As we dive in to the traditions and history of amulets, we will focus on symbolic elements like horseshoes and crosses. We are saving the talismanic properties of precious stones for another time.

The scorpion jewel worn on Elisabetta's forehead is thought to be related...

Give me an amulet that keeps intelligence with you, red when you love, and rosier red, and when you love not, pale and blue.

— Ralph Waldo Emerson, 1842

An amulet, talisman or charm is a personal ornament, which because of something inherent in the object (it's shape, material or color), is believed to endow its wearer with special powers or capabilities. The word is derived from the Latin term amoletum: a means of defense.

Every culture has an amulet tradition. It is part of our humanity.

Magical thinking around jewelry is part of its history (and a big reason why we love it). We've covered topics surrounding the protective power of hearts, birds, snakes, aromatic jewelry and coral in the past.

In the Ancient World, there was a belief in a malignant force called the evil eye, which is brought about by a malevolent glare - usually when the recipient is unaware. (Historians think the concept dates back 5,000 years). The evil eye was the harbinger of ill health and poor fortune. It's hard to overstate how worrisome it was for our ancestors. Amulets offered the only known protection.

Belief in the evil eye is alive and well today. If you've ever "knocked on wood," you've tried to combat the evil eye (see our last amulet for more). Erica's Jewish grandmother — along with generations of Jewish people before her — uttered the word "Kinehora" to immediately ward off the evil eye. It's a contraction of three Yiddish words: kayn ayin hara, literally “not (kayn) the evil (hara) eye (ayin).”

Here are ten powerful amulets and how they came to be.

The Phallus

Gold Romano-British pendant in the shape of a phallus. Lynn Museum, Norfolk...

