis Khan to dispatch his Mongols on an invasion of Europe, and its 1456 return famously overlapped with the Ottoman Empire's invasion of the Balkans.

Illustration of a comet from the Ausburg Book of Miraculous Signs, c....

Eventually, humans used science to determine that comets were not stars on fire, flaming arrows shot by angry deities, the Star of Bethlehem, discarded poop of the Gods, or parts of the Giant Ymir's skull (Norse myth).

Adoration of the Magi by Florentine painter Giotto di Bondone (1267-1337). Giotto...

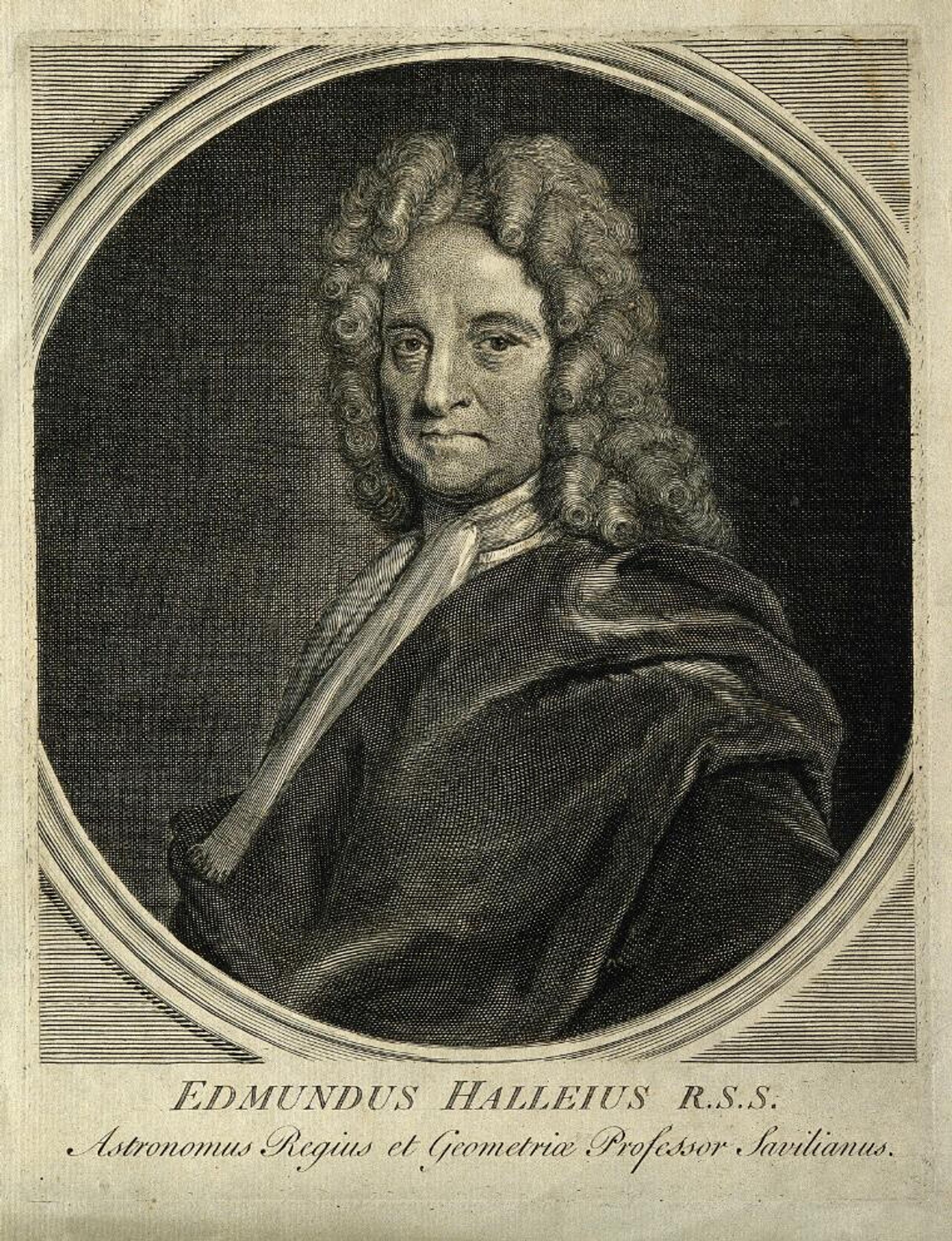

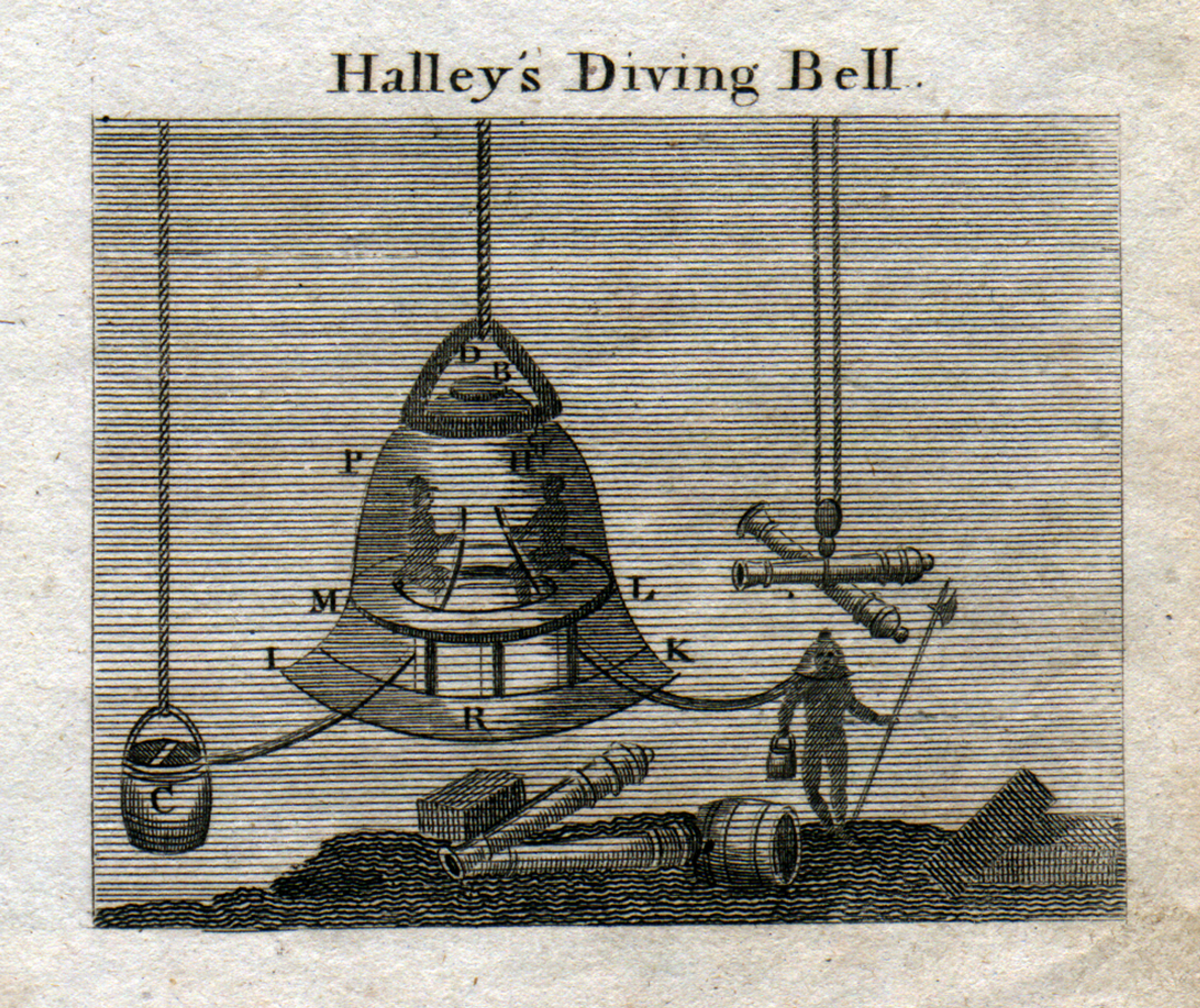

In 1682, the English royal astronomer Edmund Halley started researching the periodic comet that he observed in the sky. During the busy next few years, he helped Isaac Newton work on the Laws of Motion, learned Arabic, invented the diving bell, and tested it personally in the River Thames (suffering one of the first recorded cases of middle ear barotrauma from the pressure). Halley did an astonishing amount of work to advance the science on star maps, terrestrial magnetism, and calculating the size of the solar system. He also became the second Astronomer Royal in England. The first, Rev. John Flamsteed, observed snootily that Halley ''... talks, swears and drinks brandy like a sea captain.''

Edmund Halley. Line engraving after R. Phillips. Credit: Wellcome Collection.

Halley and five companions dived to 60 feet in the River Thames,...

halley also got a few things wrong: he hypothesized that the earth is hollow, with creatures inhabiting the space inside. Also, he thought that maybe the biblical story of Noah's flood could have been an account of a comet's impact - an interesting idea that has been rejected by geologists. What he got right? In 1705, he hypothesized the comet sightings of 1456, 1531, 1607, and 1682 were of the same comet. Halley had figured out that bodies circle the earth in an elliptical orbit, and predicted the comet would return in 1758. He didn't live to see this second return, but his name became attached to the celestial body forevermore.

A depiction of Halley’s comet in 1759 from a 1910 issue of...

Halley's comet, photographed in 1986.

When Halley's comet was about to re-appear in 1835, people got really excited. It was time to commemorate the comet in jewelry form. Telescopes existed, but they were pretty rudimentary. Jeweler's imaginations provided much more exciting designs.

These brooches come from that 1835 Halley’s comet appearance. They’re decorated with sparkly gems, swirling ornament and all the fantastic details you want from Georgian-era jewelry.