This glittering jewelry innovation originated in the 1700s. To make cut steel, melted horseshoe nails were formed into tiny faceted beads. Those small steel gemstone-like studs were then riveted one-by-one onto a base plate. It was an English invention that quickly travelled throughout the world.

Example of 18th century cut-steel earrings. This painting was acquired by the...

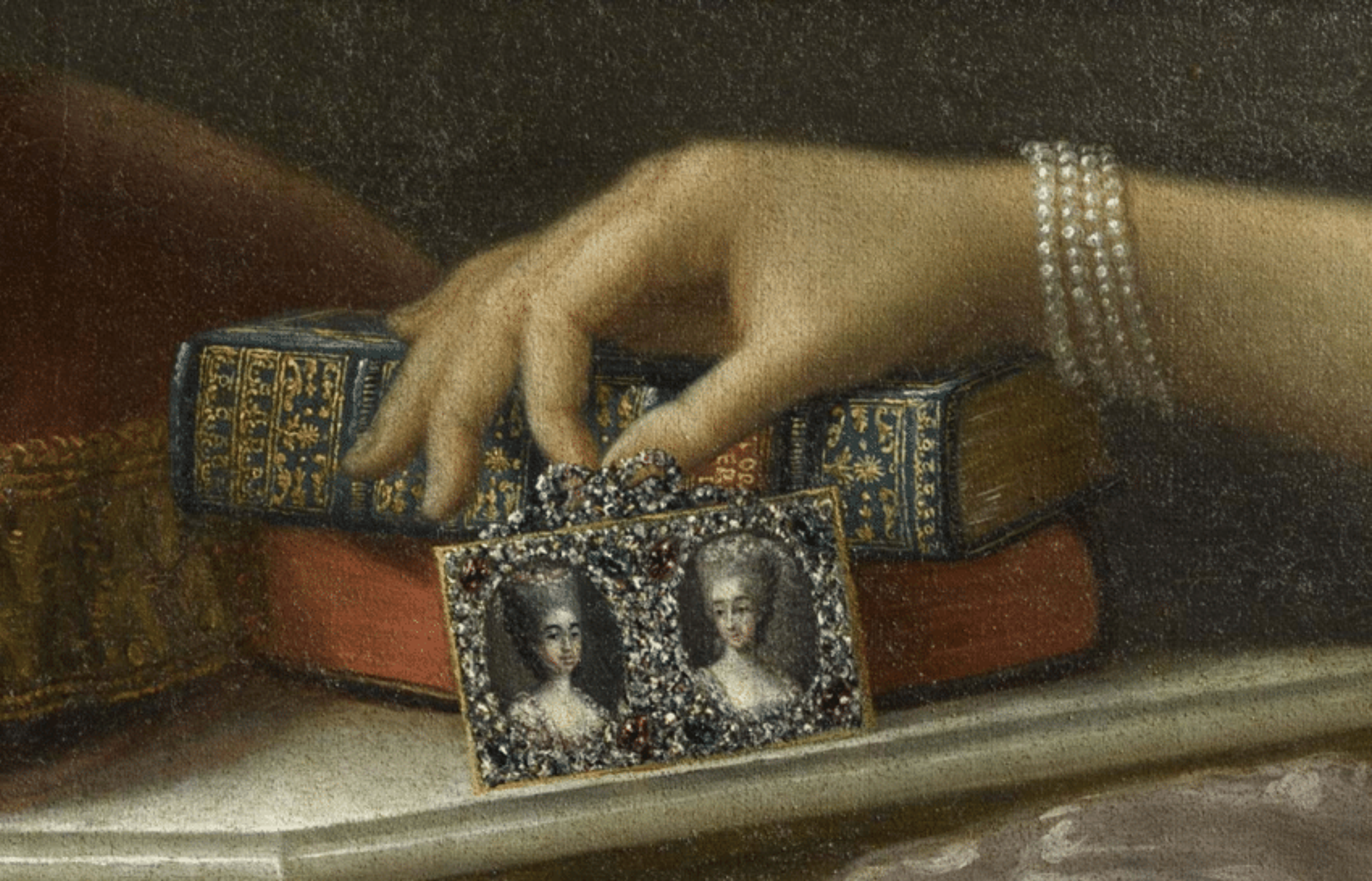

What looks to be a cut steel picture frame in a detail...

The 18th century is known as the Age of the Diamond. Technological advancements in diamond cutting meant that jewelry suddenly was able to sparkle in a way that it never had before. The timing for this sparkly diamond was fortuitous. Improvements in candles (less smoky and brighter) meant that grand events could take place at night. And everyone wanted to shine (cue Rihanna).

