Why does monogrammed jewelry have such a hold on us? Maybe Dale Carnegie has the answer. In his perennial best seller, How to Win Friends and Influence People (1936), he wrote “Remember that a person’s name is to that person the sweetest and most important sound in any language.”

This 4th century ring bears the chi-rho monogram to indicate that its...

Cross monogram ring spelling "IOANIS" or John, made in the 6th-7th century....

Before we delve into the history, how about a little etymology for your next crossword clue? The word monogram combines the Greek work monos (one, sole) with gamma (letter). A true monogram is not just initials but is a singular design. A design composed only of initials is properly known as a cypher.

Keep that little piece of trivia in your hat, we’re going to look at both cyphers and monograms (and even initial jewelry and nameplates).

History shows Dale Carnegie was right: we all love the letters of our names.

Two sides of a coin: on the left is the monogram of...

Considering we have the Greeks to thank for the word, you might guess where we’re headed next. The earliest monograms hail from Ancient Greece where they served as royal signatures for coins. The monograms served as proof of authentication and identified where the money was made.

It wasn’t until the 8th century that monograms became anything more than a way to mark money. What changed? A medieval emperor named Charlemagne who was driven to unite all of Europe under his rule. He knew that no matter local language, everyone could understand the symbolism of his monogram. And so the trail of Charlemagne’s monogram marked his conquests throughout Europe.

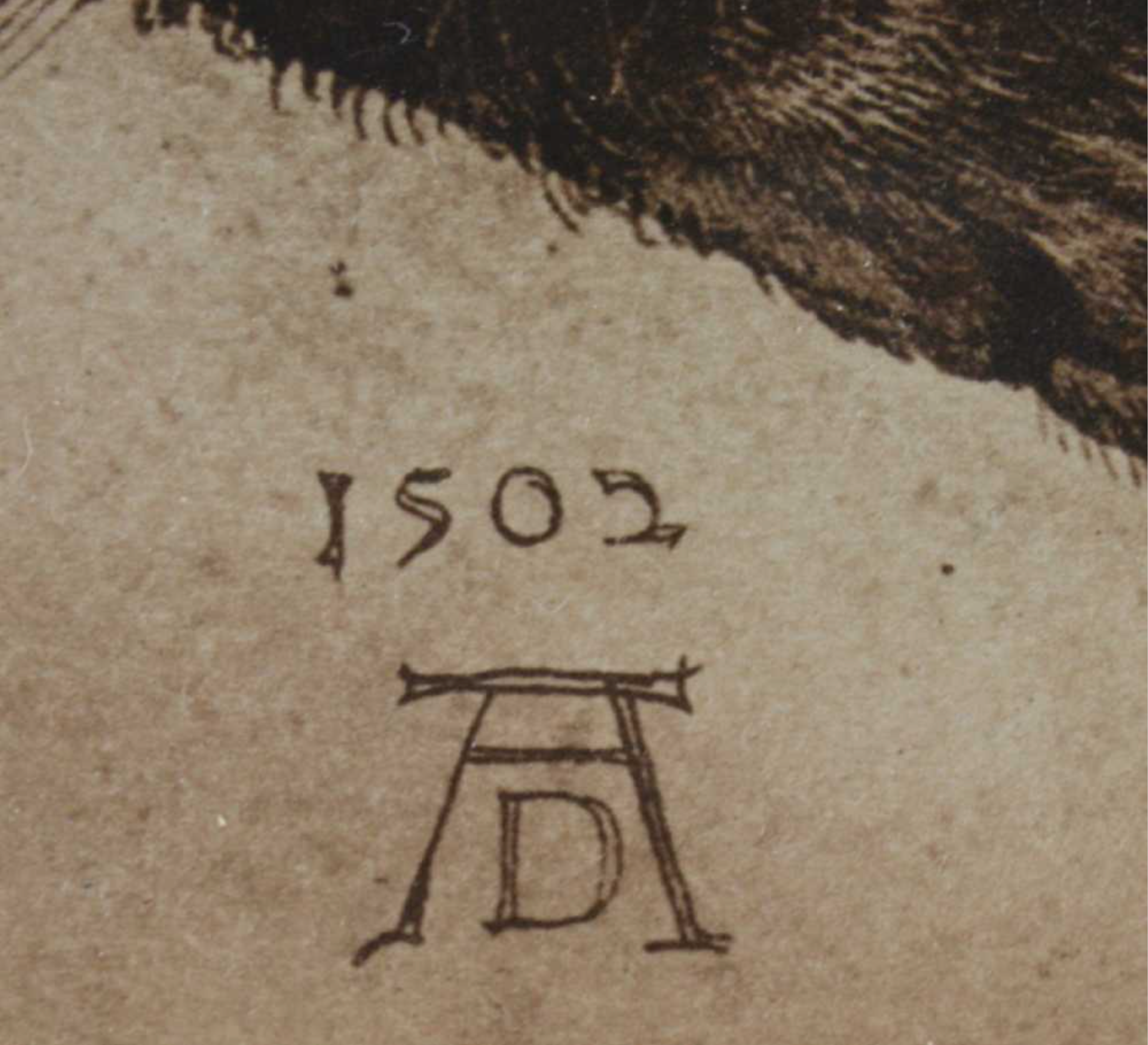

Possibly the most famous craftsman monogram is this by printer maker Albrecht...