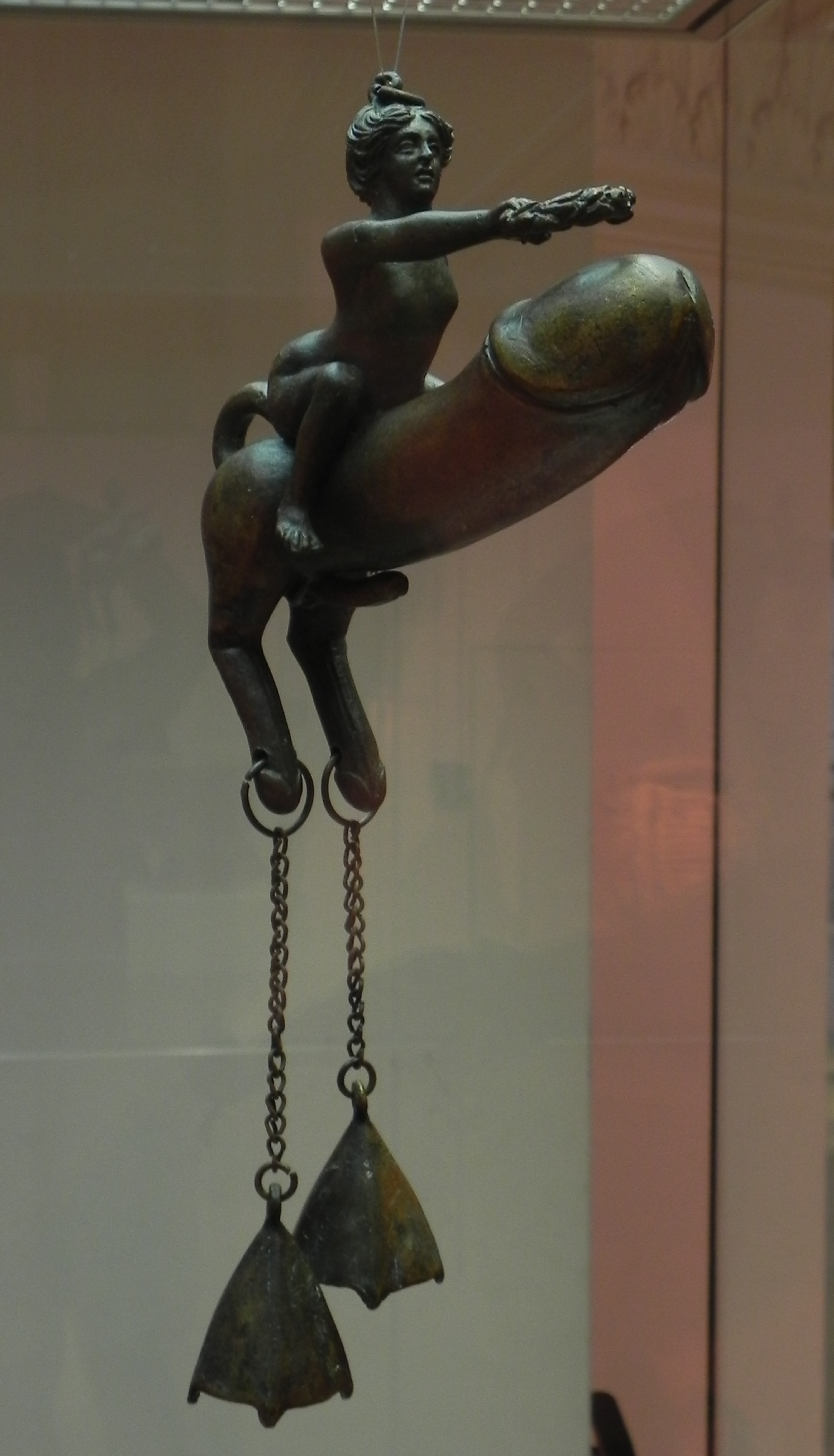

Roman tintinnabulum, 1st century AD. Museu d'Arqueologia de Catalunya. Barcelona. Photographed by...

So, if you saw someone wearing the charm above as a necklace, what would your reaction be? Would you laugh? Would you feel embarrassed? Aha! You've just uncovered the reason that Romans believed the phallus would protect against evil. Whatever emotion seeing an erect phallus brings up was thought to distract and divert attention from evil at work. The phallic deity was called Fascinus, from fascinare, meaning "to cast a spell." It's also the root of the English word fascinate.

Sometimes the phallus was depicted as urinating or ejaculating — so as to literally blind the Evil Eye. Remember my Jewish grandmother? Sometimes she would also superstitiously fake-spit three times — ptoo ptoo ptoo — which likely relates back to this ejaculating, blinding, anti-evil eye concept. Liquids, whether wine, semen, saliva or water has always had extra-strong folk magic power against the malicious glare.

There was emotional power in the phallus, but there was also belief in its physical power. In Ancient Greece and Rome, the schlong was equated with a weapon in collective imagery. In popular stories, the hero might punish the wicked by explicitly using his erect phallus instead of a club.

Ancient Rome was a world in which one in four babies died in infancy, and then fifty percent of those who survived infancy died before the age of eighteen. In the absence of modern medicine and surgery, phallus amulets were often employed by hopeful parents to protect their male children. A weiner hanging on a kid's neck is cute, but a dick could also be hung outside of homes and businesses. There was even a special winged phallus, a tintinnabulum, that was a kind of wind charm/door bell. The ancient Romans didn't, but I'll go ahead and call it a ding dong. (Fun fact: Sigmund Freud was an avid collector of ancient phallus amulets: part of his penis envy theory.)

The Scarab

In Ancient Egypt, nearly all jewelry had some magical significance. Sometimes it was the material that might protect the wearer, like shells from the Red Sea. Or it might be the form: a falcon or bull could grant the powers of those animals. A fish, obviously a great swimmer, was worn to prevent drowning. A frog was worn to insure fertility (because so many of them appeared annually when the Nile flooded) One hugely popular amulet was the scarab beetle, symbol of the Sun God Ra. Because it lives off decaying material, it symbolized rebirth. It was known to protect the living from illness and ensure eternal life for the dead.

An Egyptian funerary mask with a blue glass scarab - a symbol...

Heart Scarab of Hatnefer, 1492-1473 B.C., The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Bulla