Cut steel could — quite spectacularly — imitate the glimmer of diamonds at a fraction of the cost.

Because of the complexities in manufacturing (and the workmanship that was required) it grew beyond a simple imitation to an art in its own right.

Cut steel was the perfect compliment to exaggerated men's fashions in the...

Cut steel button, 1850. Victoria & Albert Museum.

Part of what made cut steel possible was Industrial Age cheap labor (we're in pre-labor law territory). But this wasn't some assembly line product; every piece of cut steel manufactured took careful craftsmanship. The studs were made from decarbonated cast steel, which was case-hardened (a process where the outer "case" is hardened but the inside is soft), then the studs were faceted by cutting against a pewter wheel. Next were then polished with first fine emery and a hard brush, and then by hand with a special putty. Finally they were riveted onto pierced base plates which had to be drilled and cut by hand, too.

Louis XIV of France, 1701 by Hyacinthe Rigaud, Versailles.

Not only did his shoes have diamond buckles, but they were thought...

The first cut steel pieces were made to adorn shoe buckles in the early 18th century. Because style trends are ever-changing and not always sensible, shoelaces had been suddenly deemed unfashionable. By the mid-1737, buckles were a common dress-code requirement. Your ticket to the theater was likely to read: "Gentleman cannot be admitted wearing shoe strings."

An example of the downside of paste or diamond! A stone can...

Cut steel shoe buckles with gold edging, English, 1780s. The Los...

The center of cut steel production was Birmingham, England. And there, one manufacturer stood out from all the rest: Matthew Boulton. He had been born in 1728 into the industry — his father manufactured small metal products. But the younger Boulton had a special talent for marrying the latest technology with the latest fashion. He also was continually expanding — he even founded a mint. He schmoozed with dignitaries and advocated for his steel products. Fortuitously, he became quite close with the Russian ambassador to Catherine the Great. When the ambassador toured the mint, Boulton made sure to send the Empress some his cut-steel necklaces.

Russian Empress Catherine the Great adored cut steel jewelry. Her pieces were...

The huge fashion for buckles created a giant English industry set up to feed the demand in both England and France. (Boulton exported countless buckles and buttons to France, where they were often re-purchased by the English, thinking they were French-made.) In 1759, Louis XV encouraged the nobility to donate their gold and gemstone jewelry to help fund the Seven Years War (when France and England fought over colonies and involved almost all other European powers). Either you complied with the law and gave up your family jewels to be melted down for the war chest, or you quietly hid your jewelry until the war was over. But you certainly weren't seen wearing your fanciest ornaments — that would be unpatriotic. Cut steel jewelry, made of non-precious metal, was perfectly positioned to fill that bling gap.

Queen Charlotte, 1761-69 by Allan Ramsay. Royal Collection Trust.

A satirical cartoon depicting a fashionable couple meeting in the park. The...

However as France marched toward its Revolution, steel trade across the Channel virtually halted. Queen Charlotte helped somewhat to revive the fashion for steel cut jewelry by wearing buckles and buttons. But if the slow-down with France was bad enough, buckles began to be considered uncool. So in 1791, English buckle makers (including Matthew Boulton) obtained an audience with the Prince of Wales. In attempt to help the industry, the Prince ordered the wearing of buckles at his court.

The boost didn't last long, but it helped the art form evolve. As buckles disappeared, manufacturers pivoted by creating more intricate cut steel jewelry. And the jewels got bigger and more elaborate.

This tiara is belived to have been made for Joséphine’s daughter, Hortense...

Georgian cut steel tiara, Erica Weiner Archives.

Napoleon was even a fan of the style, which certainly played a part in the longevity and popularity of cut steel. In 1810, he gifted a cut steel parure to his second wife, Marie Louise, upon their marriage. (In reality, he couldn't afford a gemstone parure!). Cut steel jewelry became the staple of any fashionable lady's evening wear ensemble. These dark, glimmering pieces give off a diamond-like shine that was (still is!) particularly effective in low lighting, which at the time was candlelight.

These were nighttime jewels, and they were bewitching.

The style was so in demand that at the peak of the trend, a fine piece of cut steel jewelry could command a higher price than gold. Silver jewelry was even made to resemble cut steel. The imitation became imitated — a sure sign of iconic status.

Developments in technology toward the mid to late 19th century made it possible to produce these glittering steel elements by machine, making them more affordable and accessible — but by the early 20th century people had moved on to other jewelry trends. A look at the construction of the rivets, facets and baseplate will tell you if your cut steel piece was made in the early days of the trend, when everything was constructed painstakingly by hand, or later on using machine-made shortcuts.