In symbolically ricH medieval Europe, the monogram became the practical stamp of ownership. During this time, there was an increase of guilds (associations to regulate a particular trade). There were strict laws and fines issued, if those rules were broken. Monograms became a critical way for craftspeople to identify their work and their participation in a guild. But even peasants might have had a monogram. Their reason was practical. Since laundry day was a village-wide event with everyone throwing their clothing in big vats, they used an embroidered monogram to mark what belonged to whom.

Anne Boleyn, second wife of King Henry VIII wearing her initial necklace,...

Artist Hans Holbein also designed a pendant for Anne with an intertwined...

Monogram jewelry played an important role in 15th and 16th England. This was the time of the Tudors (Henry VIII) and Elizabethan (Elizabeth I) who were guided by a belief that God had chosen them. Part of the duty of their rank was to dress in a way that conveyed their part of the “Great Chain of Being.” Dressing grandly was serious business: Jane Seymour (Henry VIII’s third wife) once rejected a potential lady-in-waiting because the pearls on her girdle weren’t large enough.

Note the ‘H’ on the chain. Detail from Henry VIII by Hans...

Queen Elizabeth I as a teenager wearing what is believed to be...

The Tudors loved their initial jewelry. It checked two boxes: not only was it luxurious, but it also marked the wearer as a chosen individual. One of the most iconic initial jewelry pieces from that period is the ‘B’ necklace worn by Anne Boleyn. Details surrounding the piece (and the pendant itself) have been lost to history, but it’s supposed that her father, Thomas Boleyn, had given it to her. (That replicas of the necklace are one of the best selling items in U.K. museum shops says something about the enduring power of the design.)

Not one to be outdone, the heavily bejeweled Henry VIII was said to own a similar brooch with his initials. (His was the court where it was fashionable to have gold ear picks and gold toothpicks.)

Anne, mistress of Francis I, wearing an initial ‘A’ pendant with a...

The ‘K’ on the necklace possibly stand for “Katherine” of Aragon (first...

Remember the definition of monogram as a design and cypher as a single letter? Beginning in the Tudor period (1485-1603), each monarch created a royal cypher as a way of symbolically asserting their power. You can recognize a royal cypher by the not-so-subtle crown hovering over the initials. The Russian monarchs were particularly adept at crafting over-the-top ciphers. (Hungry for more? Scroll through the British royal family ciphers.)

This is the cypher for Empress Maria Fedorovna (Empress of Russia from...

This cipher pin consists of the Russian letters of the last two...

Monograms and cyphers remained mostly a royal or governmental thing until economic growth during the 18th and 19th centuries meant a new influx of people had both the means and social aspirations to adorn personal and household possession with monograms. Believing that a monogram was the ultimate sign of prestige, upper class Victorian families monogramed nearly everything.

In Appletons’ Journal, a 19th century popular magazine, writer A. Steel Penn fretted, “From seals and rings, jewelry and watches, cards and note-paper..., they have descended to... dog cloths and shirt collars, until there seems to be no spot left on which to apply them, unless it be to tattoo them on the forehead.”

Maria Teresa de Silva wearing a monogram ‘M’ bracelet on her wrist....

Brooch monogrammed with ‘A’ and ‘L.’ It has a compartment on the...

1970s deadstock nameplate bracelets, EW archive.

A new kind of personalized jewelry entered the scene in the second half of the twentieth century: the nameplate. It began as a New York jewelry phenomenon in the 1970s (or even earlier). The jewelry was a way for those in Black and Latinx communities to display their non-Anglican names with pride.

The trend crossed into the mainstream when, in the late 1990s, costume designer, Patrica Fields, spotted neighbors kids wearing them and a decided that the main character of Sex and the City needed one. And the necklace became synonymous with the show. Frustrated with the jewelry’s label as “the Carrie necklace.” Isabel Flower, Marcel Rosa-Salas and Kyle Richardson created a multi-pronged approach to right the narrative. The center of their effort is a Instagram account called Documenting the Nameplate. (Their book is due out in 2022.)

Monogram, cypher, initial or nameplate? The personalization world is your oyster. But for us history lovers, there’s no better way to chart an object’s provenance. Recently a monogram on a rock crystal heart, led us down a research rabbit hole where we found Fairbairn’s Book of Crests. In it, we learned that the Farrier family crest is a winged horseshoe (fun fact: a farrier is a craftsman who shoes horses) and not only that, there was a son born to the Farrier family in 1847 whose name was George Henry. Our locket may not have been made for that George, but it illustrates why we adore finding monograms.