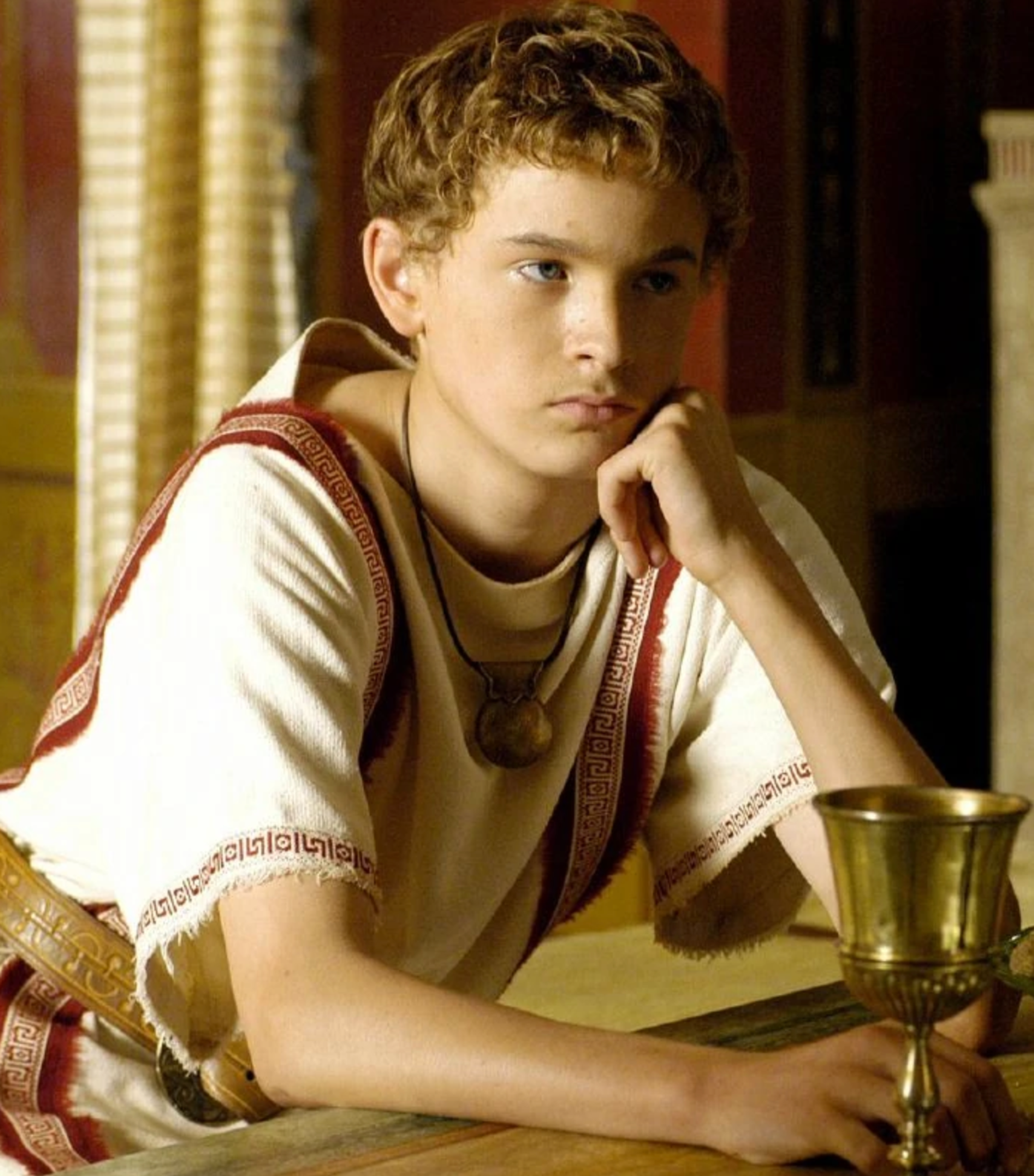

For Etruscan and Roman boys, the most visible amulet would have been the bulla. It was given when the baby reached nine days old and was worn around the neck. A boy would wear his bulla until his received his toga virilis and became a man (sometime between ages of 14 to 17 years — his father would decide when he was ready. (The jury is still out on whether girls also wore bullea.) The bulla was hollow and could be filled with perfume or a charm. Essentially, they were an early form of lockets. (For all the reasons above, the majority of bullea held a tiny penis.)

A young Gaius Octavian Caesar wearing a toga praetexta (the toga of...

Wearing an ancient bulla, Princesse de Broglie, 1851-53 by Jean Auguste Dominique...

The bulla had a later resurgence that coincided with continued excavations at Pompeii and Herculaneum throughout the 18th and 19th centuries. Every new jewelry find was cause for excitement. Many designs (including bullae) were replicated, but some women (like the stylish Princesse de Broglie, above) preferred the real thing and wore actual artifacts.

Lunula

A gold lunula dating from the Early Bronze Age, British Museum.

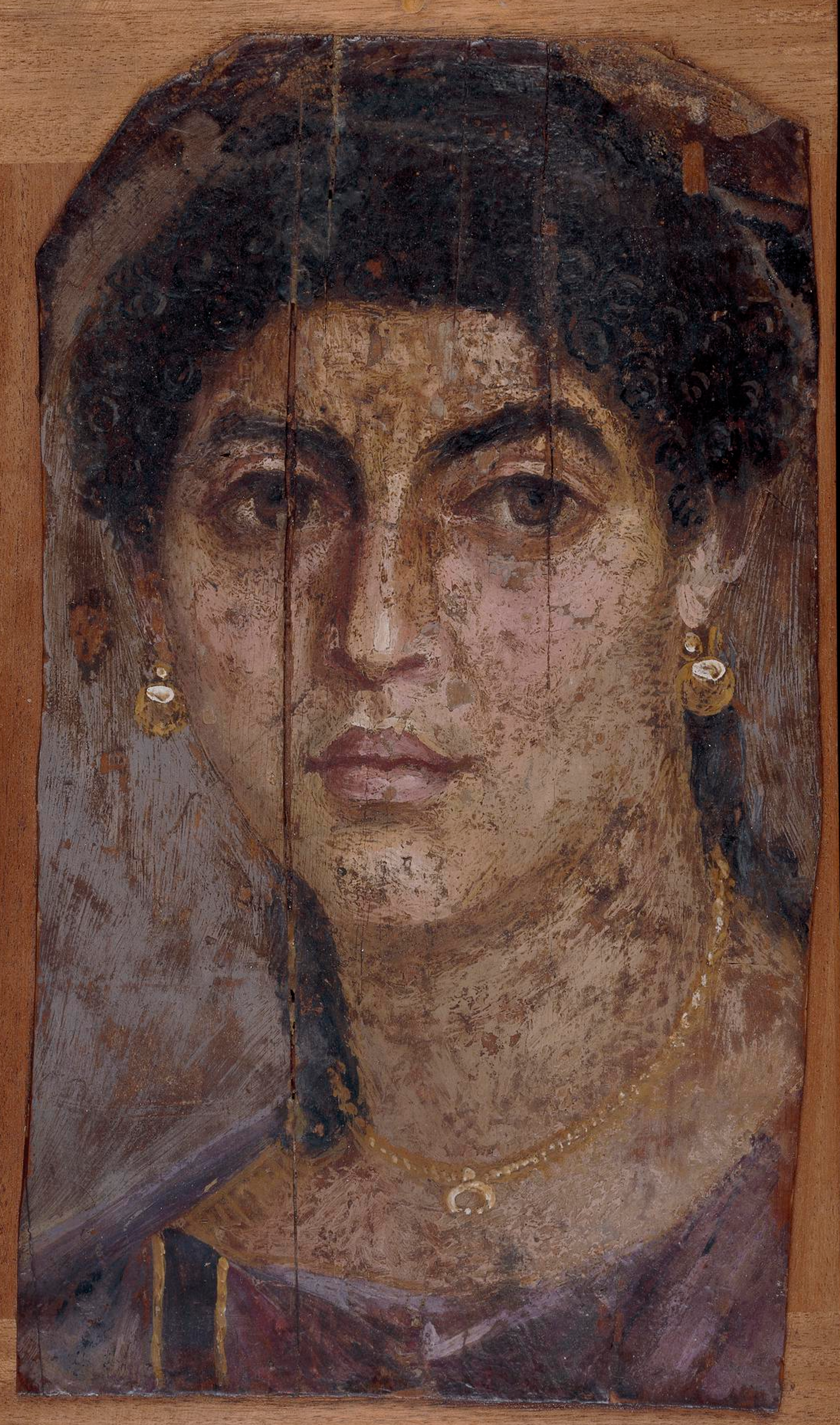

A mummy portrait from Roman-Egypt depicting a woman wearing a lunula pendant,...

While young boys were protected by the fascinum, the divine phallus, young girls had the power of the moon behind them. Worn by children, women and even animals, the lunula was an amulet in the shape of a crescent moon. The shape placed women and children under the protective powers of Greek goddesses Artemis, goddess of hunting and nature who used the moon to her advantage and Selene, goddess of the moon. The moon also evoked the menstrual cycle so the amulet would have protected women's health and fertility.

The lunula was one of the Roman amulets that the early Christian Church found challenging to prevent people from wearing. In the fourth century, Gregory of Nazianzus wrote in On Baptism, "You have no need of amulets... with which the Evil One makes his way into the minds of simpler folks, stealing for himself the honor that belongs to God." He then laments the way that "foolish old women" tie moon-shaped plates of gold, silver or cheaper material onto babies."

Horseshoe

Sometime between the 1st and 3rd centuries, the Romans began worshipping Epona, protector of horses and patroness of the Roman calvary. She was the only Celtic divinity ever worshiped in Rome. It is likely around that period that ancient Romans adopted the Celtic practice of protecting hooves with nailed-on shoes.

"Saint Dunstan and the Devil", illumination from the "Luttrell Psalter", ms. Add...

Horseshoes were all the rage in late Victorian England. But they were...

The beginnings of the horseshoe as an amulet is tied to the patron saint of goldsmiths and jewelers. According to lore, in the 10th century a man named Dunstan was working in England as a farrier when the devil entered the forge and demanded his horse be reshod. Dunstan caused the devil great pain by either nailing iron shoes on him or by twisting his nose with hot tongs (the method of torture sometimes changes). He made the devil promise to give the horseshoe a wide berth and never enter a home where one is hung.

Part of the luck of the horseshoe is its seven nails. Humans have considered the number seven to be lucky for thousands of years. Many different ancient cultures believed that the seventh son would be gifted with magical powers (both good and evil). Since God was said to have made the world in six days and rested on the seventh, the number seven appears throughout the Bible to indicate completeness. In Islam, Judaism and some ancient Mesopotamian religions, there are seven heavens. In Confucianism, yin, yang and the five elements represent harmony (that's seven, if you're counting). There are seven higher worlds and seven underworlds in Hinduism. In Buddhism, the newborn Buddha takes seven steps. Even the religious agnostic aren't left out: there are seven colors in the rainbow. So seven nails on a horseshoe is just one of the many magical sevens out there.

The Hand: Mano a Mano

In Ancient Rome, there were two hand gestures replicated (usually in coral) in miniature and worn as an amulet to protect against the Evil Eye.

Portrait of the Infant Maria Anna, by Juan Pantoja de la Cruz...

Pendant: coral hand with setting and ring, Louvre Museum.

A mano figa is a hand where the thumb protrudes between the pointer and middle finger. In Etruria, ancient Italy, the sign was an obscene one. Figa, or fig, was a slang term for female genitalia, and the hand sign was a reference to heterosexual sex. The amulet was worn as protective measure against the Evil Eye (the obscenity of the figa providing a similar distraction as the phallus), but it also was worn as a symbol of fertility.

A mano cornuta is a hand making the "sign of the horns." Some historians theorized that the sign is a reference to the neopaganism worship of a fertility goddess whose husband was the Horned God. Others think that the sacredness of the head of a horned animal (likely a bull) derives from its resemblance to the female genitals.

If you look closely, you can see the woman making the...

Heh heh. This rules.

Even its use at heavy metal concerts can be traced back to the Mediterranean where it was used to ward off the Evil Eye. According to rock lore, Ronnie James Dio of Black Sabbath is credited with popularizing the sign. He said he learned it from his Italian grandmother. To protect against ill fortune, one should point the "horns" downward or in a leveled position — it becomes an offensive gesture (implying cuckoldry) if pointed directly at someone.

Teeth

Roman teething charm set in bronze handle. To get its full amuletic...

Late 19th or early 20th c Charivari charm: marten (wild weasel) jaws...

Babies cry a lot when they're teething. The ancient Roman remedy was the wearing of teeth, which would — according to the laws of sympathetic magic, which uses a related object — ease painful symptoms. The best teeth were those from strong animals like a wolf, dog or horse. (Strong teeth beget strong teeth.) An adult toothache could also benefit from the soothing power of wearing a tooth as a charm. The demand for animal teeth was so great that artificial teeth were sometimes created using bones.

Fast forward to the 18th century and onward. Bavarian men wear animal teeth (and sometimes fur, bones, claws, antlers or quills) on their lederhosen as amulets to ensure a successful hunt. Set in silver, these trophies were passed down for generations within families and were not available for purchase. Much like sympathetic magic, the charms gave the wearer the attributes of the animal whose teeth and other parts adorn the Charivari. Most dynamic: the hinged jaws of a wild weasel, which could open and close in a tiny, fierce snarl.

Eyes

String of 5 Eyed Beads from 12th century Egypt, The Metropolitan Museum...

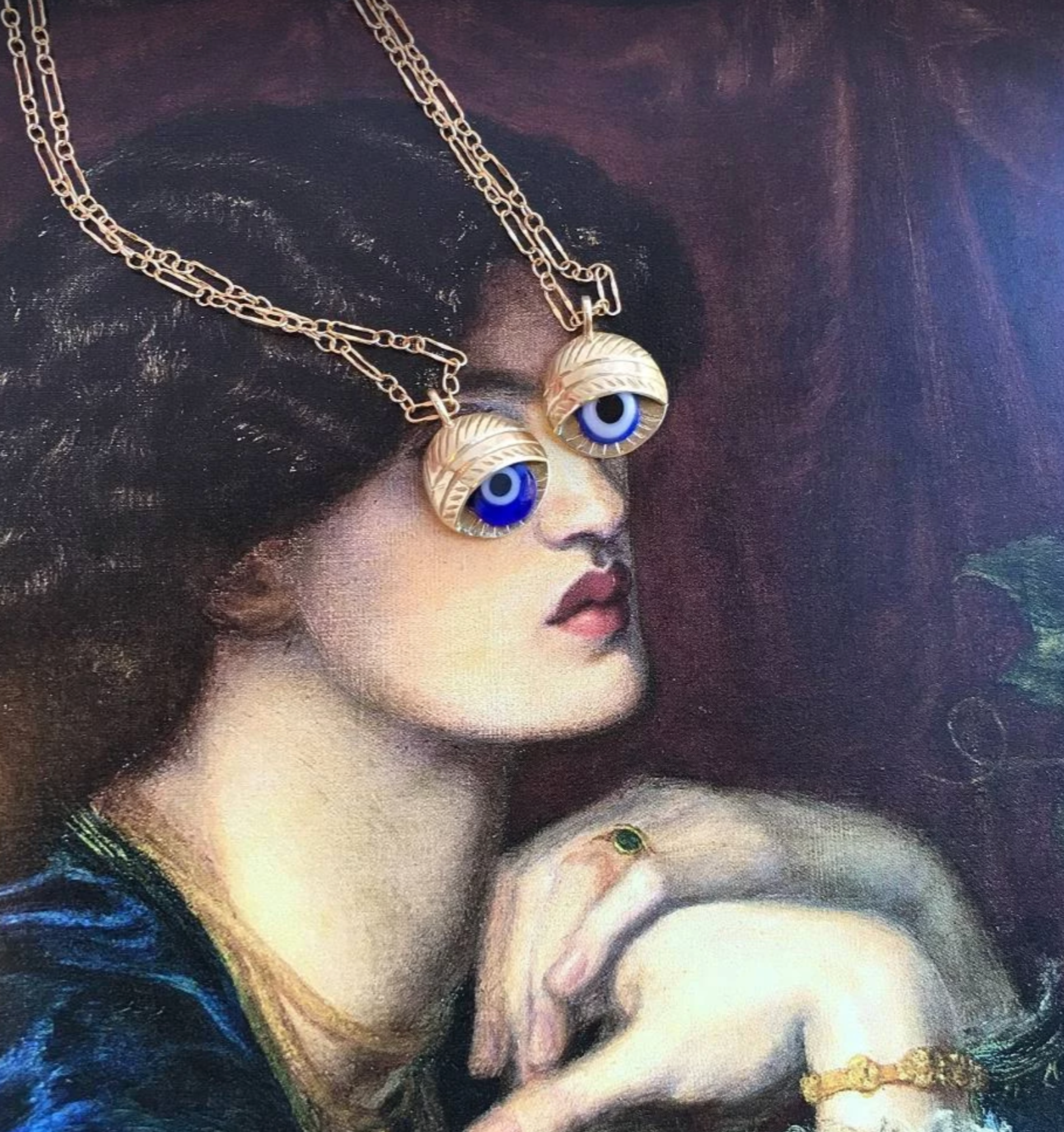

Evil Eye necklace. Erica Weiner Archive.

A powerful talisman against the Evil Eye is another eye. In the Arab world a blue glass eye-like charm is known as a nazar, or sight in Arabic. It is literally an "eye for an eye." Do you remember the school yard taunt "I'm rubber, you're glue. Whatever you say bounces off me and sticks to you"? That's the power of a nazar. Whatever maliciousness intended for the wearer will reverse course and stick to the evil deliverer who will be in trouble the next day unless a protective phase like "With the will of God" is recited. Glass beads were introduced in the Mediterranean in about 1500 B.C., and evil-eye beads were manufactured almost as soon as glass technology made it possible.

Cross

Used as a hieroglyph to write the words "live", "alive" or "life"....

Cross pendant, 5th-8th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The first cross was the ankh, an ancient Egyptian hieroglyph used to write "live," alive," or "life." It was the Coptic Christians of Egypt in the 4th century who adopted it as a symbol of Christ's promise of everlasting life. (Early Christians in Rome adopted the fertility symbol of the fish as a sign of their faith.) Christian churches did not encourage the use of the cross as an amulet, but as a marker of faith.

In 1683, church provost Christian Blichfeld started shifting some graves around in St. Bendt's Church to make room for a tomb for his wife. (Strange, right?) In the process, he removed two royal tombs and discovered a Byzantine reliquary cross that was thought to belong to Queen Dagmar, who had died in 1212. The cross became known as the Dagmar Cross. It became such a national symbol that replicas are still given to Danish girls in connection with their baptism or confirmation.

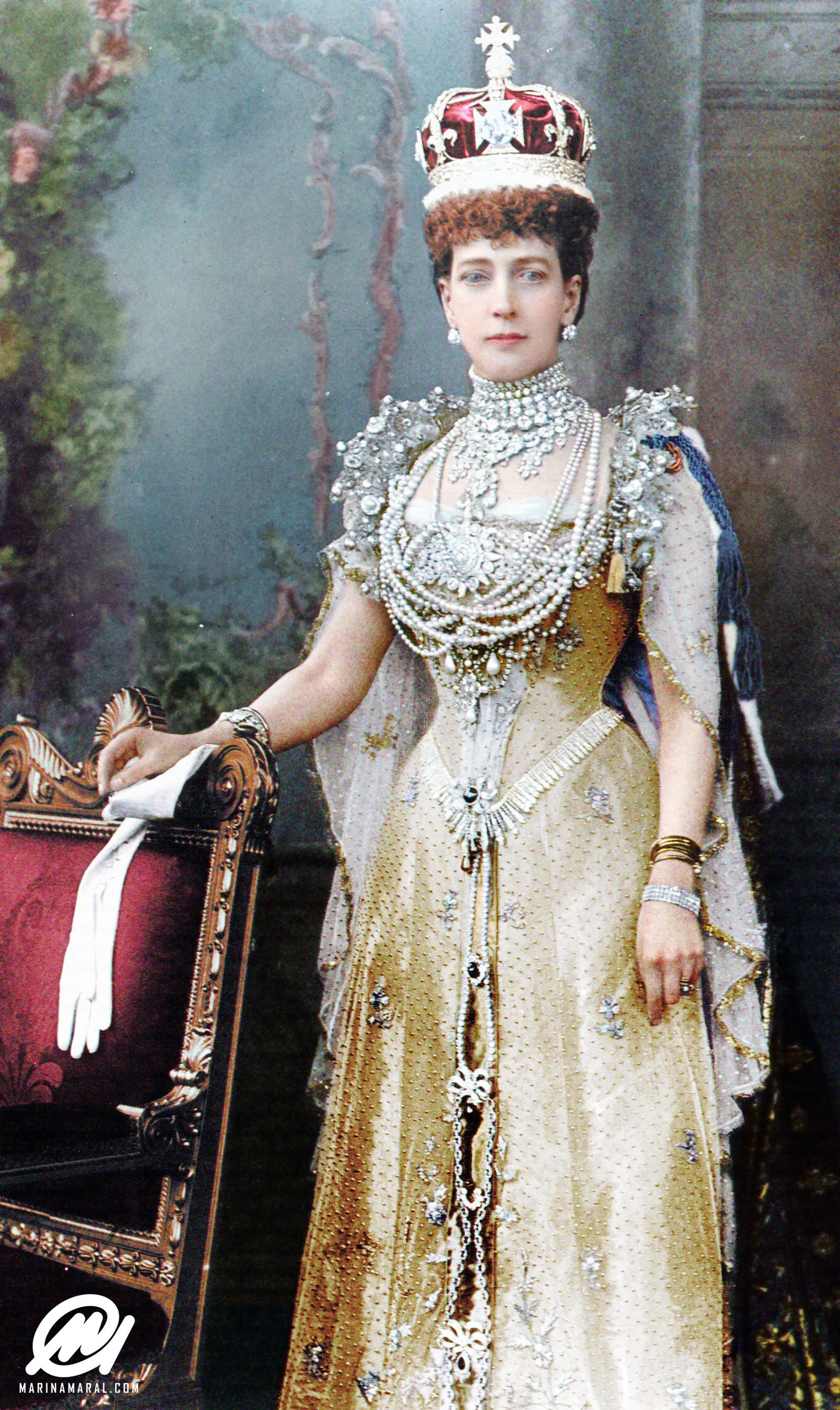

Queen Alexandra wearing the Dagmar cross (underneath those ropes of pearls) at...

The Dagmar Cross, 11th century. National Museum of Denmark.

So when King Frederick VII of Denmark's daughter Alexandra wed the Prince of Wales in 1863, it seemed only fitting that he gift her a copy of this ancient cross to take with her to England. But museum shop item this was not. King Frederik VII included a piece of silk from the grave of King Canute and a sliver of wood said to be from the True Cross inside the reliquary. Alexandra (who was not understated when it came to jewelry) went a step further and sent the pendant to the Danish court jeweler Julius Dideriksen who mounted it onto a necklace made from 118 pearls and 2,000 diamonds. He even included two giant pearls that had been exhibited at the Great Exhibition at the Crystal Palace in 1851. Queen Alexandra wore the necklace and cross at the coronation in 1902. There was such a demand for similar crosses that jewelers couldn't keep up.

Touch Wud

A well-worn "Touch wud" charm from the WW1 era. From the Erica...

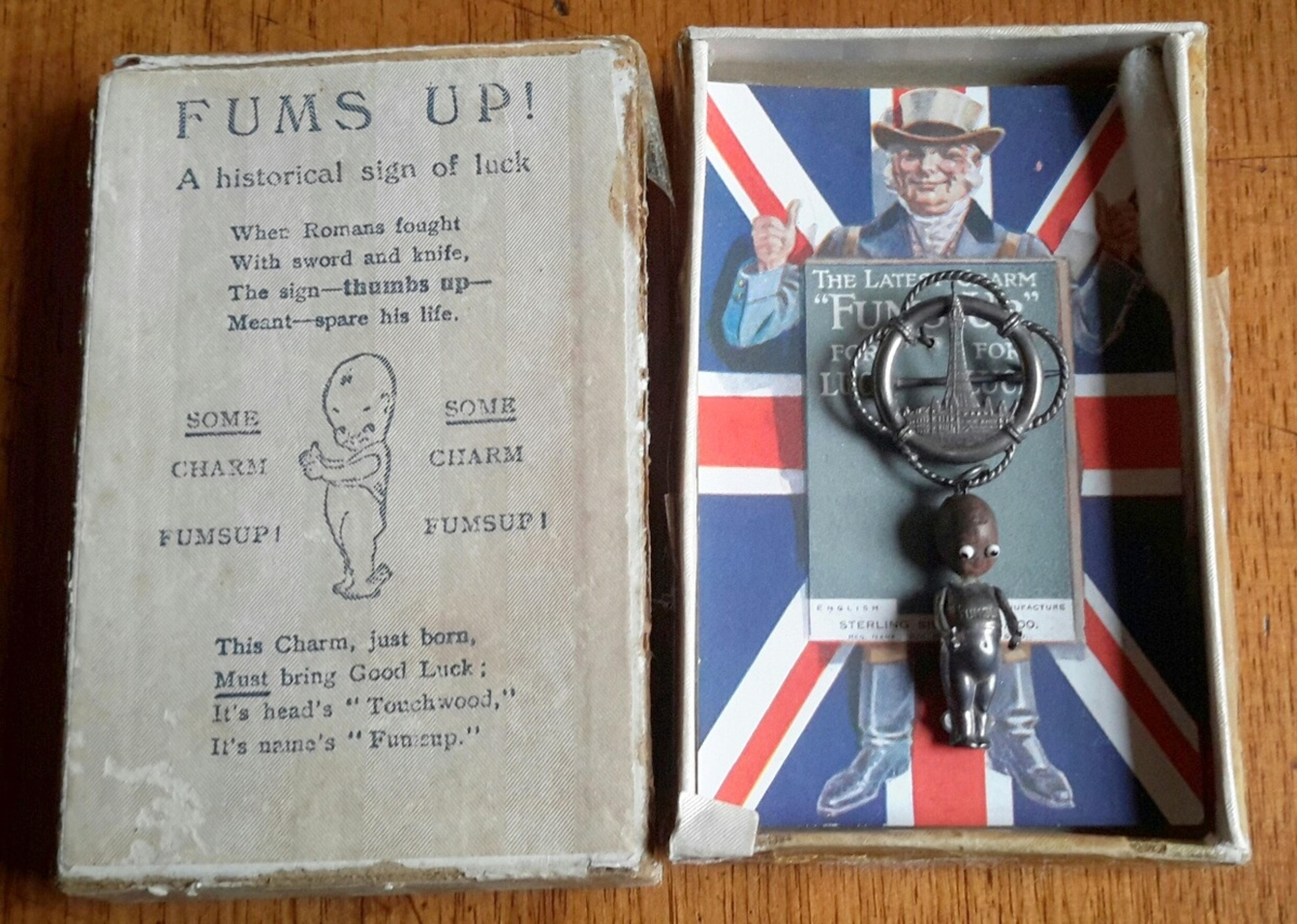

WW1 "Fumsup" in original packaging.

The superstitious phrase "touch wood" is spoken when one acknowledges some good fortune and wishes the good fortune to continue. It has many variations; In Pagan times, the trees were thought to be the homes of woodland spirits. Touching a tree would evoke the protection of the spirit within. ("Touch Wood" is the British counterpart to the American "knock on wood" which can be dated until at least the early 17th century. ) In an 18th century British children's game, touching a piece of wood would protect one from being tagged "out". In both instances, the idea is that the admission of good fortune may arouse jealousy of a mischievous spirit who will destroy that person's good luck.

In 1914, British entrepreneur Henry Brandon designed a good luck token for loved ones to give to soldiers heading off to World War I. They took the form of a "Touch Wud" charm that could be worn around the neck: a round little dude with silver limbs touching its own wooden head. Many surviving charms show evidence of frequent rubbing, indicating they were kept close on the body so the young WW1 soldier could avoid being "tagged" in warfare....forever.

Brandon also designed a second charm, call the "Fumsup" (thumbs up). This charm has thumbs raised and originally came with a little card with a classical reference: "Where Romans fought with sword and knife, the sign — thumbs up — meant spare his life." It's since been debunked as fiction, but in the 19th and early 20th centuries it was believed that ancient Roman emperors had the power to show mercy on Gladiators by giving a "thumbs up" in the arena. Maybe on the Western Front the same hand gesture could aid in survival? Any little bit of an advantage would help during a war that saw huge casualties.